For two weeks, we’re taking a deep dive into folk and fairy tales, over four posts. Last week I explained the why behind reading fairy tales to kiddos (even the scary ones) in Part 1 and started off with some recommended titles in Part 2. Today and Thursday I’ll make more suggestions to help you find some additional options that will delight and resonate with you and your readers.

And, here’s a real-life example of why: last Wednesday, there was an active shooter at my children’s school district. This sounds like, oh, it happened across town, but in my small village of 8,000 people, no — grades 3-12 are spread among three buildings on a combined campus, and grades K-2 are in two buildings next to each other a few blocks away. The assailant — a 14yo male in 8th grade — brought a gun to the middle school, tried to gain entry in all the horrific ways you can imagine, did not succeed, and was shot and killed by police in the process.

As one of my best friends, writer, editor, and author Maggie Ginsberg wrote on Instagram: “All of my people are safe and no one is okay.” It’s the single best explanation, when I have no explanation whatsoever, when I am, for one of the only times in my life, absolutely without words: All of my people are safe and no one is okay.

There are so many details and layers and almost nothing we know for sure — still — and every last bit of it is heartbreaking. My husband and I waited for more than six hours without real information until we were finally able to put our hands on our children, their cheeks in our palms, their sobbing selves against ours, and others waited seven, eight, nine — at the library, at the church, at the bus garage. More than once, I simply left my body.

(To my librarians who are reading this — you have been “my librarians” for the past 15 years but now you will be my librarians forever, wherever I live, wherever I go — thank you for sheltering 500 children of Mt. Horeb. For opening your doors and receiving them all, running, when you didn’t know they were coming. For caring for them, like you always care for them. For proving a thousand times over that libraries are shelters from the storm, sometimes literally. Again: no words.)

When I put my children to bed that night — or, more accurately, when they snuggled down in my bed, where they asked to sleep, one on each side of me — I had no idea what to read. How could anyone read right now? How could anyone want to?

You think fairy tales aren’t relevant, with all their inscrutable cruelty and violence, abrupt endings, darkness the likes of which monsters are born or made: try tucking your 9 and 7yo under your arms the day they survived a school shooting, with all that trauma and whatever’s still to come, and your favorite version of Grimm’s.

You’ll understand.

(And I hope you never, ever understand.)

The Little Mermaid by Jerry Pinkney (2020)

Honestly, if you see a book by Jerry Pinkney, just buy it — you can never go wrong with one of his titles, and his reimagining of this Hans Christian Anderson story is no different.

Here the reader meets Melody, the youngest mermaid in her family, a mer-girl full of curiosity and creativity, not content to merely sing in the choir with her sisters. Though she is aware of the dangers of the Sea Witch, one day she follows her guardian sea turtle to the surface, where she spots a friend, a figure with “two sticklike legs” — a human!

This is where Pinkney’s decision to change both the original and the Disney versions of the story (one where the mermaid ends up dying, the other where she ends up married to someone who never struck me as even remotely interesting or worthy — GET A PERSONALITY, ERIC) is most refreshing and appreciated: Melody strikes a devil’s bargain with the Sea Witch in order to make it up to land, and though there are great challenges to overcome and a heartbreaking decision to make before the end (which may be happy or sad, depending on your interpretation), all this is done for a friend, not a man.

Add to this Pinkney’s truly immense talent as an illustrator — he outdid himself in this title with pencil and watercolor images that are absolutely stunning — and you have the best new fairy tale to be found.

Tatterhood and Other Tales by Ethel Johnston Phelps (1978)

There are so many things to love about this collection I don’t know where to begin.

The tales in Tatterhood are not traditional stories rewritten or modernized by Johnston Phelps to make the women, you know, human beings instead of prizes some prince or warrior or dumb idiot wins for accomplishing an impossible task or saving a kingdom or what have you — rather, they are fairy tales long in existence but buried beneath all the male-dominated ones in various cross-cultural collections.

I love them for this reason alone, but no stories win my whole praise if they don’t delight my children, and that’s the thing with Tatterhood — when I read this to my kids at bedtime, ostensibly in an effort to calm and soothe them, their eyes get wide and they often cannot remain lying down, so eager are they to hear what’s about to happen. These tales turn every traditional frailty, thy name is woman, damsel-in-distress narrative on its head and they are compelling as all get out.

Johnston Phelps’ work — the companion to this title is another excellent collection called The Maid of the North: Feminist Folk Tales from Around the World — is both antidote and balm to the history of folk literature as most of us know it, and I strongly encourage applying it.

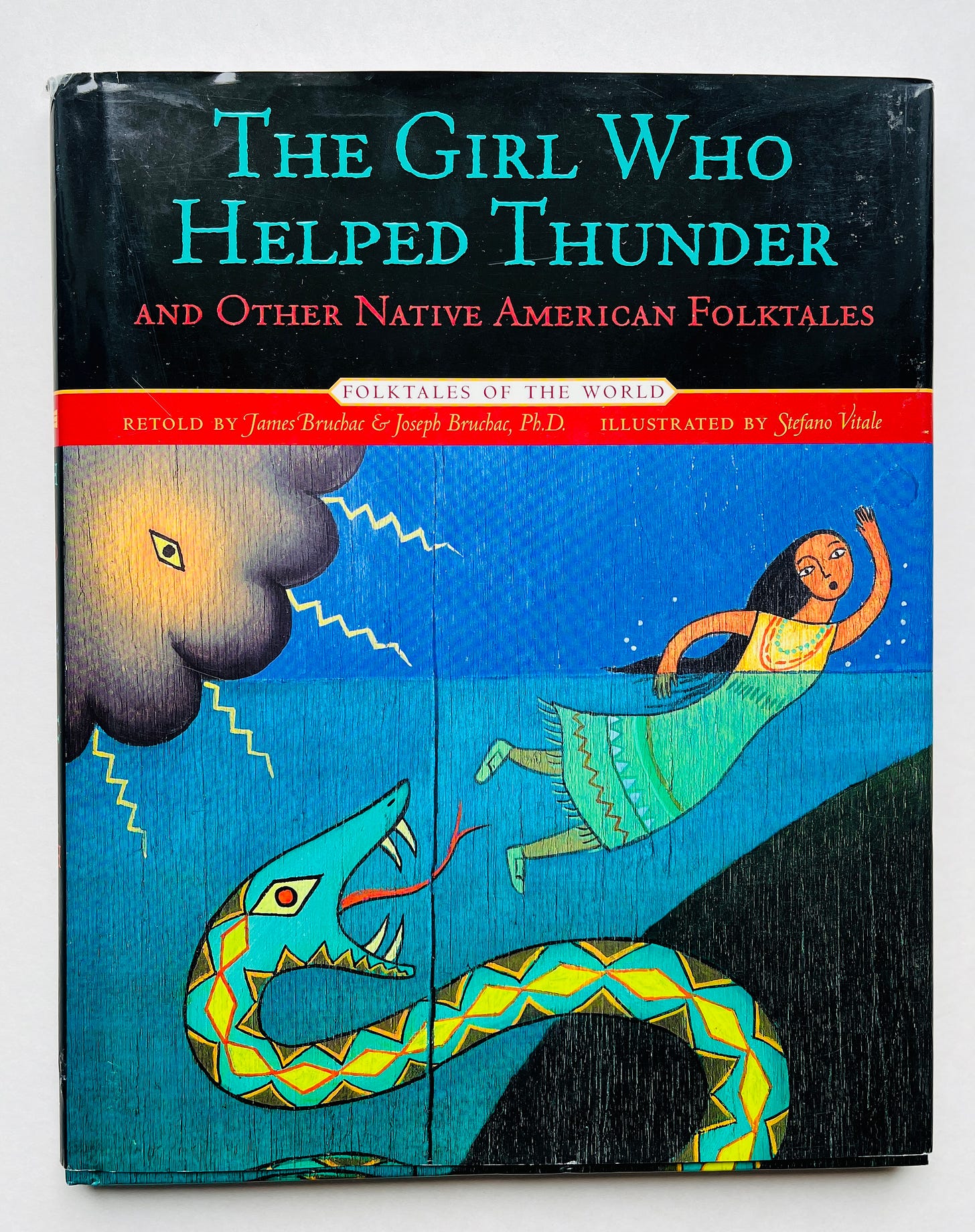

The Girl Who Helped Thunder and Other Native American Folktales retold by James Bruchac and Joseph Bruchac, illustrated by Stefano Vitale (2008)

It’s rare to come across a collection of Native folktales as culturally and geographically diverse as this one — as I write these words and try to think of another one, I can’t come up with anything — so I especially appreciate this collection from father/son team, James Bruchac and Joseph Bruchac, both experienced storytellers and increasingly prolific authors of Abenaki descent (though I recognize that is currently up for debate).

Vitale’s acrylic-on-wood illustrations, reminiscent of folk art, accompany a broad and deep span of stories that range in topic from “How the Rabbit Got Wisdom” (Creek) to “Why Owl Lives Away From People” (Wiyot) to “Why Moon Has One Eye” (Isleta Pueblo), from Native nations in the Northeast, Southeast, Great Plains, Southwest, California, Northwest, and the Far North. Sections are divided geographically, with a short introductory page before each one that catalogs, in an entirely accessible way, the major cultural groups and nations within.

This would make an outstanding addition to any home or classroom library where kiddos are either good listeners, good readers, or both — this is, essentially, for everyone. Some stories might please children as young as preschool; many more will appeal to children up through middle school. Regardless of age, these folktales appeal to anyone interested in the topics that possess us all: life, death, love, power, heroism, intelligence, generosity, jealousy, kindness, community. These are stories for the world, about the world.

Toads and Diamonds by Charlotte Huck, illustrated by Anita Lobel (1996)

Originally written by Charles Perrault, this story of a good-hearted stepdaughter who is treated like a servant has some similarities to Cinderella, but there is enough difference here to make it a fresh tale.

When Renée is one day sent to a well, she runs into an old woman and gives her water. For her kindness, the old woman blesses her with the gift of a jewel or a flower coming out of her mouth whenever she speaks. When Renée’s stepmother sees this, she sends her own daughter to the well — of course, this daughter is unkind to the old woman (who by now has taken other guises, as she’s a magical being), and her punishment is for a toad or snake to fall from her mouth whenever she speaks.

The dichotomy between good and bad is extremely cut-and-dried here — Renée’s compassion and selflessness is rewarded, her step-sister’s nasty and uncharitable heart is punished — there is no nuance whatsoever, though Huck’s retelling is well-written and Lobel’s illustrations are as masterful as ever.

It’s an example of what Bruno Bettleheim explained as “symbols of psychological happenings or problems” rather than reality, and that’s okay — the justice, along with the whole story, is gratifying.

Revolting Rhymes by Roald Dahl, illustrated by Quentin Blake (1982)

Leave it to wicked, hilarious Roald Dahl to take a handful of classic fairy tales — Cinderella, Jack and the Beanstalk, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf, and The Three Little Pigs — and turn them into wicked, hilarious poems.

If your children are familiar with the original stories — and ready for narrative revisions and some language that’s a bit more vulgar than what you’d find in tamer retellings — then this is the book for you.

Take this bit from “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” after the bears have headed out for a walk because their breakfast is too hot:

No sooner are you down the road

Than Goldilocks, that little toad

That nosey, theiving little louse,

Comes sneaking in your empty house.

She looks around. She quickly notes

Three bowls brimful of porridge oats.

And while standing on her feet,

She grabs a spoon and starts to eat.

I say again, how would you feel

If you had made this lovely meal

And some delinquent little tot

Broke in and gobbled up the lot?

As ever, Blake’s pen, charcoal, and watercolor illustrations are uproarious, and they appear here more often than in the author’s and illustrator’s lengthier collaborations in Dahl’s novels, but the frequent images will not make this easier for younger kids — these twisted versions are best for middle-grade readers.

But when you’re at a point where you can appreciate deviations from what you know and even a bit of comedic violence in the name of exaggeration, these are awfully fun to read aloud and cackle over together.

I hope you and your families are safe and well, reading.

Sarah

Not okay not okay not okay. So grateful you and your babies are safe. My heart is still in my throat. Thank you for this wonderful list — your example of persevering by turning to creativity and community in the wake of violence is the higher and holier way. Bless you.

I cried reading this. I am grateful, and terrified. Sadness and so. much. anger. And you still managed to write something beautiful. Thank you for your words, I am glad your babies are safe, and sorry they and you have to deal with the aftermath.