For two weeks, we’ve been taking a deep dive into fairy tales. Last week I explained the why behind reading fairy tales to kiddos (even the scary ones) in Part 1 and started off with some recommended titles in Part 2. Earlier this week I shared an example from my own life as to how these stories apply and made more suggestions in Part 3. That’s what I’m doing again today, because you can never have too many options — at least when it comes to books 😊

Next week we’ll return to our regularly scheduled programming.

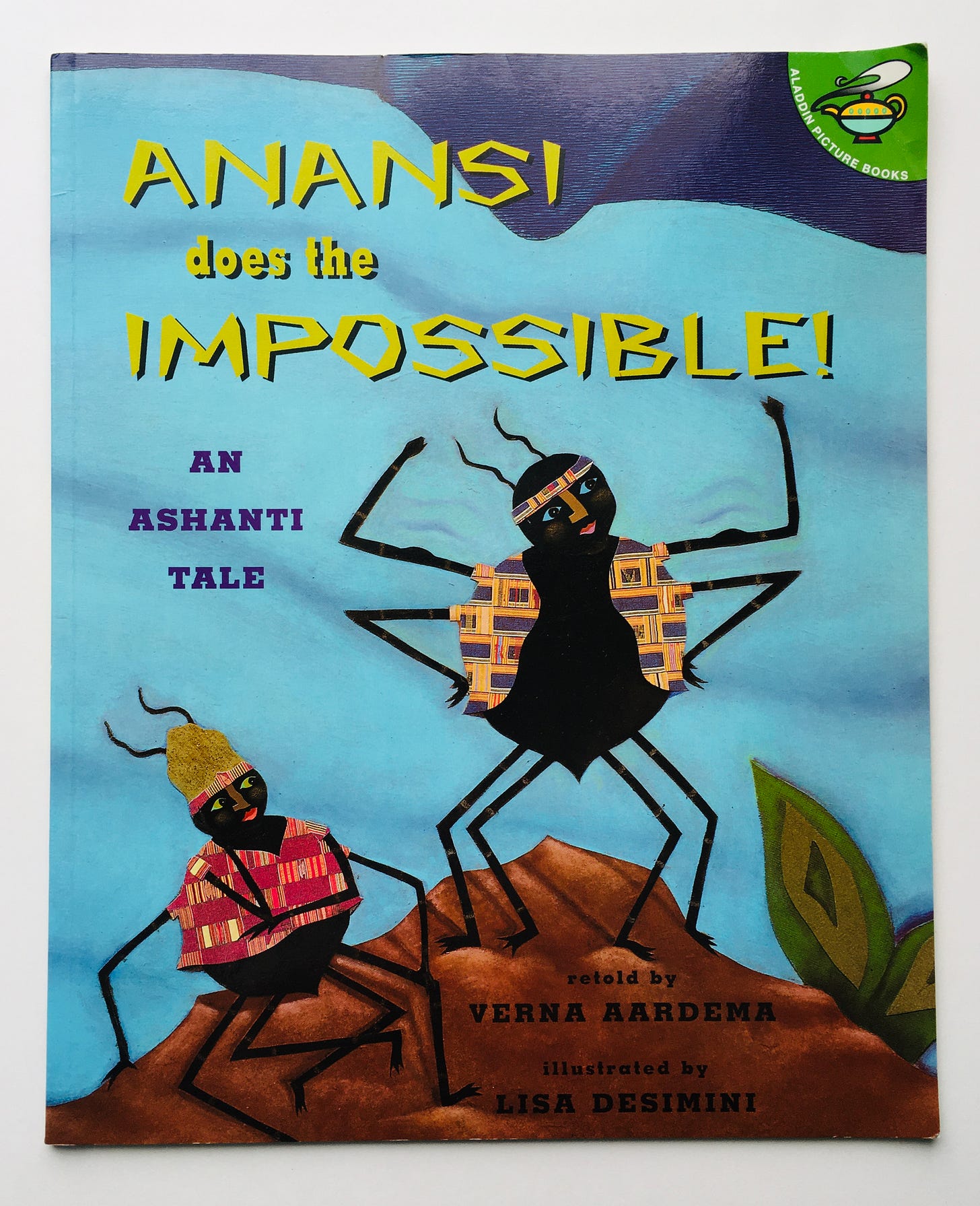

Anansi Does the Impossible: An Ashanti Tale retold by Verna Aardema, illustrated by Lisa Desimini (1997)

There are a handful of titles out there about Anansi — a trickster spider, sometimes depicted as a god, who is the hero in many tales told by the various peoples that live around the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa, who has also migrated on occasion to both Caribbean and African American folklore. But I especially love this one from Verna Aardema, in whose capable hands the figure of Anansi comes alive as only he can.

Here, Anansi is tired of the fact that “all folktales were owned by the Sky God,” and heads up a mountain to buy them back. The Sky God refuses, but sets as his price three impossible tasks — if Anansi can bring the Sky God “a live python, a real fairy, and forty-seven stinging hornets.” Sure, okay. Anansi heads home to confer with his wife, Aso, who is cautious and wise. Together they hatch three clever plans to complete the tasks, and three times they succeed — the small once again triumphing over the big.

Anansi is always portrayed as some combination of rogue and wise, but what sets this particular title apart is Aso’s role — she is the one who comes up with the solution to the problem of solving each task, and without her Anansi, who performs the physical feats of daring, would never pull off any of it. Aso is intelligent — the real brain against the Sky God’s brawn — and not merely a shrewd advisor: she is an equal partner to Anansi, and as such, they truly share their success.

Desimini’s oil paint and cut-paper illustrations add visual interest with their bright, even unusual images (how one can capture a spider’s facial expression with bits of paper is beyond me, but she has done it to great effect). Matched with Aardema’s prose, this team fully communicates Anansi’s trickster nature along with something else rather more important: Anansi is beloved by children for being a mischief maker, and, I think, for being a rare character to whom they can easily, immediately relate: when you’re small you don’t often get the chance to best the bigger folks, and Anansi does it every time. That’s hopeful, and often funny, and always satisfying.

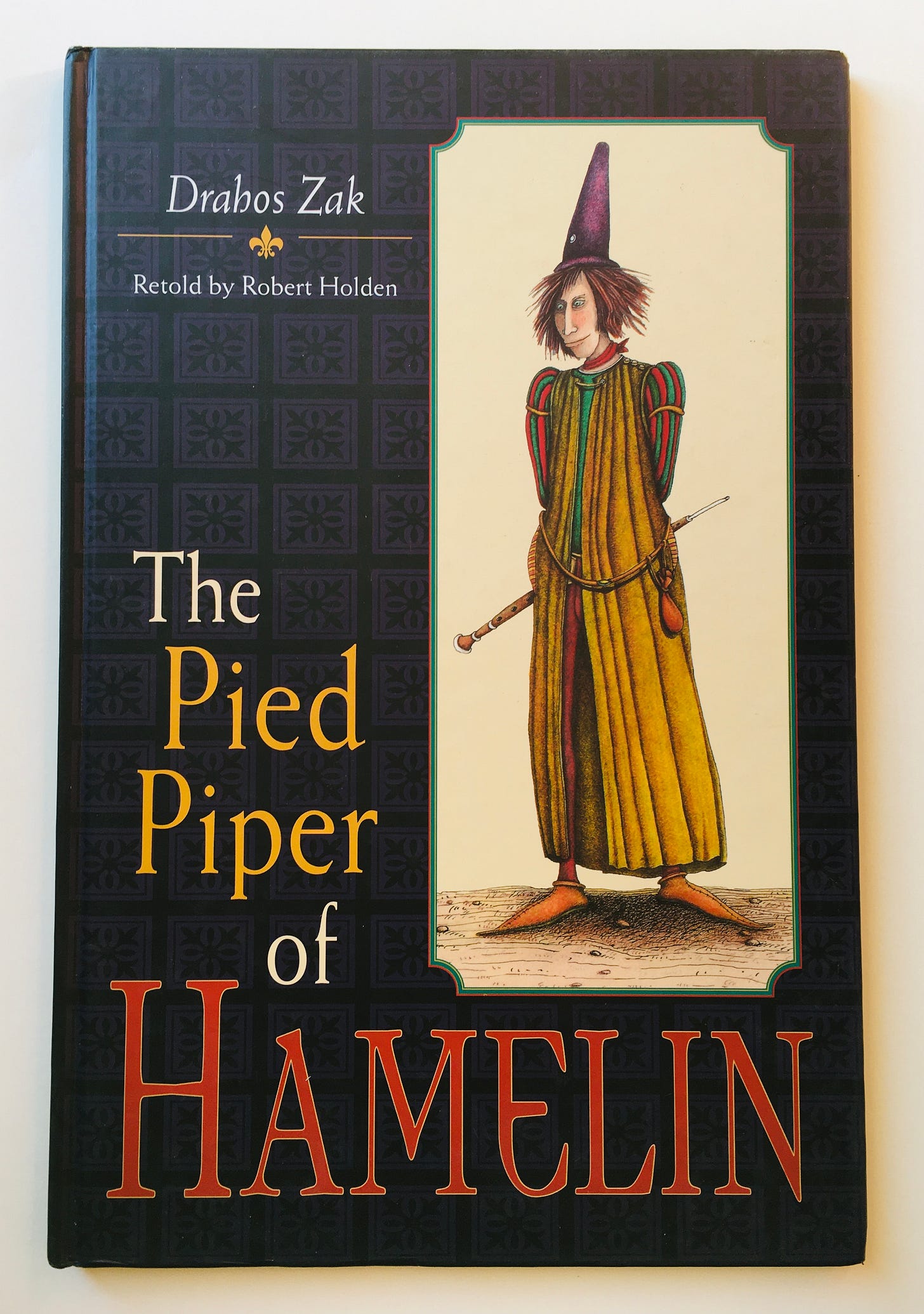

The Pied Piper of Hamelin retold by Robert Holden, illustrated by Drahos Zak (1997)

Told in short rhyming verse, this story of a 13th-century town that called in a rat-catcher to help them with an infestation problem, refused to pay him, and lost all their children when he hypnotized and stole them away has scared me since the moment I watched it as an episode of Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre as a young child in the 80s.

Imagine my horror when, upon reading this (again and again and again) with my then-4yo who loves to scare herself — which Zak plays into with his creepy and grotesque illustrations to perfect effect — I looked into it further and discovered that it’s possibly a true story. WHAAAAT! 🤯

There are other good renditions of this tale out there, but there is something extremely satisfying about this one. Since it is told in verse, what is actually happening in the story is somewhat subtle — it took many questions and much conversation before said 4yo really understood that the Piper took the children — which means that it rewards repeated reading (win!) It’s not always easy to pull off an entertaining telling of a less popular tale — Holden’s condensed prose combined with Zak’s formidable talent just really works.

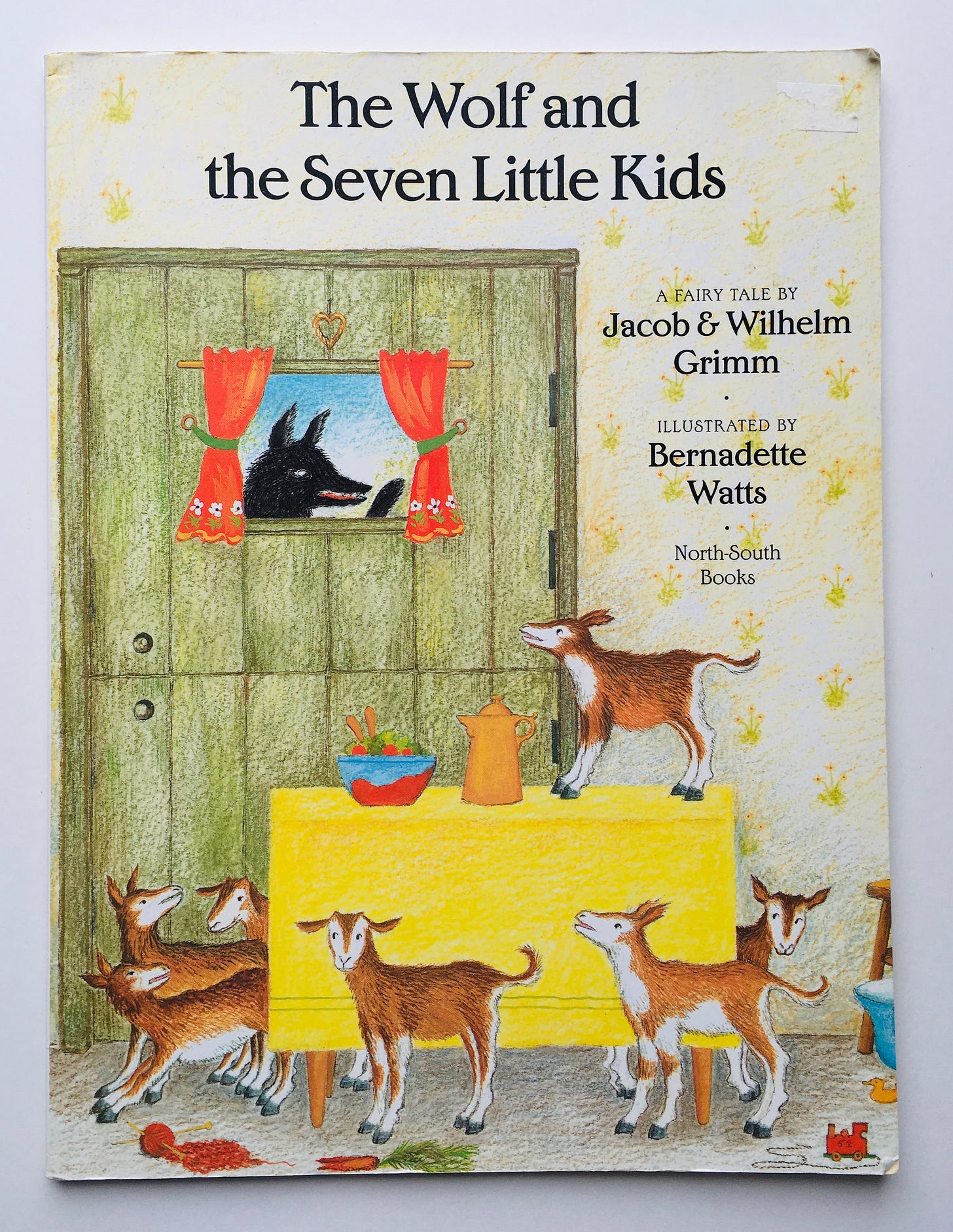

The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, illustrated by Bernadette Watts (1995)

When I first encountered this title several years ago, I was unfamiliar with the Grimm’s story, “The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids,” especially how it differs from “Little Red Riding Hood” (purported to be written by Charles Perrault for the court of King Louis XIV, who directly explained that the moral of his story was intended to warn young women of the dangers of strange men) or “Little Red Cap” (collected by the Brothers Grimm, but also sometimes mixed up along the way with “Little Red Riding Hood”). But, though it’s similar in one major respect — there is wolf who intends to feast upon relatively defenseless creatures using trickery and disguise — it is, really, an entirely different story.

In it, an Old Mother Goat warns her children of the dangerous wolf who will want to come inside and eat them up while she is away in the woods — and, predictable old fellow that he is, the wolf appears and attempts to do just that. Eventually he succeeds, eating up all the kids but one, who is discovered inside a grandfather clock by his mother upon her return, and together they go out to rescue the others — by cutting open the wolf’s belly while he sleeps to release the kids, filling him up with rocks, and sewing him back up again — while the wolf, upon waking, falls down a well and dies.

(Honestly, even as an adult, I often feel satiated by the justice of fairy tales. And — Perrault’s motivations aside — sometimes I think of a Germanic mother once upon some centuries ago, coming up with a frightening tale about a wolf who will eat little children if they don’t listen, and I chuckle.)

Watts’ work is highly accessible, both in terms of her choice of tales and her style, to the youngest crowd. This is a simple story simply told, but done oh-so-well.

The Talking Eggs by Robert D. San Souci, illustrated by Jerry Pinkney (1989)

The Talking Eggs, San Souci’s Creole-adapted folktale, begins much like some other familiar ones in the genre — Rose, the older sister, is “cross and mean” and not very smart, while Blanche, the younger sister, is “sweet and kind and sharp as forty crickets.” Their mother likes Rose best and makes Blanche do all the work of the house, because that is the way things go in these stories.

One hot day the mother sends Blanche to the well for water, where she finds an old woman “fainting with the heat.” She helps the woman gladly and generously — because this is also the way things go in these stories — and as such, the old woman tells her, “You got a spirit of do-right in your soul.” When Blanche returns home, her mother and sister cast her out, so she returns to the woods and, as it happens, to the old woman, who offers Blanche a warm, safe place to stay so long as she promises not to laugh at anything she sees.

Blanche promises.

When they arrive at the old woman’s “tumbledown shack,” there are all sorts of wild things to be found: a cow with two heads, rainbow-colored chickens, and the inside isn’t much better: while Blance is lighting the fire, the old woman removes her head.

Mysteries abound, more bizarre (magical?) things occur, and like all good folk and fairy tales, Rose receives her due — it’s one of the creepiest scenes I’ve read in a picture book, which Pinkney’s dense, evocative watercolor illustrations make all the more satisfying — and she, along with her mother, disappear forever.

Do traditional tales of good and evil ever get old? You tell me. We love this one for its lush beauty and its simple reassurance that there is order in the universe: that bad people come to a bad end, and good ones are rewarded. (So be sure to choose the plain eggs.)

Fairy Tales and Fables by Gyo Fujikawa (1970)

Gyo Fujikawa changed the world of children’s literature almost overnight when, in 1963, she depicted an Asian child in her first title, Babies — the first non-white child ever to be depicted in a children’s book. She went on to include children of many races in her work thereafter, during a time when doing so was absolutely groundbreaking. (If you’re interested in Gyo Fujikawa’s story, I recommend this 2019 article from The New Yorker, and a really well-done 2019 children’s book about her life, It Began With A Page: How Gyo Fujikawa Drew the Way by Kyo Maclear.)

All of her titles are good, some excellent, and though this one is not an original written work — it’s a compendium of fairy tales and folktales, which arguably belong to everyone and no one — it’s a gem, and maybe more importantly, an easy, evocative and inexpensive way to start the process of sharing folk and fairy tales with children, if you haven’t already. (Plus, I think Fujikawa’s illustrations are just about the cutest I’ve ever seen.) This is one to purchase and enjoy.

Of special note: audio

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the exceedingly excellent podcast, Family Folktales from the Nashville Public Library.

The narrator of each episode, Susan Poulter, is a librarian who reads almost (but not entirely) exclusively from Andrew Lang’s fairy books.

If the stories seem old-fashioned, or perhaps too advanced for young children, remember that “reading up” — the idea that kids can listen to books and stories far above their reading level and should regularly be exposed to this, as it builds vocabulary, increases comprehension, and improves listening skills — works.

Want even more where this came from?

I have a booklist on Bookshop.org of my recommended folk and fairy tales — many more titles than I’ve reviewed here. As always, if you make a purchase using this link, I get a small commission, which is a way to support this newsletter without an additional cost to you, and you get books! What’s not to love?

Thanks for joining me on this journey through folk and fairy tales. I hope you’ve enjoyed it and, far more importantly, found some new-to-you titles to read and share.

Sarah

I am a sucker for all things Anansi so I will definitely be looking for the one you’ve recommended here. Thank you for such a thoughtful list!

The Talking Eggs was one of my absolute favorites when I was in school! I need to share it with my daughter.