(Content warning: infant loss)

In the middle of last September I sent out a regular weekly email as the unfinished draft that it was — something I’d never done before and have never even come close to doing since. I cited my reason as “heavy stuff my family was dealing with.”

The heavy stuff was a baby who passed away at the small, in-home daycare my children have attended since their own infant-hood. My daughter was at the shoulder of our daycare provider as our provider performed CPR, and she ended up being interviewed by a police officer who came by our house later that evening. She is six.

Trauma, I am learning, is rarely (ever?) a straightforward experience. My children’s grief over the past eight months has been particular — pointed and specific, and usually surprising. It often seems to come out of nowhere. I never thought that I would have to figure out how to guide them through a loss like this, and certainly not at such tender young ages. And beyond that lies my own grief: acute that afternoon I drove up the same street I drive up every day to find ambulances and a police blockade, a sight no one ever wants to connect to their loved ones, and one that has grown more muted for me since but is definitely still there. My wish for every parent, for every child’s grownup — for all of you — is never to have to approach a first responder saying, “My kids are in there.”

I wrote in April’s issue of (How) Can we read? that in our family we connect everything to literature and literature to everything. This unexpected and stunning event in our lives was no different. In fact, I’m not sure how we could have even begun to get through it without books.

It is my sincere and abiding hope that you will not have need of an issue like this, but I also recognize that, at the very least, for more than a year we have all been living in a collective grief-state that is unprecedented in our lifetimes. I also know that all of you have people you love — have maybe already lost people you love — many of you probably have pets, and there are myriad ways the human heart can attach and thus, be broken. So in some way, all of us have need of an issue like this, at one time or another.

It’s in that spirit that I offer this, as well as a list on my Bookshop.org storefront, in case you ever need to find a bunch of these books in a hurry — maybe literally overnight, like I did.

A note before we begin: before now, if my children understood death, it was mostly as an abstract concept — that afternoon last September, my 4yo especially could not and did not comprehend that her friend was never coming back. Therefore I found it most useful to read some books that explain this very directly, in an age-appropriate, concrete way (I Miss You: A First Look at Death by Pat Thomas) as well as some that are more subtle in their approach (Badger’s Parting Gift by Susan Varley). Not all loss is about death, not all grief is about loss, so some can do double and even triple duty (The Invisible String by Patrice Karst, a good book about separation of any kind).

I hope that you find something helpful here.

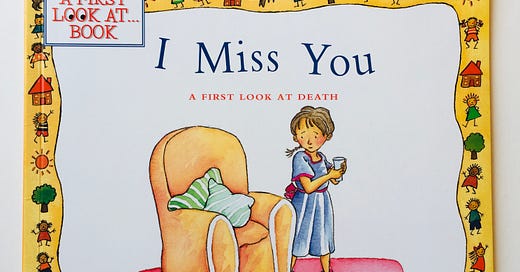

I Miss You: A First Look at Death by Pat Thomas, illustrated by Leslie Harker (2001)

In some situations, and especially with toddlers and preschoolers, you need a book that actually explains what death is, why it happens, what sometimes occurs afterwards — this is that book.

“When someone dies their body stops working — they stop breathing and their heart stops beating. They can’t think or feel anymore. They don’t eat or sleep.”

“People die for different reasons. Some people die because they are old. Some people get very sick and then they die. Some people die because something unexpected and tragic happened to them.”

“After a person dies there is usually a ceremony called a funeral. At the funeral, people who knew that person can gather together to say goodbye.”

Insofar as delivering the basic facts — including the wide range of emotions one might feel after loss of this kind, how others might respond to one’s grief — this is like no other book I’ve found. My favorite part addresses what is, of course, one of the most difficult things to explain to children, given there is no explanation: “There is a lot we don’t know about death. Every culture has different beliefs about what happens after a person dies.” This isn’t the most emotional book — it’s probably the only one I was able to get through in the immediate days after our daycare tragedy without tearing up — but it’s straightforward, thoughtfully written, and truly helpful, and I’m so grateful it exists.

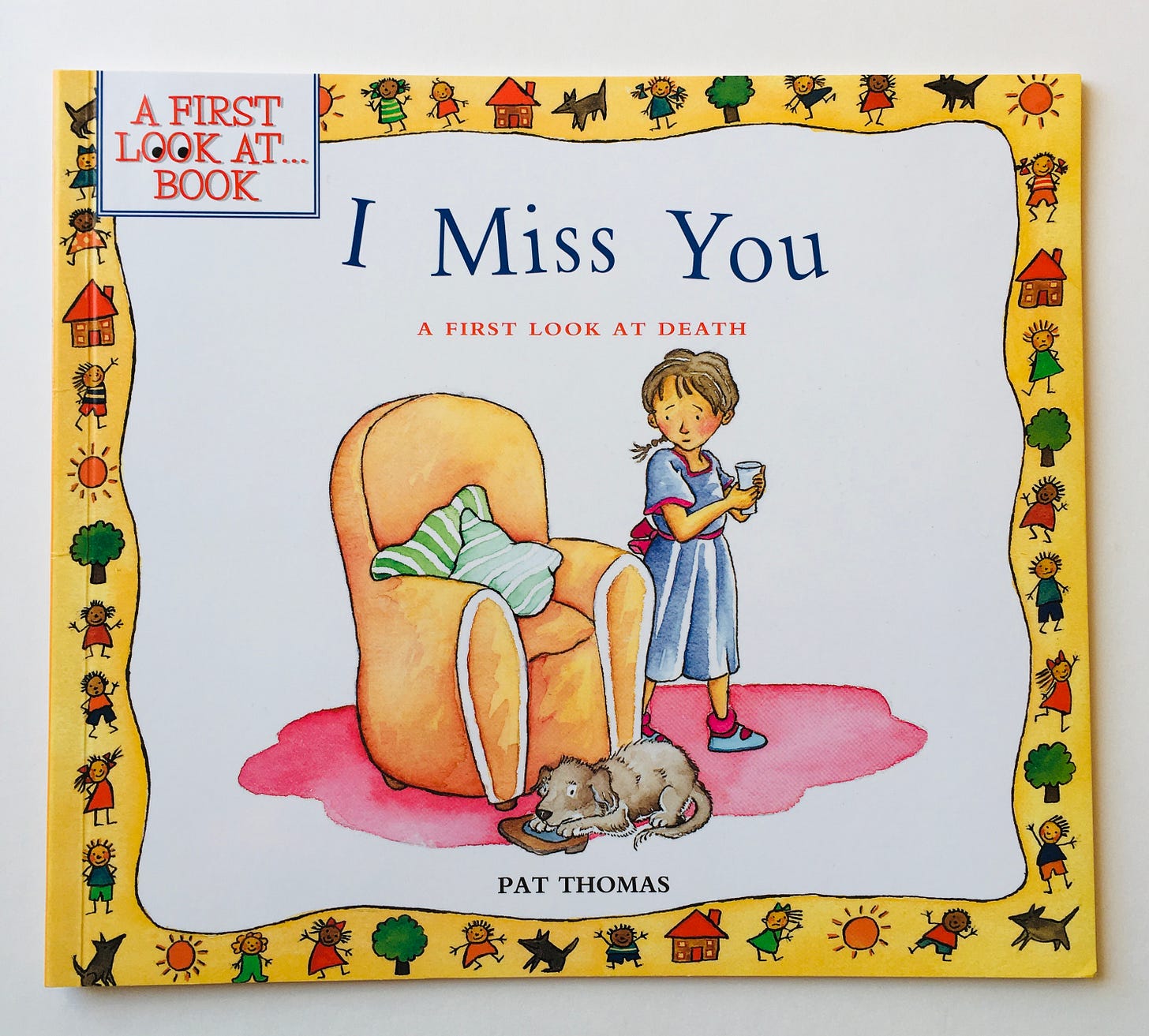

The Goodbye Book by Todd Parr (2015)

I’m a revised-opinion Todd Parr fan — when I reviewed another title of his, The Feelings Book in issue No. 3, I admitted that for a long time I didn’t understand the appeal of his work until one day I realized it is, above all, empathetic.

His books are always clear-cut, funny, and deeply understanding — addressing real topics, situations, people, and feelings in children’s lives, and The Goodbye Book is a wonderful example of that. His ability to normalize the experiences children may have is a gift, and it’s on full display here: “It’s hard to say goodbye to someone. You might not know what to feel.”

Parr’s writing is short and direct but nevertheless powerful — this is true of all his books, this one included — and always ends with a nurturing note to the reader. This is a simple book, but a wonderful one.

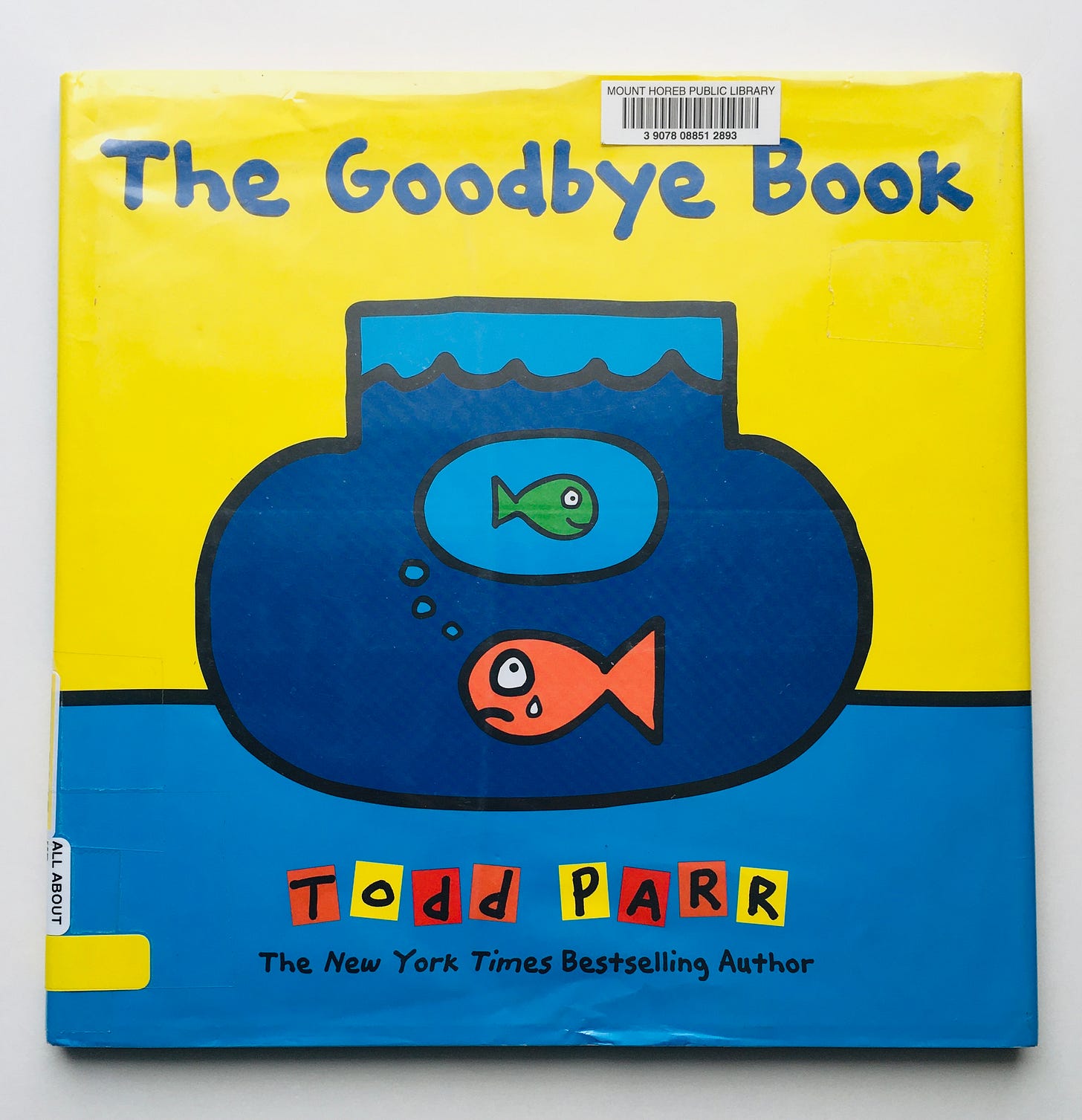

The Invisible String by Patrice Karst, illustrated by Joanne Lew-Vriethoff (originally published in 2000, reissued in 2018)

The Invisible String is somewhat of a catch-all in this category — it’s not necessarily about loss, death, and grief, but it could be.

The story begins on a stormy night when two children are awakened by thunder and run to find their mother — when the boy tells her, “We want to stay close to you,” she replies, “You know we’re always together, no matter what,” and explains that even when they are apart from one another, they are connected by “the invisible string,” “a very special String made of love… you can feel it in your heart and know that you are always connected to everyone you love.”

The rest of the book offers scenarios that test the string: can one feel its tug? Who does it connect? How far can it reach? On one page, one of the children asks it if can reach their uncle in heaven (the answer is yes — something to be aware of if heaven is not part of your belief system), and this is the only instance where death is addressed, but the topic is folded so naturally into the narrative, it’s hardly the focal point of the story. The emphasis here is on the invisible strings that connect us all, and as such, the soothing idea that no one is ever alone.

I have used this title for years with my own children as we’ve gone through various ages, stages, and random struggles with separations due to daycare, school, travel for work — so while this definitely fits into the category of this particular special edition, it’s also just a good one to have on your bookshelf for those times when hearts need an extra dose of comfort and reassurance.

Originally published in 2001 (illustrated by Geoff Stevenson), the edition featured here is a reissue that came out in 2018 (illustrated by Joanne Lew-Vriethoff). I vastly prefer the reissue — Karst’s prose is the same but Lew-Vriethoff’s digital illustrations are far superior to Stevenson’s pen-and-ink line drawings, which in my opinion look too comical for the gravity of the topic (why shouldn’t separation anxiety be treated with the seriousness with which it’s felt?). There is also a 2020 follow-up title by Karst, The Invisible Web, that takes this concept a step further and goes beyond the experience of two children connected to their loved ones via invisible strings to people connected by invisible strings all over the world — certainly an intriguing notion during a pandemic, if nothing else.

Nana Upstairs & Nana Downstairs by Tomie dePaola (1973)

I have never once been able to read this book without crying, so I stopped trying and just let it flow.

This deeply touching story is true — it’s dePaola’s recounting of his special relationship with his grandmother, Nana Downstairs (because she is always in the kitchen, standing by the stove), and great-grandmother, Nana Upstairs (because she is always in her bed), both of whom he loves very much. He visits them every Sunday afternoon, relishing the time spent together doing specific things. Nana Upstairs is so old (94yo) that Nana Downstairs has to tie her in her chair to keep her from falling out — Tomie (4yo) thinks this is so fantastic, he asks to be tied to his chair, too.

The relationship little Tomie has with both women is so full of love it practically spills off the page, so when one day his mother tells him that Nana Upstairs passed away last night, he is devastated. The images of his grief are real and wrenching — when he looks out his bedroom window and sees a shooting star, his mother says, “Perhaps that was a kiss from Nana Upstairs.” Years later when Tomie’s Nana Downstairs (who by now he just calls Nana) dies, he sees another shooting star and thinks, “Now you are both Nana Upstairs.”

Like I said, I never make it through this — it has so much heart, and so much heartbreak, it’s extremely difficult and comforting all at once. Which, if you think about it, is a pretty good definition of grief.

Blackberry Stew by Isabell O’Connor, illustrated by Janice Lee Porter (1999)

Blackberry Stew is the lovely story of a little girl named Hope who is afraid to go to her grandfather’s funeral, for fear that once she says goodbye, she’ll never see him again. Her aunt questions Hope’s concerns (in the way of a loving witness, rather than a critic), saying, “Never see him again? You really think so?”

When Aunt Poogee closes her eyes she sees her brother in her mind, and shares this remembering with Hope, who then begins to “see” Grandpa Jack too. She relives a day last summer when she and her grandfather went blackberry picking in order to make an old family recipe — Blackberry Stew — and something unexpected happens.

Lee Porter’s oil paintings are vivid and expressive, an excellent complement to Monk’s prose in telling the story of that day — there is a warmth here, not only between the family (their love and enjoyment of each other’s company is evident) but in tone and feeling, helping the reader to understand that for Hope, this one particular day with her grandfather is a microcosmic way of explaining the larger macrocosm of his love. It’s after reliving this memory — and understanding that the people we lose live on in our memory — that Hope is finally ready to go to the funeral.

This is a rich, gentle tale — direct in its subject matter to be sure, but shared in a way that seems to indirectly attend to the heart. I can’t think of a better way approach.

The Star People: A Lakota Story by S.D. Nelson (2003)

Of all the books on loss, death, and grief I have read for our own purposes and this issue, this is my favorite: it’s the most spiritually beautiful, the most hopeful, and offers the most soothing suggestion of what might happen after we die. (I for one struggle mightily with answers to questions about the afterlife so anything that helps me put images and words to the mystery is welcome.)

Here a sister and a brother, Sister Girl and Young Wolf, wander far across the prairie one day, watching the clouds drift overhead and discussing what they see. Just as they spot their grandmother’s face in a cloud (she had died that spring and they missed her deeply), the two children are caught in a sudden prairie fire and become lost. When they are safe, they try to stay calm and gather themselves, and realize that “the stars are dancing.” Above them in the sky, the Star People encircle them — Sister Girl recognizes them as “the spirits of the Old Ones who once walked on this earth” — including their grandmother, who soothes them, and the next morning leads them home.

Her reassurance of her grandchildren that “I will always be with you. The Star People are always with you. Look up, and you will see me among the stars” is the crux of the message here: that our loved ones live on in the stars above us, that we haven’t lost them entirely because they are always there if only we remember to lift our eyes.

Nelson, a Lakota author and artist, member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, has written a handful of outstanding books for children, and this one rises to the top for me. A gorgeous story accompanied by even-more gorgeous illustrations (done with acrylic paint on watercolor paper, in a style that is a contemporary interpretation of traditional Lakota ledger book art, as Nelson explains in a lengthy author’s note at the end), there is magic here — the kind of heart magic that makes absolute sense.

The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota's Garden by Heather Smith, illustrated by Rachel Wada (2019)

When I first heard about the real-life location this book is based upon — a “wind phone” located in a telephone booth in Ōtsuchi, Japan, the express purpose of which is to allow callers to hold one-way conversations with deceased loved ones, created by an artist after the loss of a family member in 2010 and then opened to the public following the devastation of the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami (15,000 people were killed) in 2011 — I couldn’t get it out of my head. The idea is so beautiful and so heartbreaking all at once. So when I came across The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden, I wanted to read it immediately, and I was not disappointed.

Here, fiction sticks closely to fact: Makio is a young boy who loses his father to a tsunami, which he just happens to witness with his neighbor, Mr. Hirota. Afterwards, Mr. Hirota builds a phone booth in his garden, inside which Mr. Hirota and other villagers make calls — though they can see and fully understand that the old-fashioned phone has no plugs or wires, is “connected to nowhere.” Eventually, Makio makes his own call to his dad, in what is the most difficult part to read aloud.

It’s hard to fully communicate how moving this story is — it is full of raw sorrow and even anger, but there are also threads of resilience, community, and the myriad unexpected, even creative ways people can heal. Early in the book, Smith recognizes that while this story is specific to one boy, it’s also applicable to many, writing, “Everyone lost someone the day the big wave came.” The message here is subtle: yes, this is a particular wave on a particular day, but death itself is a wave that can come from nowhere and sweep us up at any time, and for those of us who have lost someone, can’t we relate to that?

Smith’s execution is masterful — every word matters, every word carries weight — and I’d say her writing is the best part of this book if Wada’s watercolors, black ink and pencils (inspired by traditional Japanese techniques) weren’t so incredibly well-done, dark and emotional and perfect. This is a brilliant read and perhaps an even more brilliant idea — convincing enough that I have been keeping an eye out for an old phone, thinking that maybe, in our house, we might like talking to the wind.

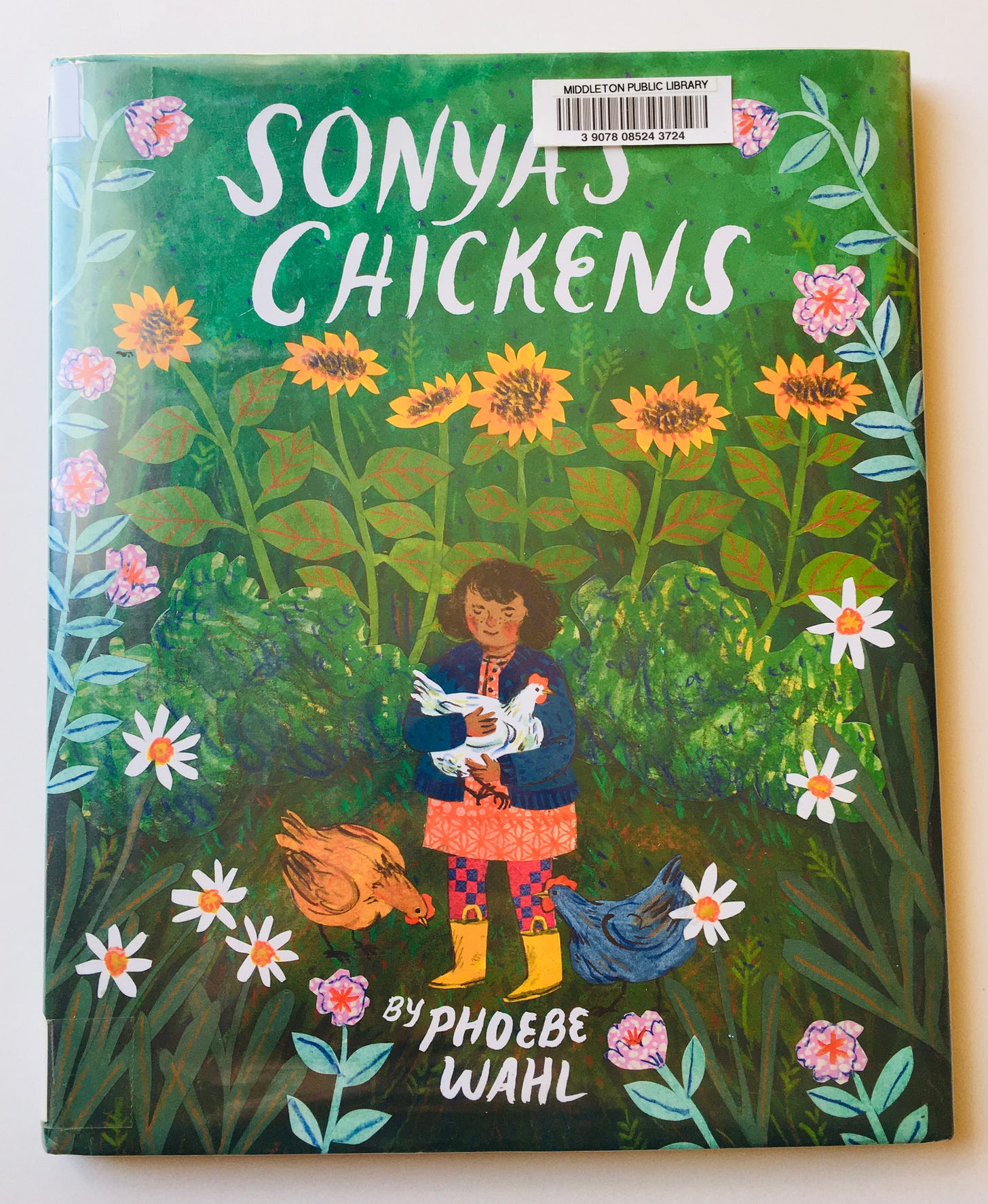

Sonya’s Chickens by Phoebe Wahl (2015)

The day her Papa comes home with three fluffy chicks, Sonya immediately takes to the idea of being their mother — she cares for them first in a cardboard box in the house, tucking them in her sweater for warmth, and then in their coop in the yard, tending them with enough care and consistency that they grow to become hens and lay eggs of their own.

One evening, despite Sonya’s diligence in seeing them safely into their coop every night, she wakes “to a ruckus of squawking and shuffle-y bump noises from outside” — anyone who has ever owned chickens is probably familiar with this sound, and Sonya, of course, finds to her great heartbreak that one of her beloved chickens did not survive a sneak predator attack. Her father tries to console her by telling her a possible story of the chicken’s demise from the fox’s point of view — the fox has babies of his own to take care of and must work hard every day to keep them alive; he took Sonya’s chicken not out of malice but because it was a chance to feed his family.

This logic (a stroke of parenting genius, I think) makes enough sense to Sonya that she is able to accept her loss. The family has a small funeral for the lost chicken. They repair the damage to the coop that the fox wrought. And then one day, an egg hatches, and Sonya has another little chick to take care of.

I am a big fan of Wahl’s — her books are tender (frequently dealing with heavy stuff*), often rooted in nature, and kind of inexplicably magical. She’s a talented artist and her watercolor, collage, and colored pencil illustrations are vivid and full of emotion. All of this combines to create a read that’s equal parts empathetic, understanding, and kind — my favorite title for the loss of an animal, but also a pretty good reminder for loss of any kind that sometimes things happen that are out of our control, and it’s okay to grieve that.

*see The Blue House for another title with themes of loss, this one about a house and a forced move

Also highly recommended

Goodbye Mousie by Robie H. Harris (loss of pet)

Life is Like the Wind by Shona Innes

The Boy and the Gorilla by Jackie Azúa Kramer (loss of mother)

The Rough Patch by Brian Lies

Lifetimes: The Beautiful Way to Explain Death to Children by Bryan Mellonie and Robert Ingpen (this is poetic and lovely but might be a little too subtle for younger children)

Rain Before Rainbows by Smriti Prasadam-Halls (not specific to loss or grief, this is a heartening, hopeful title for any kind of difficult time)

Life by Cynthia Rylant (also not specific to loss or grief, but a soothing and beautiful read)

Badger’s Parting Gift by Susan Varley

Saturdays Are for Stella by by Candy Wellins (loss of grandparent)

Death of a loved one

Boats for Papa by Jessixa Bagley (father)

Grandma’s Gloves by Cecil Castellucci (grandparent)

Grandpa’s Stories: A Book of Remembering by Joseph Coelho (grandparent)

Grandad’s Island by Benji Davies (grandparent)

A Stopwatch from Grampa by Loretta Garbutt (grandparent)

Ghost Wings by Barbara Joosse (grandparent)

Northern Lights: The Soccer Trails by Michael Arvaarluk Kusugak (mother)

Liplap’s Wish by Jonathan London (grandparent)

Stones for Grandpa by Renee Londner (grandparent; Jewish tradition)

Where Are You? A Child's Book About Loss by Laura Olivieri (unspecified parent)

The Forever Sky by Thomas Peacock (grandmother)

Holes in the Sky by Patricia Polacco (grandmother)

The Forever Garden by Laurel Synder (friend)

One Wave at a Time: A Story About Grief and Healing by Holly Thompson (father; I especially like how this explains different aspects of grief and that the feelings come in waves)

Dear Moon by Stephen Wunderli (friend, a child who has a terminal illness)

Death of a pet

A Stone for Sascha by Aaron Becker (wordless)

Remembering Barkley by Erin Frankel

Daniel Tiger: Remembering Blue Fish adapted by Becky Friedman

When a Pet Dies by Fred Rogers (I love the entire First Experiences series by Rogers, even if the photos are dated)

Goodbye Vivi by Antoinette Schneider

The Tenth Good Thing About Barney by Judith Viorst

I'll Always Love You by Hans Wilhelm

Unspecified or general loss

Sarah’s Willow by Friedrich Recknagel

Tear Soup: A Recipe for Healing After Loss by Pat Schwiebert and Chuck DeKlyen (not just for children; this one also includes pages of resources in the back)

Everything else

Goodbye, Friend! Hello, Friend! by Cori Doerrfeld (friend; child moves away)

The Rabbit Listened by Cori Doerrfeld (not specific to loss or grief, this is the best book about allowing feelings and empathy I’ve ever come across — I reviewed it in issue No. 13)

A Separate Peace by John Knowles

Ida, Always by Caron Levis

Evelyn Del Rey is Moving Away by Meg Medina

Chester Raccoon and the Acorn Full of Memories by Audrey Penn

Wherever You Are: My Love Will Find You by Nancy Tillman (not necessarily about loss, could be a separation of any kind, but a reassuring read nonetheless)

Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

Where Only the Elders Go: Moon Lake Loon Lake by Jan Bourdeau Waboose

The Dead Bird by Margaret Wise Brown

If you ever are in need of this issue and cannot, for whatever reason, see clearly enough through the feelings to pull it up from the recesses of your email archive or the internet, just send me an email — I will immediately resend this your way.

And: please feel free to forward this issue if there is someone in your life who needs it.

Peace to you,

Sarah

I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you make a purchase through my storefront.

I am so grateful for this list. Your email today, June 18, came into my mailbox about the same time I was saying to my husband, "I'm just full of so much grief." I have family issues concurrently with a grand baby, with a child, and with my parents at the moment and I'm living in a deli sandwich of grief. Reading through this full story gave me the cry I needed. You are a blessing. Thank you for blessing me.

What a great list - I always appreciate your recommendations. I stumbled upon Duck, Death and the Tulip by Wolfgang Erlbruch some time ago in Germany and was blown away by its completely unsentimental representation of death. See more here: https://www.themarginalian.org/2016/05/04/duck-death-and-the-tulip-wolf-erlbruch/