Can we read? No. 31

I had to look at a calendar last week to remember the exact date I stopped going into the office, my then-kindergartener never saw her teacher in person again, and our daycare closed. A dubious anniversary if there ever was one. Meanwhile, here we are. And I’m not saying I’m ungrateful — we’ve been very, very lucky, and good things have grown from this muck. At the same time, feelings are complex:

Let’s keep going, okay? One day at a time. I will if you will.

👣

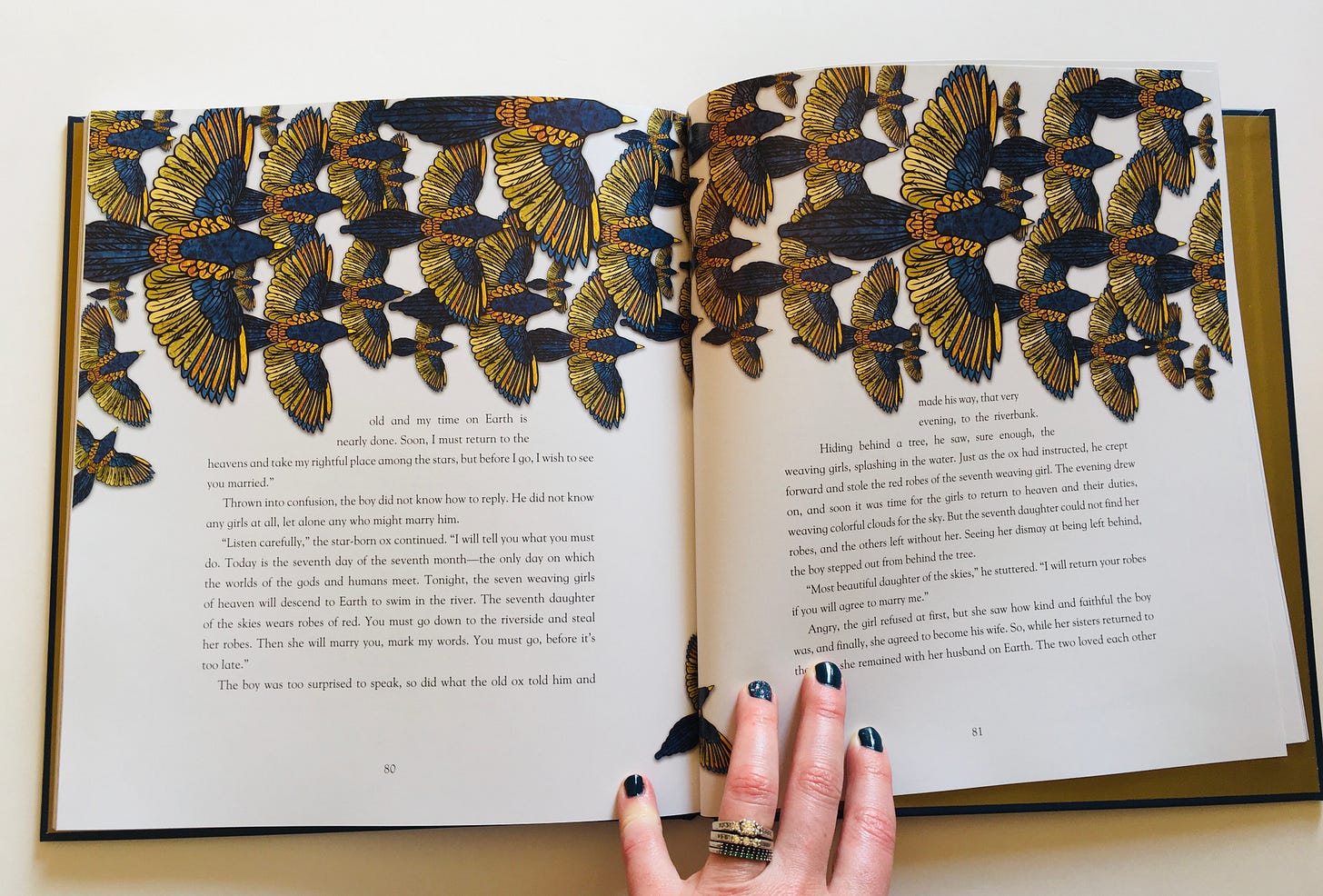

It seems I can’t go anywhere without seeking out books. When I was up north for my long weekend I made it to a Goodwill in the middle of the state (I found six new titles for my holiday/seasonal boxes, as if I need any new titles for my holiday/seasonal boxes) as well as an independent bookshop (I don’t often buy new books but when I do, I try to put my money where my mouth is and support the small local stores that are keeping places weird out there). I picked up three books I just couldn’t walk away from: Come All You Little Persons by John Agard, which has text and illustrations that are pure magic; The Stars by H.A. Rey, which I’ve been meaning to buy forever; and Star Stories: Constellation Tales From Around the World by Anita Ganeri. Both my kids are super into stargazing and learning constellations right now, and I want to be able to offer them a broader range of stories than those from the Greeks alone — I liked this title for that reason along with the illustrations, which made me think this is what might occur if some Egyptian hieroglyphics, a Tlingit carving, and a Tiffany lamp got together and had a baby:

I love finding treasures. Aside from their being my singular obsession in life, it’s pretty much the reason I keep buying books.

Here’s to finding some treasure this week 💎 even if it’s small.

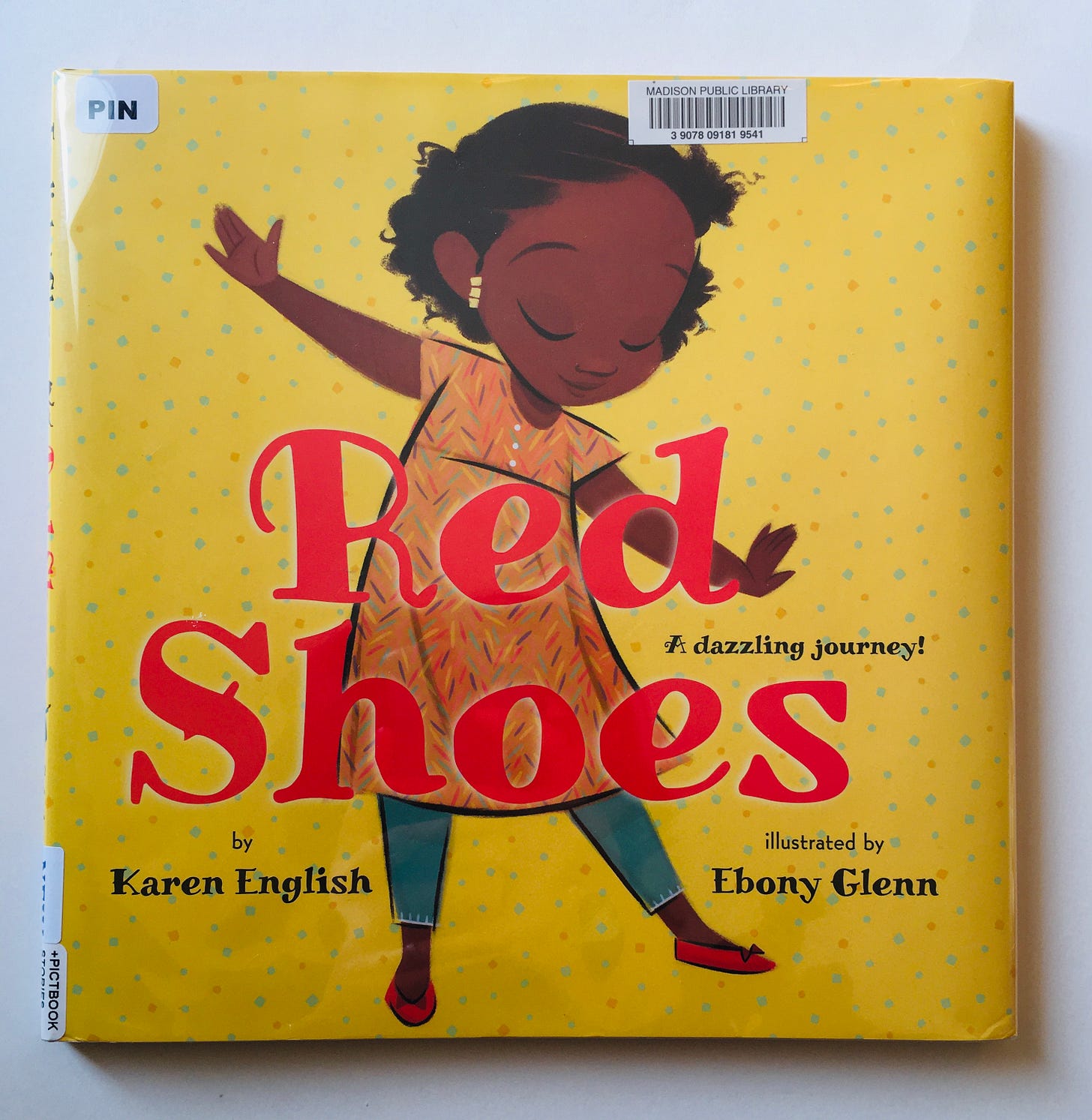

Red Shoes by Karen English, illustrated by Ebony Glenn (2020)

We’re still working our way through all things Ebony Glenn, and why not? As I’ve mentioned in reviews of two other titles she has illustrated (in issues No. 20 and No. 21) her work is bright, cheerful, and just the kind of upbeat we need here in March, where we are experiencing our annual false spring (we’ll have at least one more snowstorm before winter is actually over but somehow we forget that every single year). Red Shoes is the touching story of a little girl, Malika, who falls in love with a pair of red shoes she sees in a shop window. Her Nana buys them for her as a surprise and Malika is delighted — the reader follows Malika and her shoes through many moments of life, from rain on the first day of school, to dancing on Daddy’s feet, to kicking cousin Jamal under the dinner table, to stomping away when she and her best friend Keisha have a fight. Eventually the shoes are too tight for Malika, and “she says goodbye to her wonderful red shoes,” just in time for Inna Ziya to see them in the window of the secondhand shop and snap them up. The red shoes are now bound for Africa, to another little girl, this one named Amina, “who fasted half the month of Ramadan,” and “deserves a special gift.” Glenn’s illustrations are enough to carry prose and a plot of much lesser quality, but this book thankfully suffers from neither: English has written a story so lovely it snuck up on me. Here, in the journey of a simple pair of shoes, we not only see different situations, different privileges, different values, different cultures, but also the same simple desires and needs, the same small pleasures — the places where our experiences diverge and the places they overlap, and the feelings we share. It’s beautiful and beautifully done.

Double Trouble for Anna Hibiscus! by Atinuke, illustrated by Lauren Tobia (2015)

In my Spotlight On: Counting Books last July I mentioned how fantastic Atinuke is (I was talking about Baby Goes to Market, which we still read frequently) and how much we adore Anna Hibiscus, especially on audio (Mutiyat Ade-Salu absolutely kills it narrating the Anna Hibiscus series, which remains my single favorite audiobook for children). So when I discovered that there’s an Anna Hibiscus picture book a few years ago, well, we started checking it out of the library every few months and haven’t stopped since. It’s the story of the birth of Anna’s twin brothers, the change that brings to her life, and how she feels about it all (it’s her idea to call one twin “Double” and the other “Trouble,” if that gives you any idea as to how she takes this turn of events). Like all the Anna Hibiscus books, the best part is the role of her large, warm family, and the things she’s upset about here reflect that: she is angry that her uncle, who makes her obi for breakfast every day, is too busy to do it; she is frustrated that her grandmother, whom she eats with every morning, is still sleeping because she was up all night helping with the birth, etc. And yet, even though this all takes place in Anna’s “amazing Africa,” in a compound we’re able to view for the first time through Tobia’s vibrant and lively illustrations, full of an extended family the likes of which we would virtually never see living together in the U.S., there is so much here to connect with: the way Anna is cared for; the way she and her mom reconnect after a long day; the way she moves through her complex feelings, which are utterly relatable, after all. My favorite spread is one where her father holds her while she screams her heart out — the tenderness, acceptance, and unconditional love of that moment says everything you need to know about not just this title but all of the Anna Hibiscus books. They are, quite simply, wonderful.

Most Beloved Sister by Astrid Lindgren, illustrated by Hans Arnold (2002)

I am, in fact, writing about another Astrid Lindgren book (I told you I’m in the middle of an obsession) but I really and truly recommend it, so does it matter? Originally published as part of a short story collection in 1949, then as a stand-alone edition in 1979, it wasn’t translated and published in English until 2002, so the pub date is a little misleading, but regardless: like all of Lindgren’s tales, this one is satisfying, deeply weird, and really fantastic. On the surface it’s the story of a little girl — Barbara, who has a “secret friend” that lives in a hole beneath a rose bush in the garden. This friend is Barbara’s twin sister, Lalla-Lee (in the running for my favorite name ever, I think), with whom Barbara has the most remarkable adventures — they play with their little dogs, Ruff and Duff; they feed their rabbits; they ride their metallic horses, Goldfoot and Silverfoot through the forest where they run away from ominous creatures called the Frights and are helped by cheerful, chubby little people called the Kind Ones (all illustrated beautifully by Arnold). All this would be riveting enough except when you look just a little closer at what’s really happening — the whole story hinges on two lines on the second page that are very easy to miss: “Papa likes Mama best, and Mama likes my little brother, who was born in the spring, best. But Lalla-Lee just likes me.” Underneath its mystical exterior this is the story of a little girl grieving the major change in the makeup of her family (not unlike Anna Hibiscus, really) enduring a loneliness she can only acknowledge and address through the solace and support of a “sister” of her own making. (I will spoil the end — though not fully — by telling you that Lalla-Lee does not last, but Barbara finds another way, a real way, to get what she needs.) Once I realized the subtext here I understood immediately why my 6yo — who is rarely still for even a moment — sat unmoving as we read this, utterly transfixed (she experienced this loss of family as a three-some once upon a time, too, of course). The enchantment of this story is undeniable — it’s pure magic and can stand on that alone — but it also touches something incredibly deep, not just in children but in humans. We all know what it’s like to feel heartbroken and alone — in this fantastical universe, Barbara’s life is rich and meaningful, she is seen and loved. As we all deserve to be.

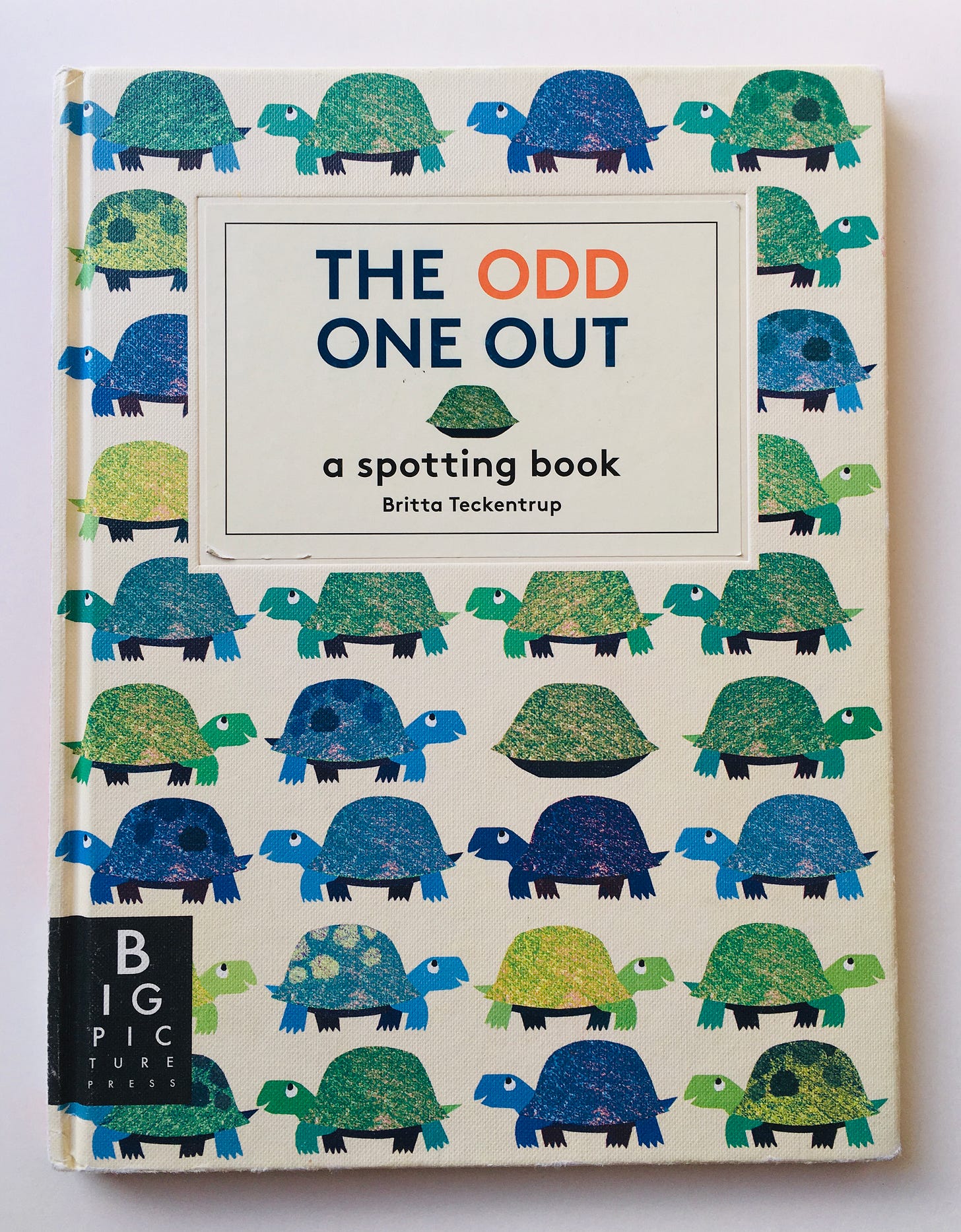

The Odd One Out: A Spotting Book by Britta Teckentrup (2014)

We love seek-and-find books in our house. Beyond Brer Rabbit collections and making up stories together after lights-out (featuring many characters lifted from 1980s cartoons, most notably Skeletor), they are my husband’s go-to bedtime reading. There are many seek-and-finds out there — the Waldo empire, of course, as well as the I Spy franchise, which I appreciate for their wide variety of titles and use of real photos, which gives them the feel of peeking inside a cabinet of curiosities no matter the topic — but I’d like to call your attention to those of Britta Teckentrup. Teckentrup is a German illustrator with an absolutely enormous oeuvre (she has written and illustrated over 100 books), and about as many awards for that work. Her style is colorful and exceedingly modern — many, if not all, of her titles have the feel of a graphic designer who has applied her prodigious skills to children’s literature. The fact that her images seem to take precedence over her prose perhaps proves this — but more to the point, it makes her handful of seek-and-finds unique, quite good, and on another level than most of the ones out there. The Odd One Out asks readers, through short rhyming text, to find, well, the odd animal or item out in every picture.

You may be asking: do seek-and-finds “count?” Are they really “reading,” much less reading aloud? The simple answer is yes, absolutely. Seek-and-finds, along with illustrations in all kinds of regular picture books, play a role in developing visual literacy — that is, interpreting and constructing meaning from visual images. I offer this from the eighth edition of Jim Trelease’s Read-Aloud Handbook edited and revised by Cyndi Giorgis (considered to be the absolute bible of reading aloud — I reviewed it in issue No. 12):

Why is visual literacy important? At home and school, our focus is usually on verbal literacy skills as we expand children’s vocabulary and enhance their ability to communicate. As adults, we have spent years accumulating vocabulary to express ourselves. We may avoid slowing down to talk about illustrations in picture books because we don’t possess the same level of confidence in our vocabulary to talk about art… Today, with the number of symbols, infographics, maps, charts, and other visual communication kids experience, it is vital for them to be able to interpret, negotiate, and make meaning from what they are seeing. This also includes illustrations they encounter in books. What better way to acquire and strengthen visual literacy skills than through pictures and conversation!

Well said.

Finding Wonders: Three Girls Who Changed Science by Jeannine Atkins (2016)

If novels-in-verse are having a moment — er, more like a decade, and they are — then I am here for it. This title from Jeannine Atkins focuses on the lives and careers of three extraordinary women: Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), a German naturalist and artist whose work changed everything the world knew about caterpillars in the in 15th century; Mary Anning (1799-1847), an English fossil collector who made many significant discoveries in her field and upended paleontology in her lifetime; and Maria Mitchell, an American astronomer, librarian and teacher whose achievements opened doors for women in science, at least for a little while. In a short but wonderful note at the end of the book, Atkins explains that little more than the major events of these women’s lives are known, and writing in verse gave her permission “to fill in what disappeared.” And she does so beautifully, like this line from Anning’s section:

“…certainty is like a pillow

she learned to live without.

Doubt is crucial. Discoveries are made

by those willing to say, Once we were wrong,

and ask question after question. Every one is a gift.”

This is not new territory for Atkins — along with a handful of titles that reveal the depth and breadth of her research into various women who have contributed in one significant way or another to the world — she has written three similar books, one about women in air and space, one about women explorers, and the other (her most recent, billed as a companion book to Finding Wonder) about women in math. While they have not all been written in verse, this is her second title in that format and it is one she excels at. It’s a choice that’s not only refreshing but, I think, increases the book’s accessibility — narratives about these women’s lives, and their science, that middle-grade readers can understand, connect to, and enjoy.

While I did notice a dearth of anything other than white women in both this title and Atkins’ body of work thus far (excluding Grasping Mysteries: Girls Who Loved Math), she does meet a need on the children’s market: that is, history that is not only focused on women, but women in what we now call the fields of STEM. No one else is doing what Atkins is doing and especially not in such a creative, approachable way, so for that reason alone I applaud her and this title in particular. It made me think of a line from Hope Jahren’s treatise on plant life-cum-memoir, Lab Girl, in which she writes:

“Science has taught me that everything is more complicated than we first assume, and that being able to derive happiness from discovery is a recipe for a beautiful life.”

Merian, Anning, and Mitchell were each astounding in their own right: self-educated, tenacious, and brave as hell, and their stories show very clearly discovery as a recipe for a beautiful life.

Last chance! Hit me up with your questions — really, ask me anything — because I still have two days left to fine-tune the March issue of (How) Can we read? (Simply reply to this message.)

Thanks for reading today. Have a good one 😘