You may have noticed over the past nine months of receiving this newsletter weekly (or whenever you subscribed) that I have only rarely reviewed any folk or fairy tales. This is because they are, without a doubt, my most revered category of children’s books — the most important books I read my own kids — and I never wanted to treat those titles as if they were like any other, because they’re not. I have Lots of Opinions about fairy tales.

In this issue you will find everything I want to say, plus the giant brain dump of reviews and recommendations I have come to offer when I write special editions or “Spotlight On”offerings. (This one became dense enough that I’ve split it into two parts — Part 2 will arrive next Wednesday, as usual.)

Let me begin by saying: I am not a scholar, nor am I some sort of expert on folk and fairy tales (though I do have a degree in English, have done ample analysis on all sorts of literature, and have managed to produce a fairly well-informed newsletter for you all these months now), but I have done my research. I’ve read extensively about the importance of fairy tales and undertaken my own field work from the comfort of my couch, underneath two warm little bodies, for nearly seven years now. I offer you what I know, along with my encouragement to read your children fairy tales — if you manage nothing else, no other kind of reading, this is enough.

There is good debate about whether or not Albert Einstein ever actually uttered his famous quote on this topic — “If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales” — but regardless of its veracity, the spirit of the sentiment is deep and true. (I personally believe that Einstein was the greatest scientist of the 20th century not because he was smarter, or a better mathematician, than others in his field but because he had an enormous imagination that made room for the possibilities of the universe.)

Bruno Bettelheim, an Austrian psychologist, scholar, public intellectual and author wrote an entire book — the book — on this topic. It’s a dense academic read that took me over a year to finish, so I will let Wikipedia do its job on this one and explain the gist of his premise:

“Bettelheim analyzed fairy tales in terms of Freudian psychology in The Uses of Enchantment (1976). He discussed the emotional and symbolic importance of fairy tales for children, including traditional tales at one time considered too dark, such as those collected and published by the Brothers Grimm. Bettelheim suggested that traditional fairy tales, with the darkness of abandonment, death, witches, and injuries, allowed children to grapple with their fears in remote, symbolic terms. If they could read and interpret these fairy tales in their own way, he believed, they would get a greater sense of meaning and purpose. Bettelheim thought that by engaging with these socially evolved stories, children would go through emotional growth that would better prepare them for their own futures.”

On page 155 of The Uses of Enchantment, Bettelheim writes, “The fairy story communicates to the child an intuitive, subconscious understanding of his own nature and of what his future may hold if he develops his positive potentials. He senses from fairy tales that to be a human being in this world of ours means having to accept difficult challenges, but also encountering wondrous adventures.” (emphasis mine)

He goes on: “Unfortunately, some moderns reject fairy tales because they apply to this literature standards which are totally inappropriate. If one takes these stories as descriptions of reality, then the tales are indeed outrageous in all respects — cruel, sadistic, and whatnot. But as symbols of psychological happenings or problems, these stories are quite true.”

He’s dead on. Fairy tales especially can be — often are — very dark and violent. Possibly you’re thinking, “I don’t want to read this to my kids!” I get it. I almost gave away Paul Galdone’s The Three Little Pigs when my first child was a toddler because I didn’t want to expose my little one to the blunt violence of the traditional ending (the wolf in a pot of boiling water, the end). But after reading Bettelheim and others who present fairy tales as important tools of and for emotional development, I revised my opinion. Now, along with many picture books that are sometimes retold in a way that changes their darkest aspects and sometimes stay true to every detail (this is why you don’t see picture books of some of the goriest tales, e.g., The Juniper Tree — who could bring themselves to illustrate the abuse, murder, and cannibalism of that story?), we often read straight from complete collections of Grimm. If there are questions about the wickedness or evil found therein, we talk about it; we do not skip it or shy away. Because this is the world, is it not? Darkness exists, both outside and inside us. I am vehement about protecting my children’s childhood; my husband and I carefully monitor what they are exposed to, their consumption of information — but I do not believe in shielding them from fairy tales, because they speak to the human condition, to truth, to justice, to the light as well as the dark, and how to come to terms with it all.

📚

Further points for our purposes here: what’s the difference between a folk tale and a fairy tale, and why bother making the distinction? Well, they are different, for one thing, though no one has ever been able to agree definitively on what those differences are (the debate has been raging for as long as there has been a debate to be had) but generally:

Folktales are an oral tradition with no author; scenarios happen in real life and not the world of magic or fantasy; characters are often (though not always) animals with human characteristics and/or the ability to talk; they were written for common folk with the intention of wide appeal.

Fairy tales are a written tradition with an author (though sometimes the author/s took their stories from the oral tradition); situations, events, aspects of the story are magical and/or supernatural; characters can be (though are not always) mythical or otherworldly; many (though not all) were originally written for the European aristocracy.

Of course, in contemporary times we are redefining the definition of fairy tales all the time — no one is arguing that a Caribbean Cinderella story was written for an 18th or 19th century French aristocrat; in fact, we know that the Cinderella story is one of the oldest and most widely told tales in the world, with thousands and thousands of variations found in all different cultures, the earliest written record from a Greek geographer somewhere around 7 BC—AD 23. So any conversation about “fairy tales” must first be an understanding that the very definition is a Euro-centric one. That in and of itself is one reason I wanted to write this issue — because I wanted to offer many non-European versions of tales we tend to automatically assume had their genesis in Europe.

It’s also important to recognize the age of folk and fairy tales — by which I mean, even the most ancient of these stories full of deep human truths have picked up social and societal baggage along the way. The nonprofit organization, SocialJusticeBooks.org goes further and says it so well:

“Folk and fairy tales have long been a mainstay of children’s literature. In the cultures from which they come, folk and fairy tales were used to teach important lessons and values related to their culture of origin. Children love them in their original versions — not their commercially sanitized adaptations. However, folk and fairy tales also carry messages that convey sexism, classism, and racism and must be used thoughtfully as part of introducing young children to diversity and anti-bias values of quality and fairness.”

Does this mean we shouldn’t read folk and fairy tales? Of course not. But it does mean, like anything else we share with children, that we must look at those stories through a critical lens and plan our approach. If there is a problematic content — and there absolutely will be — how will you handle it, and what will you do to balance it?

An example of this in my own family’s reading life is confronting the near-constant gender issues (almost entirely female gender issues, including but not limited to roles, stereotypes, discrimination, etc.) and sexism that come up in many fairy tales. We discuss. We read a wide variety of stories that expand the notions of “what men do, who men are” and “what women do, who women are” (which still takes some effort despite the fact that this is 2021). And outside of the narrow category of this genre, we read a vast number of books with narratives featuring empowered women (girl power, in my personal definition, being broad, inclusive, and intersectional) as well as authentically whole men (the latter of which is far more difficult to track down, because we have a long way to go when it comes to recognizing and honoring men in their real emotional complexity). This is merely a case in point — this approach can be applied to any content, any bias you encounter in folk or fairy tales. They’re important enough on variety of levels to do the work of separating the baby from the bathwater.

A few final notes before we jump in:

Attribution: it’s all over the place when it comes to folk and fairy tales. E.g., a book will be “by the Brothers Grimm and Some Author,” or “retold by Some Author” or merely “by Some Author.” Because of their inherently mutable nature and because at some point or another these were tales all told by someone other than the person who wrote them down (the Brothers Grimm didn’t write their fairy tales as original stories but merely collected them from fellow Germans willing to sit down and share them; Charles Perrault mostly wrote his own — though he intentionally made it seem like they came from the common people of late-17th century France — and Hans Christian Anderson wrote all of his own, 156 of them), I’m not going to try to parse out who originally committed them to paper, but use whatever is written on the cover of the book or listed online. (That said, if you cannot find some of these titles, try searching using the multiple authors.)

Additionally: I consider nursery rhymes, fables, tall tales, pourquoi/etiological tales (a story that explains why something is the way it is), stories from ballets/operas, and myths and legends different categories than folk and fairy tales (though there is absolutely overlap, I have to draw lines somewhere to keep this manageable), so I’ll not be including any of those here. And, since there are literally thousands of versions of folk and fairy tales out in the world, no list can possibly be exhaustive: included here (and in Part 2 coming next week) are only titles that I have actually had in my own hands and read to my children. I have included cultural variations (Cinderella belongs to no single culture, as I said) but left out all but the most faithful alternative tellings and parodies, because I strongly believe kids should know the original story before encountering any kind of spin (that’s the only way the spin makes sense). Lastly, since some of the stories I am reviewing are extremely well-known and others not so much, I began each with a tiny plot summary before expounding on what I consider the specific title’s virtues.

OKAY! 👏 Finally. Here we go.

The Rough-Face Girl by Rafe Martin, illustrated by David Shannon (1992)

We have read many versions of Cinderella — there are a lot of them out there, and a ton of good ones (I’ll share a list of recommended Cinderella titles next week in Part 2) — so it’s a hard category in which to rise to the top, but The Rough-Face Girl does it. Set on the shores of Lake Ontario, this Algonquin version opens with “a very great, rich, powerful, and supposedly handsome Invisible Being” — a being unknown and unseen to all but his sister — whom all the women want to marry. There are two petty, vain older sisters who demand jewelry and new clothes from their father in order to impress and win the heart of the Invisible Being, and a kind, abused younger sister who asks her father for whatever he can give. Of course, we all know how the story ends, and this version is no different than all the others in that aspect of the plot — what sets this title apart is the Invisible Being himself (no spoilers here, I will merely say that he is not the traditional Prince Charming we are familiar with; in my opinion, he’s better in every way). Martin has written a tender, truly lovely story, matched perfectly by Shannon’s haunting illustrations. Of all the Cinderella titles we own, this one is the most beloved and most revisited, and I know why: it’s stunning, and deserving of the attention.

The Twelve Dancing Princesses by the Brothers Grimm, illustrated by Dorothée Duntze (2013)

Once there was a king whose 12 daughters awoke every morning exhausted, with mysteriously ruined shoes. Befuddled, the king puts out a call to anyone who can figure out what happens every night — the one who solves the mystery will get his choice of princess to marry and inherit the kingdom. Many come and fail, until one man arrives with an invisibility cloak (it’s not Harry Potter who wins the day here, merely the tool J.K. Rowling made use of) and discovers that the princesses descend underground, dance themselves senseless at a great ball, and return spent in the morning. For whatever reason, the story of the twelve dancing princesses — known in Grimm’s original as “The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces” — has been one of our favorites, and we’ve read many versions. This one has been altered the least, preserving the whole plot and sentiment of the story if not the exact language that Jacob and Wilhelm used, and benefits enormously from Duntze’s skillful, perfectly strange illustrations. Our favorite scene is the moment when the princesses depart in the night on their boats — Duntze depicts the boats themselves as giant high heels, a visual choice that brings endless delight when we revisit that page again and again. This is a well-told tale, supremely well done, and I think the best of all the variations.

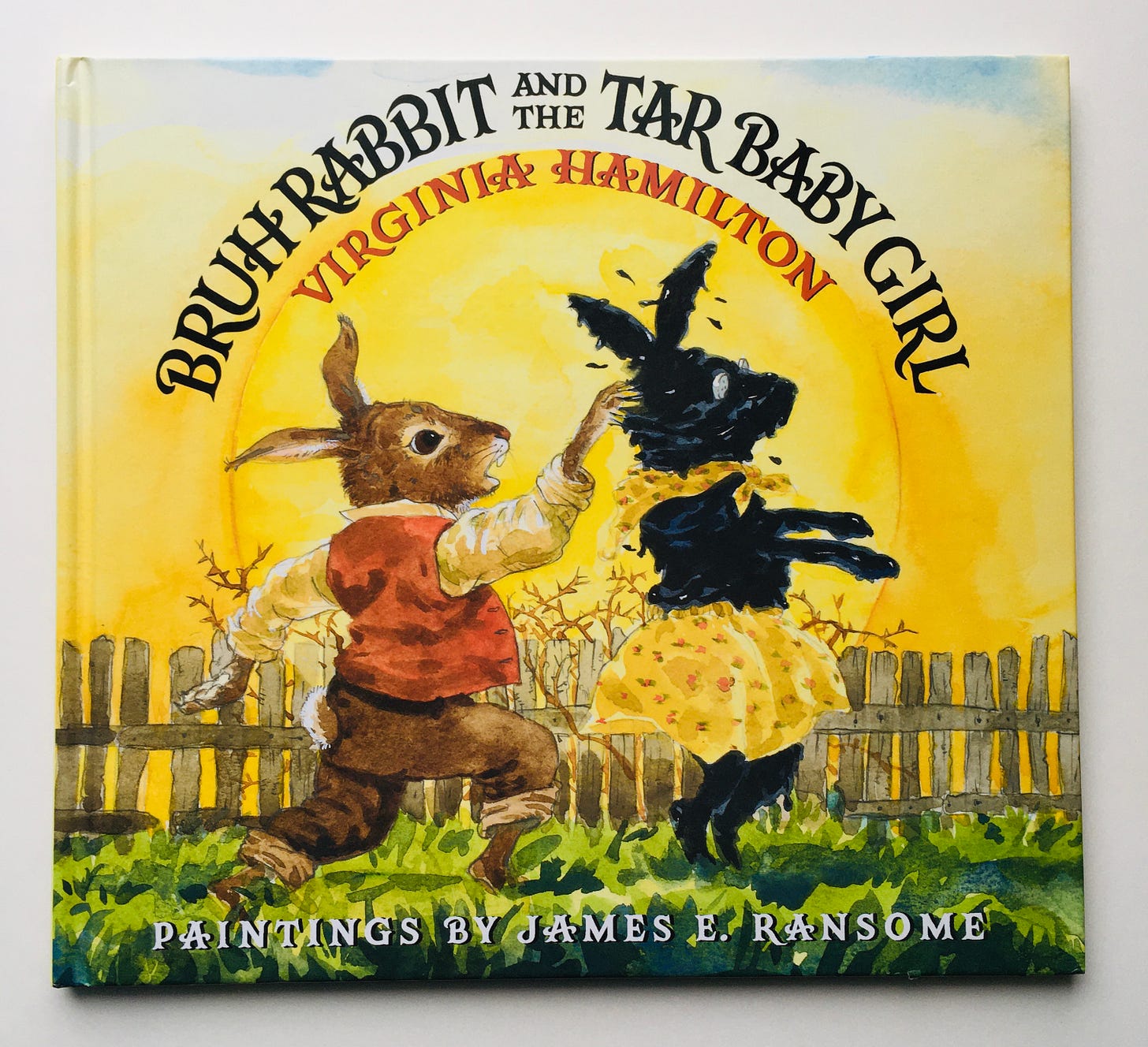

Bruh Rabbit and the Tar Baby Girl by Virginia Hamilton, illustrated by James E. Ransome (2003)

The only book my husband — who grew up in a place literally on the Mason-Dixon line — has ever asked me to obtain for him was a collection of Brer Rabbit stories. That classic trickster’s many escapades formed the bulk of the stories his own father told him at bedtime, and he wanted to be able to do the same with our kids. (Of course I immediately procured several collections — two of which I recommend in my list of Collections below — and the few stand-alone titles I could find, this being the errand I’ve been waiting to be sent on for basically the entire 16 years we’ve been together.) Aside from this personal motivation, and apart from their being hilarious and entertaining to children (which is, alone, enough reason to read them), familiarity with, or at least some knowledge of Brer Rabbit tales is part of being a culturally literate American. (There is a lot of fascinating information about Brer Rabbit and Uncle Remus tales online, not least a tidbit from Wikipedia that states, “In a detailed study of the sources of Joel Chandler Harris's ‘Uncle Remus’ stories, [scholar] Florence Baer identified 140 stories with African origins, 27 stories with European origins, and 5 stories with Native American origins.” These are the things I geek out on.) And if that’s all not reason enough: I personally don’t want my children exposed to solely Euro-centric folk and fairy tales. As I’ve written before, representation matters — diversity and inclusivity applies to cultural heritage as much as anything else — and at least in this category of children’s books, it’s not terribly hard to counterbalance the dominant culture. There are no princesses waiting to be rescued in Brer Rabbit, and it’s pretty damn refreshing.

I am hard-pressed to think of an author who has done more to bring a significant body of Black folklore to the world of children’s literature than the late Virginia Hamilton. Her 41 books — including the spectacular collections, Her Stories: African American Folktales, Fairy Tales, and True Tales and The People Could Fly: Black American Folktales, both of which I also recommend in my list of Collections below — all have a deep focus on tradition, memory, and what’s passed down from generation to generation, especially in the lives and families of African Americans.

It makes sense, then, that her version of a Brer Rabbit (aka Bruh Rabbit, B’rabby, or Buh Rabbit) tale — an oral tradition passed down by African Americans in the Southern U.S. — is so good: this title was published posthumously, after she’d had decades to perfect her craft. In this story, “It was a far time ago, and before a first winter snow, that Bruh Wolf had a run-in with pesty Bruh Rabbit.” Bruh Wolf had planted corn and peanuts one year, and of course, Bruh Rabbit had not — but that didn’t stop the trickster bunny from trying to help himself to Wolf’s crop. In an effort to stop this thievery, Bruh Wolf puts up a “scarey-crow,” to no avail, and eventually lands on the idea of a tar baby girl — a human-sized rabbit covered in tar. If you’re familiar with Brer Rabbit’s wily personality and many of his antics you might be able to guess what happens, but if not, you’ll have to read this for yourself. Full of colloquial language and phrasing (“dayclean” for dawn, “daylean” for dusk, “croker sack” for a burlap bag), this is not only fun to read aloud, but fun to look at — Ransome’s paintings are colorful works of art that add much to the action (when Brer Rabbit jumps on the tar baby girl’s back, the expression on his face says it all). This is the perfect title for preschoolers all the way through upper elementary — anyone who appreciate a lively and energetic read.

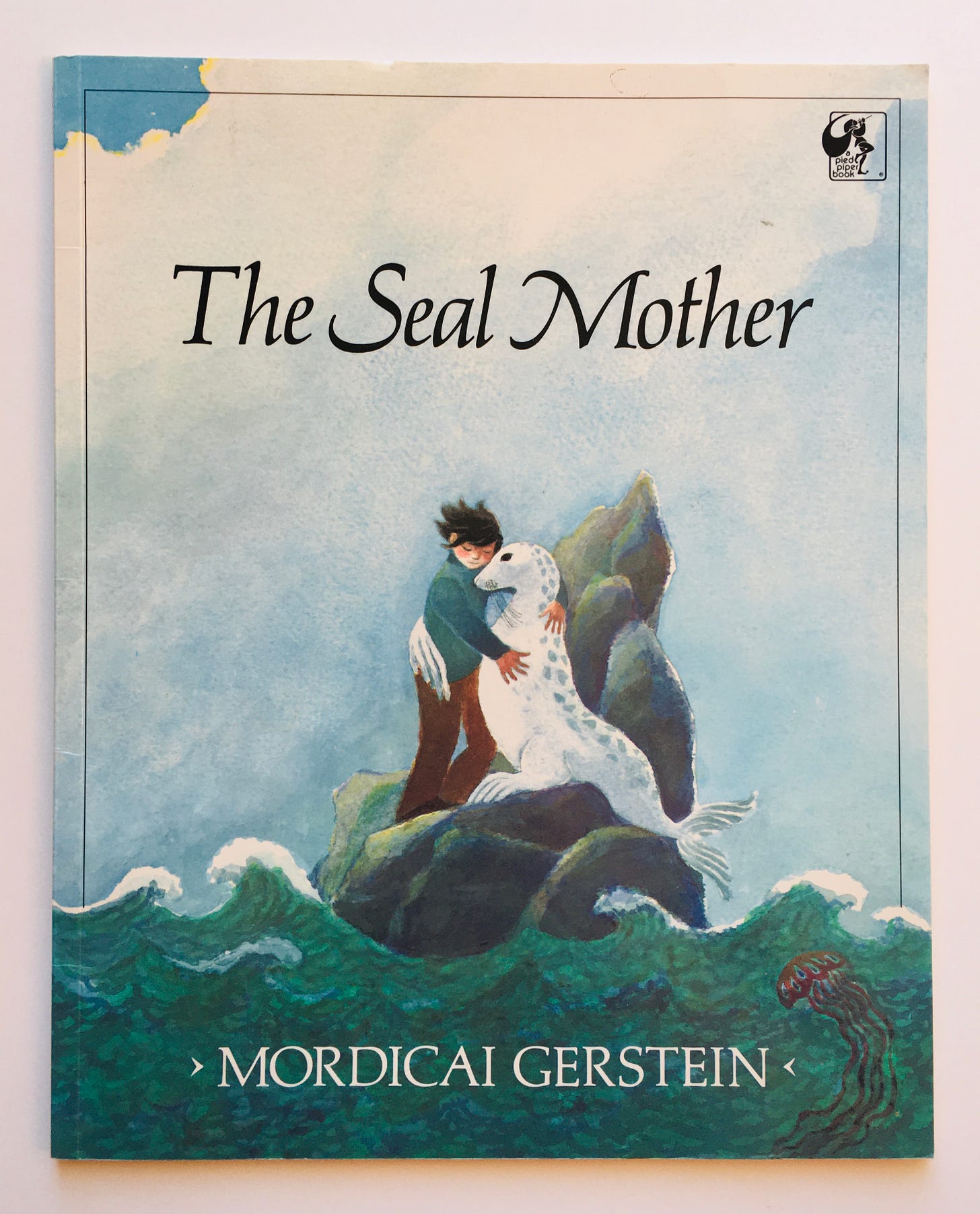

The Seal Mother by Mordicai Gerstein (1986)

Selkie stories are folktales from the Northern Isles and Western coast of Scotland, sometimes including Ireland, and always center around the same motif: a seal comes out of the water, takes off its skin, and transforms into a woman who is then tricked into a relationship with a man, who prevents her from returning to the sea for a certain period of time by hiding her skin. Sometimes she is able to return, sometimes not, but the shedding of the sealskin to become a woman and subsequent entanglement in some mortal drama is key. This title tells a very traditional version of this type of story — only here, after the coercion, the selkie has a baby with the man who deceived her and stole her skin. His whole life the boy knows something is a bit strange about his mother, and one day, she disappears. When the boy goes to look for her he discovers her secret along with a whole family that lives beneath the waves. Unlike many modern retellings of folk and fairy tales, this one’s ending is possibly happy, possibly sad, depending on which way you look at it: the boy loses his mother, yes, but she returns to the sea where she belongs and his family greatly expands. Gerstein’s prose and soft paintings work in tandem to tell this riveting, mournful tale with an air of compassion that feels a bit rare in the genre — there’s an uncommon softness here, and it’s just right. I can’t think of a better way to handle a story that asks the deep and timeless question: how much do we lose when we love someone?

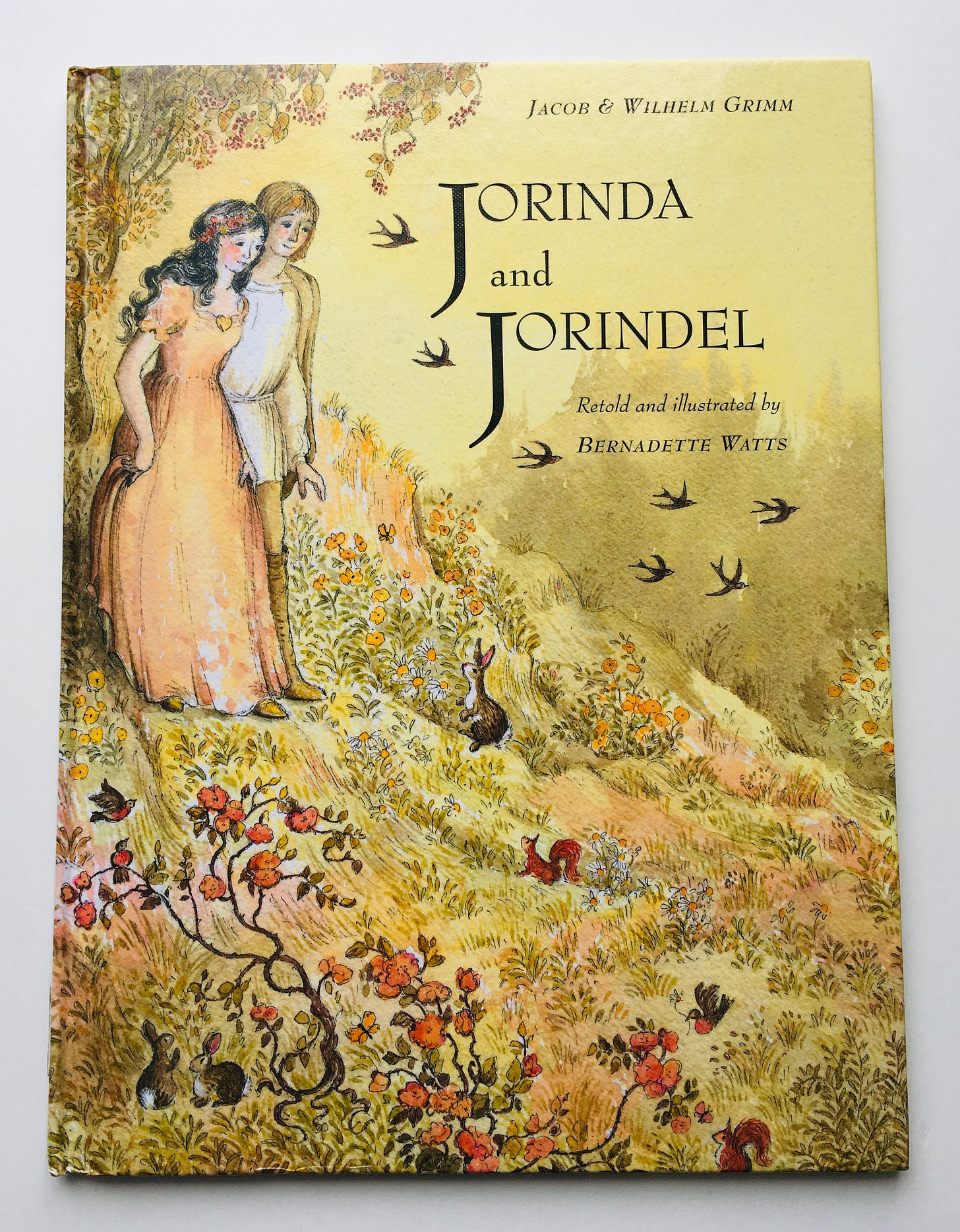

Jorinda and Joringel by Bernadette Watts (2005)

One of my great joys of being a mother has not only been sharing beloved books with my children, but discovering new ones to love alongside them. This is exactly what happened with the story of Jorinda and Joringel — I’d never before heard (or at least never remembered hearing) this tale. A witch lives in a castle deep in the forest, and her pastime is turning young women into birds and keeping them in thousands of cages in her lair (an interesting hobby, to say the least). Any young man who gets too near her castle is turned to stone. Despite knowing of the witch and her proclivities, one day Jorinda and Joringel, a young couple in love, find themselves too near the castle and end up in the exact situation they were trying to avoid: Jorinda is now a nightingale. The witch, for reasons of her own, frees Joringel, but he is without hope of helping his love until one night the solution comes to him in a dream: he must find a particular flower with a pearl inside, and with its magic, reverse the witch’s spell. He finds the flower, storms the castle, and despite the witch’s best efforts, manages not only to free Jorinda but the many other birds in cages as well (though it’s not stated in this title, the number of cages is often cited as 7,000, which freaks me right out every time). Watts’ talent, in my opinion, lies in her willingness to take on many lesser-known fairy tales (I’ll be covering another one next week), and to render them simple enough — though not watered down in the least — for picture books. It’s in this way that, well before we started reading straight from much more challenging collections of Grimms’, my children became acquainted with many Grimms’ stories. Watts’ style, in both writing and illustration, is always warm and accessible, making her my top pick for fairy tale titles for toddlers, preschoolers, and early elementary kids.

Note: this was republished by Floris Books in 2017 as The Enchanted Nightingale: The Classic Grimm’s Tale of Jorinda and Joringel; it is the same book

Also highly recommended (both folk and fairy tales)

Jack and the Beanstalk retold by John Cech

The Emperor’s New Clothes by Hans Christian Anderson, illustrated by Nadine Bernard Westcott (this is a fun, comic title that nonetheless stays true to the original story in every way)

The Princess and the Pea by Hans Christian Anderson, illustrated by Dorothée Duntze

Little Brother and Little Sister by Barbara Cooney (this is our favorite fairy tale title, bar none, but it’s MIA somewhere in our house — no doubt squirreled away out of love — and for the life of me I wasn’t able to find it to photograph and review)

The Three Bears by Paul Galdone

The Three Little Pigs by Paul Galdone

Rapunzel by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, illustrated by Maja Dusíková

Rapunzel by Rachel Isadora

The Elves and the Shoemaker by Jim LaMarch

The Little Red Hen by Diane Muldrow (a great baby shower title)

East O’ the Sun and West O’ the Moon by P.J. Lynch

Stone Soup by Ann McGovern

Puss in Boots by Charles Perrault, illustrated by Fred Marcellino

Sleeping Beauty by Cynthia Rylant (this is published by Disney Hyperion so it has some Disney-ish qualities, but Rylant applied the full force of her not-insignificant writing talent here, and it’s very good)

Tasty Baby Belly Buttons by Judy Sierra (I reviewed this in issue No. 7)

The Talking Eggs by Robert D. Souci

The Tale of the Firebird by Gennady Spirin

Sugar Cane: A Caribbean Rapunzel by Patricia Storace

Joseph Had a Little Overcoat by Simms Taback (one of my all-time top picks for toddlers and preschoolers)

The Star Child by Bernadette Watts

Tam Lin by Jane Yolen

Rumpelstiltskin retold by Paul O. Zelinsky

Folk tales:

The Gingerbread Man by Jim Aylesworth

Goldilocks and the Three Bears by Jan Brett

Town Mouse, Country Mouse by Jan Brett

A Big Quiet House: A Yiddish Folktale from Eastern Europe by Heather Forest

Stone Soup by Heather Forest

The Three Billy Goats Gruff by Thea Kilros and Raina Moore (this is a great baby shower title)

The Rainbabies by Laura Krauss Melmed (I reviewed this one in issue No. 17)

The Snow Child by Freya Littledale (I reviewed this one in my special edition on winter)

The Little Red Fort by Brenda Maier (I reviewed this one in issue No. 10)

Stone Soup by Jon J. Muth

The Lion & The Mouse by Jerry Pinkney (wordless)

The Gingerbread Man by Bonnie and Bill Rutherford

Sukey and the Mermaid by Robert D. San Souci

Two of Everything: A Chinese Folktale by Lily Toy Hong (also great as a living math book)

The Lion and the Mouse by Bernadette Watts

It Could Always Be Worse: A Yiddish Folk Tale by Margot Zemach

Collections:

Without a doubt our favorite fairy tale collection is Grimms’ Fairy Tales, translated by E.V. Lucas, Lucy Crane, and Marian Edwards, illustrated by Fritz Kredel, published by Grosset & Dunlap, Inc. in 1945. (Grosset & Dunlap also published a collection of Hans Christian Anderson that matches Grimms’ for a nice little set.) This title is long out of print but readily available, cheap, on the used market. I highly recommend it. It’s not the complete Grimms’, but it’s varied enough to go beyond the well-known selection offered in titles with fewer tales. Nothing has surprised me more than how much my children love this specific book, which proves to me everything that Bruno Bettelheim believed is true — the original stories don’t need to be filtered, softened, or modernized; in fact, it’s better if they are not.

Native American Animal Stories by Joseph Bruchac

An Illustrated Treasury of Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Anderson, illustrated by Anastasiya Archipova

The Faber Book of Favourite Fairy Tales edited by Sara and Stephen Corrin (I received this book when it was published in 1988 — I’ve kept it, of course, and their version of “Bluebeard” haunts me to this day)

The Classic Tales of Brer Rabbit by Joel Chandler Harris, illustrated by Don Daily

The Adventures of Brer Rabbit and Friends by Joel Chandler Harris, illustrated by Eric Copeland (this title and the previous one feature different stories and are both excellent)

An Illustrated Treasury of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, illustrated by Daniela Drescher

Her Stories: African American Folktales, Fairy Tales, and True Tales by Virginia Hamilton

The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales by Virginia Hamilton (some editions include a cd/audio, which is excellent)

The Faber Book of Nursery Stories edited by Barbara Ireson

Any of Andrew Lang’s “coloured fairy books” (there are 25 of them, all named a different color), but to start with: The Blue Fairy Book or The Red Fairy Book

Uncle Remus: The Complete Tales by Julius Lester

Moon Cakes to Maize: Delicious World Folktales by Norma J. Livo (a fun international collection centered around food)

Magical Tales from Many Lands by Margaret Mayo

The Helen Oxenbury Nursery Collection by Helen Oxenbury (includes nursery rhymes — this is my most recommended title to get the littlest littles started on fairy tales, around 2yo)

The Complete Grimm's Fairy Tales published by Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library (the complete Grimm’s is extremely dark so you may want to preview for children younger than middle school)

Tatterhood and Other Tales edited by Ethel Johnston Phelps and its follow-up, The Maid of the North: Feminist Folktales from Around the World

The Provensen Book of Fairy Tales by Alice and Martin Provensen

The Juniper Tree: And Other Tales from Grimm, translated by Lore Segal and Randall Jarrell (this a particularly well-done and accessible translation but contains some of the darkest Grimm’s tales so again, you may want to preview)

Favorite Folktales From Around the World by Jane Yolen (this is an outstanding, widely varied international collection)

What are some of your favorite folk and fairy tale titles? Hit reply to let me know and I’ll include your responses in Part 2 next week (which will also include lists about Cinderella, as mentioned above, everything I haven’t already recommended, and a special note about our favorite fairy tale audio).

Lastly, I’ve put together a list on my Bookshop.org storefront called Folk and Fairy Tales, if you’re looking for pick up some new titles.

Thanks for reading, thanks for being here, as always. I appreciate you.

I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you make a purchase through my storefront.

I’m very interested in this list. We live in Michigan and I’ve discovered a great collection of Midwest folk tales by Native American legends by Sleeping Bear Press. One of those is always in my library stack each week.

I love fairy tales and can’t wait to look through all of your recommendations. My first exposure to fairy tales was a book my mother bought for me at my elementary school’s Scholastic Book Fair, which I still have - a hardcover copy of Grimm’s fairy tales illustrated by Arthur Rackham. She also gave me a book of Russian fairy tales edited by Jackie Onassis; the illustrations are gorgeous. Both still hold a special place in my heart, and I love looking back as an adult and realizing how big a role my mom played in my reading life.