Good morning! We’re having a mini heat wave here (45 degrees yesterday; whaaaat?! I walked to pick up my kids from daycare on February 23rd with NO gloves and NO hat and NO scarf. When we got home my husband was wearing shorts.) I hope wherever you are, there’s some warmth to be found, outside or in, literally or figuratively, even if you have to work a bit to find it.

ICYMI: I sent out Part 1 of this special spotlight on folk and fairytales last week. In it I wrote (a lot) about the philosophy behind reading these types of stories to children and why I believe this genre is so important. (Research makes me inordinately happy.)

Let’s jump back right back in.

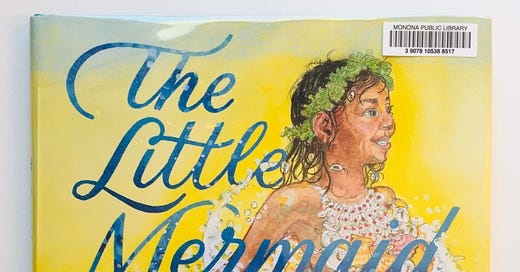

The Little Mermaid by Jerry Pinkney (2020)

Honestly, if you see a book by Jerry Pinkney, just buy it — you can never go wrong with one of his titles, and his brand-new reimagining of this Hans Christian Anderson story is no different. Here the reader meets Melody, the youngest mermaid in her family, a mer-girl full of curiosity and creativity, not content to merely sing in the choir with her sisters. Though she is aware of the dangers of the Sea Witch, “who had been cast out of the kingdom [and] would someday seek revenge,” one day she follows her guardian, a sea turtle, to the surface, where she spots a friend, a figure with “two sticklike legs” — a human! This is where Pinkney’s decision to change both the original and the Disney versions of the story (one where the mermaid ends up dying, the other where she ends up married to someone who never struck me as all that interesting or worthy) is most refreshing and appreciated — Melody strikes a devil’s bargain with the Sea Witch in order to make it up to land, and though there are great challenges to overcome and a heartbreaking decision to make before the end (which may be happy or sad, depending on your interpretation), all this is done for a friend, not a man. (At several points during the repeated reading of this my 6 and 4yo both pipe, “That isn’t what happens!” which as far as I’m concerned is just fine.) Add to this Pinkney’s truly immense talent as an illustrator — you’ll never be disappointed by his work in this regard, but in this title he has outdone himself with pencil and watercolor images that are absolutely stunning — and you have the best new fairy tale to be found.

In a long note at the end of the book, Pinkney explains the draw of “the mermaid’s inquisitive nature — her overwhelming need to dare to wonder,” and his desire “to reinvent the tale in a way that might speak more directly to today’s young readers.” Well, mission accomplished, Mr. Pinkney. (Do not miss this one.)

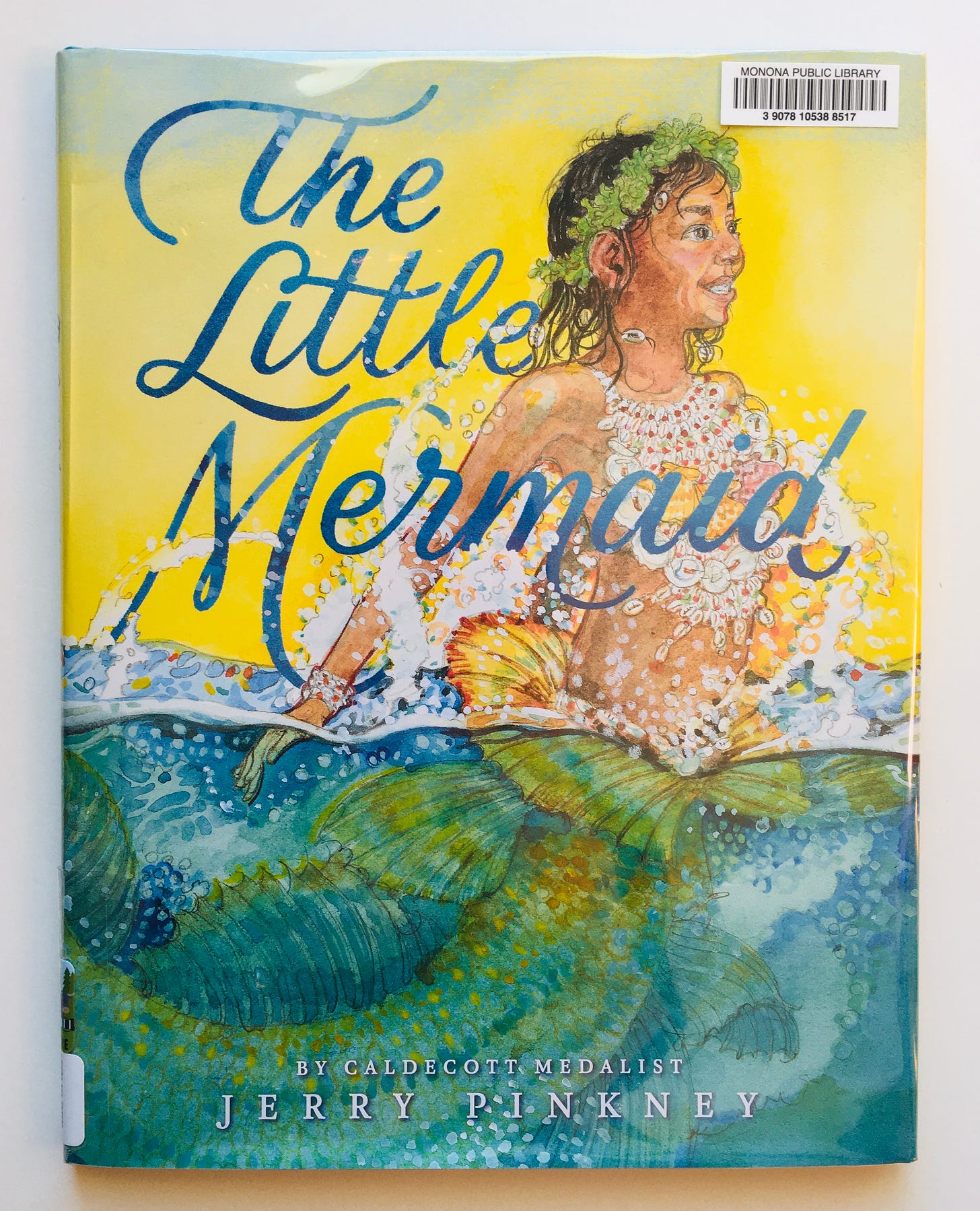

Hansel and Gretel, retold by Rika Lesser, illustrated by Paul Zelinsky (1984)

Given how well-known this story is, I’ll save the recap and go straight to my basis for recommending this title: Lesser’s captivating retelling coupled with Zelinsky’s remarkable, beautiful paintings is a match made in heaven. Zelinsky is wildly talented at what he does (and has won the awards to show it) but this, along with his version of Rapunzel, are in my opinion his best books (not just fairy tales — books, period). There are some scarier-than-usual images here — the witch grabs Hansel from bed to put him in a cage outside; you actually see the witch in the oven after Gretel shoves her in — so it might be best to preview this one first if you have a sensitive child. But if you can get it, do— it won the Caldecott for the reason books win the Caldecott*: it’s astoundingly good.

*Fwiw the Caldecott Medal is awarded for illustration; the Newberry Medal is awarded for writing. Both are annual honors from the Association for Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library Association.

Anansi Does the Impossible: An Ashanti Tale retold by Verna Aardema, illustrated by Lisa Desimini (1997)

There are a handful of titles out there about Anansi* — a trickster spider, sometimes depicted as a god, who is the hero in many tales told by the various peoples that live around the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa, who has also migrated on occasion to both Caribbean and African American folklore. But I especially love this one from Verna Aardema, in whose capable hands the figure of Anansi comes alive as only he can. Here, Anansi is tired of the fact that “all folktales were owned by the Sky God,” and heads up a mountain to buy them back. The Sky God refuses, but sets as his price three impossible tasks — if Anansi can bring the Sky God “a live python, a real fairy, and forty-seven stinging hornets.” Sure, okay. Anansi heads home to confer with his wife, Aso, who is cautious and wise. Together they hatch three clever plans to complete the tasks, and three times they succeed — the small once again triumphing over the big.

Anansi is always portrayed as some combination of rogue and wise, but what sets this particular title apart is Aso’s role — she is the one who comes up with the solution to the problem of solving each task, and without her Anansi, who performs the physical feats of daring, would never pull off any of it. Aso is intelligent — the real brain against the Sky God’s brawn — and not merely a shrewd advisor: she is an equal partner to Anansi, and as such, they truly share their success.

Desimini’s oil paint and cut-paper illustrations add visual interest with their bright, even unusual images (how one can capture a spider’s facial expression with bits of paper is beyond me, but she has done it to great effect). Matched with Aardema’s prose, this team fully communicates Anansi’s trickster nature along with something else rather more important: Anansi is beloved by children for being a mischief maker, and, I think, for being a rare character to whom they can easily, immediately relate: when you’re small you don’t often get the chance to best the bigger folks, and Anansi does it every time. That’s hopeful, and often funny, and always satisfying.

*I also recommend A Story, A Story by Gail E. Haley; Anansi and the Magic Stick by Eric A. Kimmel (he has several other Anansi titles); and our favorite, The Adventures of Spider: West African Folktales retold by Joyce Cooper Arkhurst, a collection that includes six pourquoi tales that are wonderful for preschoolers-early elementary

The Pied Piper of Hamelin retold by Robert Holden, illustrated by Drahos Zak (1997)

Told in short rhyming verse, this story of a 13th century town that called in a rat-catcher to help them with an infestation problem, refused to pay him, and lost all their children when he hypnotized and stole them away has scared me since the moment I watched it as an episode of Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre as a young child in the 80s. Imagine my horror when, upon reading this (again and again and again) with my 4yo who loves to scare herself — which Zak plays into with his creepy and grotesque illustrations to perfect effect — I looked into it further and discovered that it’s possibly a true story. There are other good renditions of this tale out there (see Sara and Stephen Corrin’s and Michael Morpurgo’s titles in my list of Everything Else, below) but there is something extremely satisfying about this one. Since it is told in verse what is actually happening in the story is somewhat subtle — it took many questions and much conversation before said 4yo really understood that the Piper took the children — which means that it rewards repeated reading (win!) It’s not always easy to pull off an entertaining telling of a less popular tale — Holden’s condensed prose combined with Zak’s formidable talent just really works.

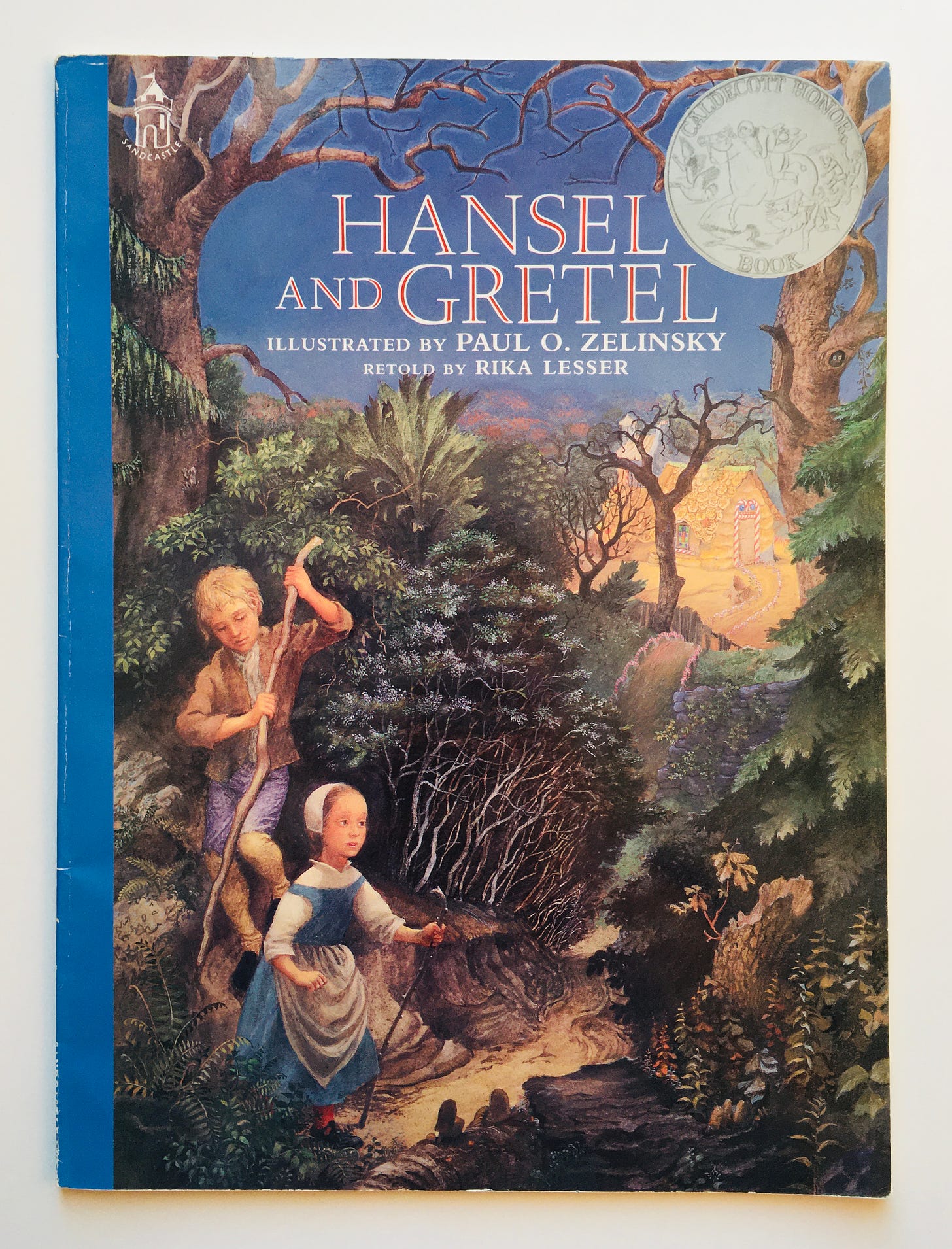

The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, illustrated by Bernadette Watts (1995)

When I first encountered this title several years ago I was unfamiliar with the Grimm’s story, “The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids,” especially how it differs from “Little Red Riding Hood” (purported to be written by Charles Perrault for the court of King Louis XIV, who directly explained that the moral of his story was intended to warn young women of the dangers of strange men) or “Little Red Cap” (collected by the Brothers Grimm, but also sometimes mixed up along the way with “Little Red Riding Hood”). But, though it’s similar in one major respect — there is wolf who intends to feast upon relatively defenseless creatures using trickery and disguise — it is, really, an entirely different story. In it, an Old Mother Goat warns her children of the dangerous wolf who will want to come inside and eat them up while she is away in the woods — and, predictable old fellow that he is, the wolf appears and attempts to do just that. Eventually he succeeds, eating up all the kids but one, who is discovered inside a grandfather clock by his mother upon her return, and together they go out to rescue the others (by cutting open the wolf’s belly while he sleeps to release the kids, filling him up with rocks, and sewing him back up again), while the wolf, upon waking, falls down a well and dies. (Honestly, even as an adult, I often feel satiated by the justice of fairy tales.) (And — Perrault’s motivations aside — sometimes I think of a Germanic mother once upon some centuries ago, coming up with a frightening tale about a wolf who will eat little children if they don’t listen, and I chuckle.)

As I mentioned last week, Watts is highly accessible, both in terms of her choice of tales and her style, to the youngest crowd. This is a simple story simply told, but done oh-so-well.

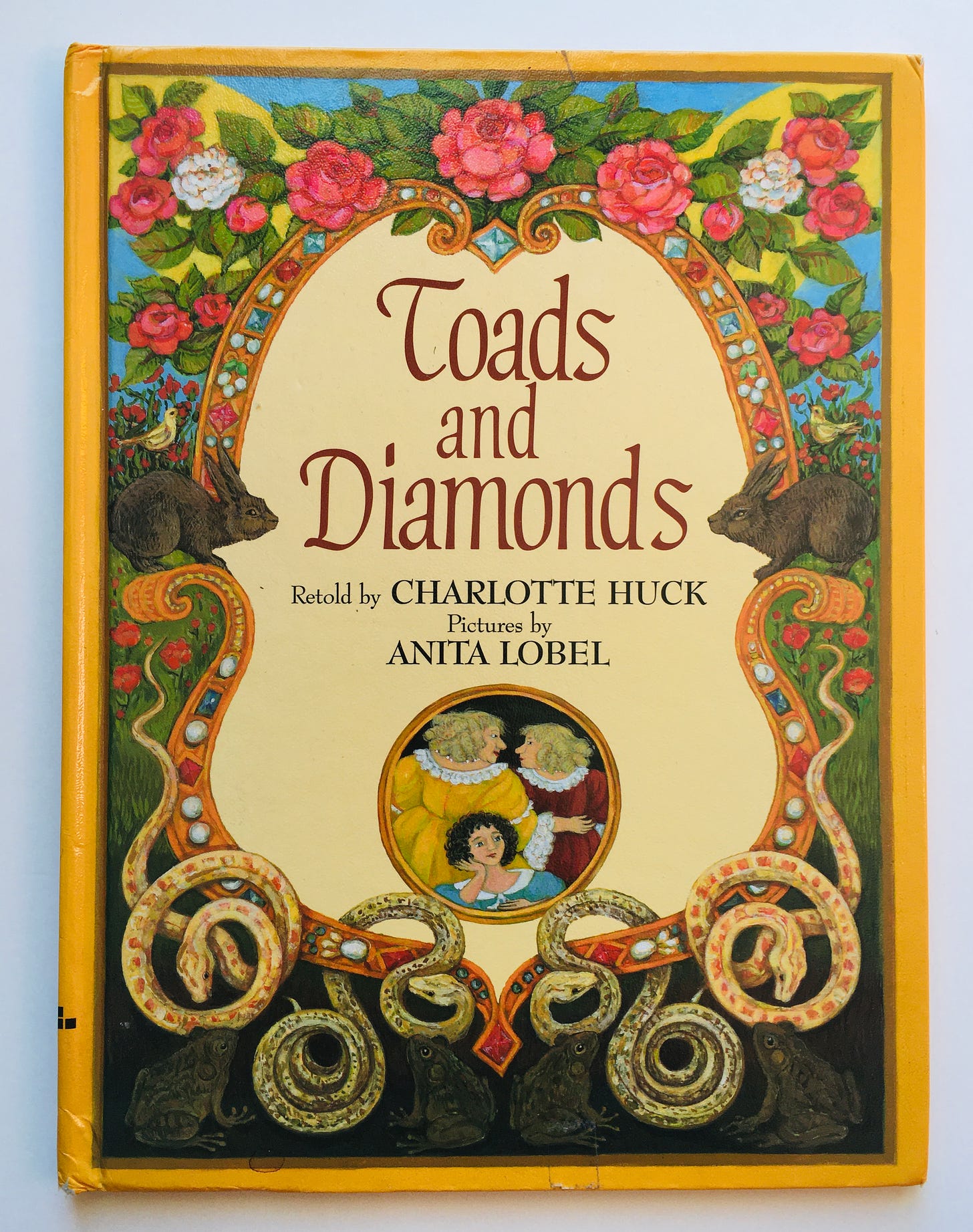

Toads and Diamonds by Charlotte Huck, illustrated by Anita Lobel (1996)

Originally written by Charles Perrault, this story of a good-hearted stepdaughter who is treated like a servant has some similarities to Cinderella, but there is enough difference here to make it a fresh tale. When Renée is one day sent to a well, she runs into an old woman and gives her water. For her kindness, the old woman blesses her with the gift of a jewel or a flower coming out of her mouth whenever she speaks. When Renée’s stepmother sees this, she sends her own daughter to the well — of course, this daughter is unkind to the old woman (who by now has taken other guises, as she’s a magical being), and her punishment is for a toad or snake to fall from her mouth whenever she speaks. The dichotomy between good and bad is extremely cut-and-dried here — Renée’s compassion and selflessness is rewarded, her step-sister’s nasty and uncharitable heart is punished — there is no nuance whatsoever, though Huck’s retelling is well-written and Lobel’s illustrations are as masterful as ever. It’s an example of what Bruno Bettleheim explained as “symbols of psychological happenings or problems” rather than reality and that’s okay — the justice, along with the whole story, is gratifying.

A category of her own: Cinderella

Cinderella by K.Y. Craft

Adelita by Tomie dePaola

Cinderella by Paul Galdone

The Golden Sandal by Rebecca Hickox (our favorite Cinderella tale after The Rough-Face Girl, which I reviewed in Part 1)

Moss Gown by William H. Hooks

The Way Meat Loves Salt: A Cinderella Tale from the Jewish Tradition by Nina Jaffe

Cinderella retold by Barbara Karlin

Yeh-Shen: A Cinderella Story From China by Ai-Ling Louie

Cinderella by Charles Perrault, illustrated by Roberto Innocenti

Cendrillon: A Caribbean Cinderella by Robert San Souci

Raisel’s Riddle by Erica Silverman

Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters by John Steptol

Interstellar Cinderella by Deborah Underwood (I love Cinderella as a mechanic!)

(If you want a huge list of Cinderella titles, the ALA has an excellent list of multicultural ones.)

Everything else:

The Princess and the Pea by Hans Christian Andersen, illustrated by Maja Dusíková

The Wild Swans by Hans Christian Anderson, illustrated by Gordon Laite (a Little Golden Book)

The Emperor’s New Clothes by Hans Christian Anderson, illustrated by Virginia Lee Burton

The Nightingale by Hans Christian Anderson, illustrated by Jerry Pinkney

The Ugly Duckling by Hans Christian Anderson and Jerry Pinkney

A Frog Prince by Alix Berenzy

The Crane Wife by Odds Bodkin

Beauty and the Beast by Jan Brett

The Pied Piper of Hamelin retold by Sara and Stephen Corrin

Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood Story from Africa by Niki Daly

Why the Sun and the Moon Live in the Sky by Elphinstone Dayrell

Puss in Boots by Paul Galdone

Rumpelstiltskin by Paul Galdone

Tattercoats by Margaret Greaves

Snow White by the Brothers Grimm, translated by Paul Heins (illustrator Trina Schart Hyman’s work is generally dark but this title more so than usual — my sensitive 6yo has only been able to handle it this year, no sooner)

Little Red Riding Hood retold by Rebecca Heller (a Little Golden Book)

The Sleeping Beauty retold and illustrated by Trina Schart Hyman

The Fisherman and His Wife by Rachel Isadora

The Twelve Dancing Princesses by Rachel Isadora

The Wild Swans by Susan Jeffers

The Emperor’s New Clothes by Naomi Lewis

Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle by Thomas Locker

Thumbelina by Sylvia Long

The Crane Maiden by Miyoko Matsutani

Baba Yaga and Vasilisa the Brave by Marianna Mayer (there are some extremely scary illustrations here so I recommended previewing first)

The Emperor’s New Clothes by Sindy McKay (this is a well-done shared reading title)

La Princesa and the Pea by Susan Middleton Elya

The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Michael Morpurgo

The Town Musicians of Bremen by Gerda Muller

Kate and the Beanstalk by Mary Pope Osborne

Bearskin by Howard Pyle

The Twelve Dancing Princesses by Jane Ray

Rapunzel retold by Barbara Rogansky

The Bearskinner: A Tale of the Brothers Grimm by Laura Amy Schlitz

The Elves and the Shoemaker by Eric Suven (a Little Golden Book)

Mother Holly by Bernadette Watts

The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde, illustrated by Jane Ray

The Bremen Town Musicians retold by Brian Wildsmith

The Emperor and the Kite by Jane Yolen

Of special note: audio

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the exceedingly excellent podcast, Family Folktales from the Nashville Public Library. The narrator of each episode, Susan Poulter, is a librarian who reads almost (but not entirely) exclusively from Andrew Lang’s coloured fairy books, which I mentioned last week. We have listened to many children’s story podcasts over the years — none even come close to this one. Every time we get in the car to go anywhere further than daycare my 6yo asks, “Can we listen to my favorite stories, please?” Thus proving to me that not only does “reading up” — the idea that kids can listen to books and stories far above their reading level and should regularly be exposed to this, as it builds vocabulary, increases comprehension, and improves listening skills (how good are your listening skills? 🤔 ) — work, it’s enjoyable as all get out.

We’ve also recently discovered (and become fairly obsessed with) storyteller Heather Forest’s audio folktales, namely Tales From Around the Hearth: Musical Folktales for Children. My most accurate description of her work is “stories with moments of song” — they’re quite fun and we’ve all loved listening to them (and then singing bits and pieces later at full volume, because I live with two small but mighty opera wannabes). Forest’s eight storytelling albums (some of which are pure narrative without music) are available to stream on Amazon Music and Spotify, or to purchase as cds/digital downloads on her website.

That’s all from me on folk and fairy tales for the time being. From now on, as I come across them and want to share, I’ll include them in normal weekly issues (along with the many fantastic and fun alternative tellings and parodies I’ve been harping about avoiding until children know the originals).

As I mentioned last week, I created a list on my Bookshop.org storefront called Folk and Fairy Tales for you, in you’re in the market for some fresh titles. There are so many good ones to choose from.

I greatly enjoyed putting together this two-part Spotlight On issue. Thanks for your inbox space, time, and attention — it means the world to me 💜

Happy (reading) ever after!

I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you make a purchase through my storefront.