A Fable for Fall: The Bear That Wasn’t by Frank Tashlin

Can we read? No. 113: From guest writer Dana Gaskin Wenig

Since March of this year, Dana Gaskin Wenig has taken my place in your inbox to share her own extensive knowledge of, experience with, insight into, and love of children’s literature. Today is her final post.

If you’d like to read all of Dana’s previous posts, you can find them here:

Thank you, Dana 🙏 for being Can we read?’s first-ever guest writer, for all the fabulous titles you’ve introduced us to — or reminded us about — and for helping me carry the load of this newsletter this year. I’m grateful for your contributions!

Here’s Dana…

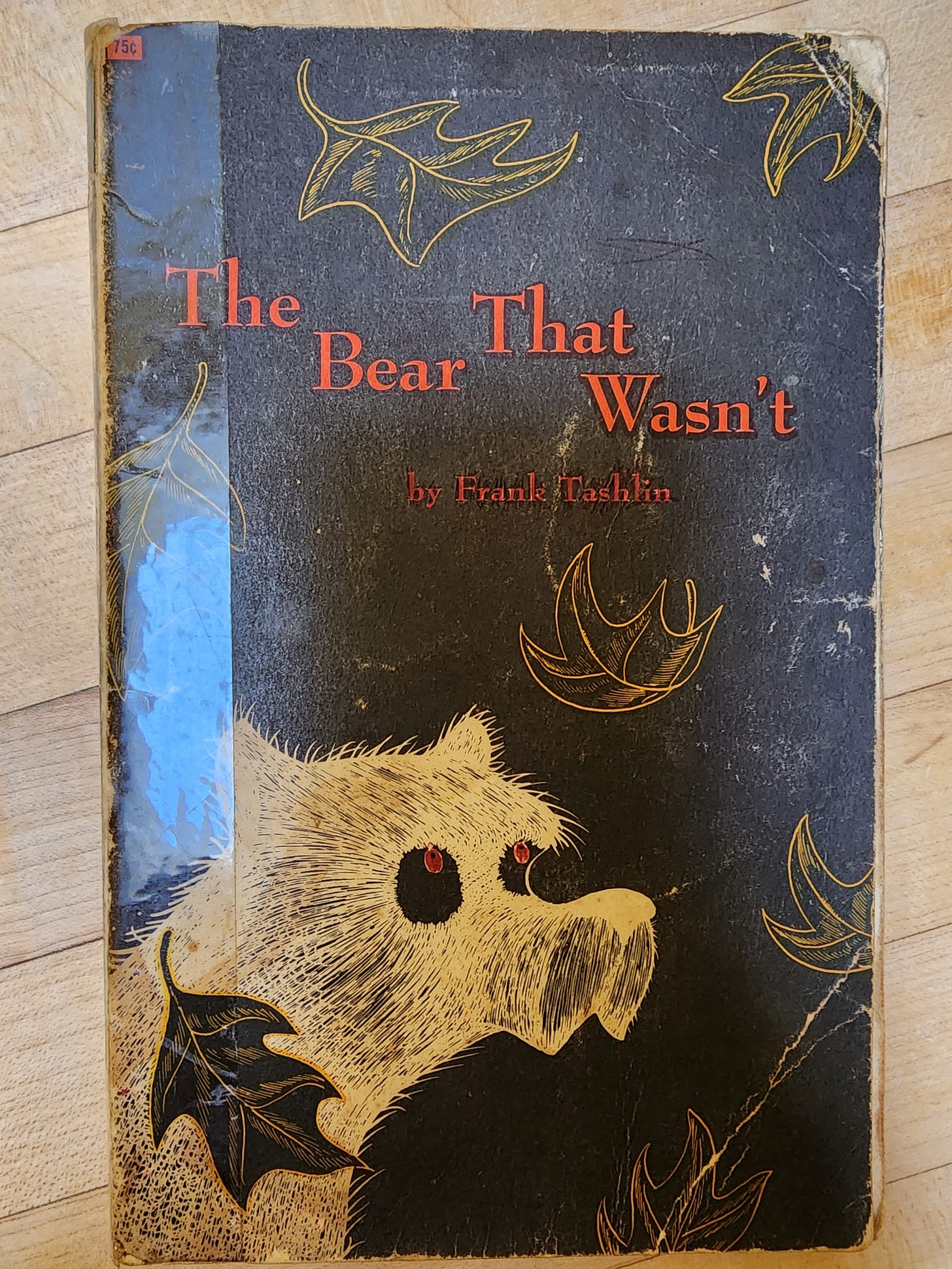

A Fable for Fall: The Bear That Wasn’t by Frank Tashlin (1946)

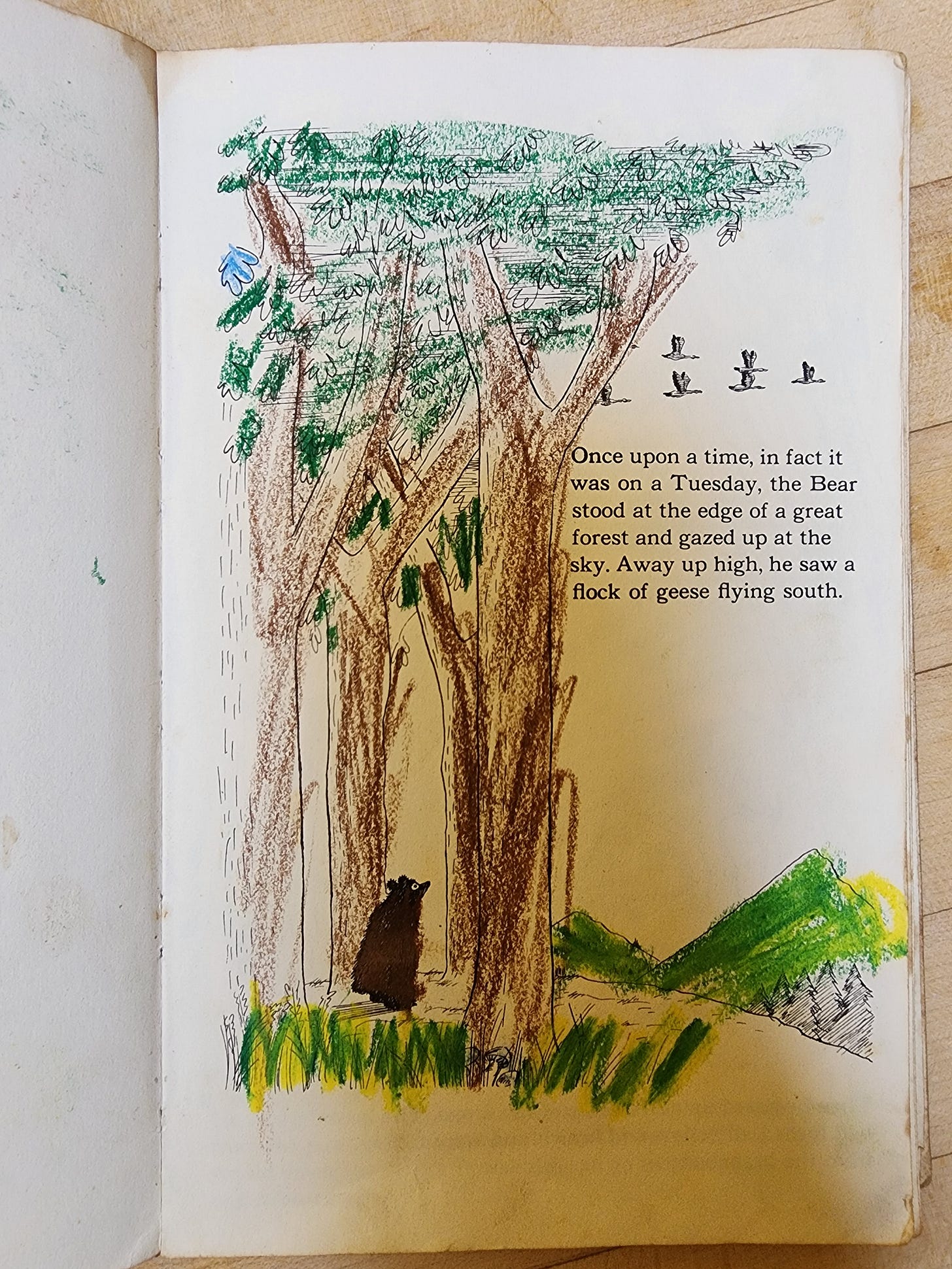

Let me tell you a story. Here we are on the first page. A Bear is standing among tall trees. Mountains and more trees are visible in the distance. Above him — wait, let me step aside so Frank Tashlin can take it from here:

Once upon a time, in fact it

was on a Tuesday, the Bear

stood at the edge of a great

forest and gazed up at the

sky. Away up high, he saw a flock of geese flying south.

In concert with the fact of falling leaves, the Bear realized that it’s “time to go into a cave and hibernate.” So far, so good. Our Bear is in tune with the cycle of the seasons and he is an animal who knows what to do at what time.

Meanwhile, “a lot of men with steam shovels and saws and tractors and axes… steamshoveled and sawed and tractored and axed all over the place” and built a “great, big, huge factory, right OVER the TOP of the sleeping Bear’s cave.”

“And then it was SPRING again.”

When our Bear wakes up, he walks toward what he thinks is the mouth of the cave and finds himself climbing stairs. He walks “out into the bright spring sunshine” to find that everything has changed. Bear tells himself he’s dreaming (disbelief) and is quickly accosted by a Foreman who tells him to “Get back to work!” Quietly and calmly the Bear says, “I don’t work here. I’m a Bear.” (This is not the last time Bear will say something like this, in fact it becomes a refrain.) And he says it in varying ways as the story unfolds.

That the humans are extremely confused about the nature of reality (more so at each level of the corporate hierarchy) is hilariously funny. We know that the Bear is a Bear, but the Foreman and the General Manager and the Third Vice President and the Second Vice President and the First Vice President and the President all tell the Bear that he is not a bear, but “A silly man who needs a shave and wears a fur coat.” This is such a successful device for immediately making common cause with the reader. We know something almost no one else in the story knows, and we are firmly on the side of the Bear.

The progression from the Foreman to the General Manager, from the General Manager to the third, second, and first Vice Presidents, and finally to the President himself (each level of hierarchy boasting a higher number of perfectly matching secretaries, only seen from the back, and more and more decorated garbage cans) carries a lot of weight for this story, though the illustrations are obviously from an earlier time. Some readers may wish to create a discussion around the fact that every member of the corporate hierarchy is white, that all the people in power are men, and that we never see the faces of the secretaries.

The Bear is steadfast in his understanding of himself (something we can all use a little dose of). He knows who he is and he’s not afraid to say so. He speaks out over and over again, stating his identity in the face of authority after authority, refusing to conform (inside himself) with what everyone around him expects. Finally the President decides to convince the Bear (using gaslighting and peer/social pressure) into believing he’s not a Bear by having other bears tell him he’s not a bear. And so, the whole group takes a road trip, from the Foreman to the President (with the Bear, of course) to the nearest zoo and circus, and the bears in the zoo and the bears in the circus can’t believe in a free Bear, so they join in, saying, “You’re not a Bear, you’re just a silly man who needs a shave and wears a fur coat!” To which the Bear replies, “But, I am a Bear.” (He really doesn’t waver.)

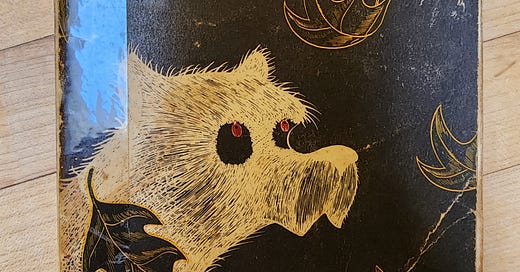

I judge the value of a children’s book in proportion to the amount of damage it has survived. By that measure, The Bear That Wasn’t was my favorite book as a child. My copy, which I inherited from a shared library, is a Dover edition printed in 1962. The white lettering on the cover has been colored in with red pen, the spine is held together with clear packing tape (as are the first two pages), and in rereading it this past week, I see that the last two pages need the same treatment. The corners of the little paperback are bent (perhaps chewed) at the edges, pages have received libations of food (or drink?), and many have been mistaken for the pages of a coloring book, featuring work in both crayon, colored pen, pastels, and colored pencil. (I’m not generally in favor of writing in books, I don’t even mark up study books, but this one has become a work of art.)

Frank Tashlin wrote and illustrated three books, the most popular being The Bear that Wasn’t, and said, in an interview with animator Michael Barrier in 2004: “It was kind of precious and special to me.” It was so precious to Tashlin that he wouldn’t allow Disney to animate it, or anyone else who asked, until Chuck Jones. Jones had done a beautiful job animating “The Dot and the Line” (1965), so Tashlin agreed. He came to regret it the moment he saw the film. Jones had “ruined” it by showing the Bear holding a cigarette in an early scene, undercutting the entire concept of the book (that he was a Bear, not a man). Tashlin said, “I almost cried. I never talked to Chuck about it, I've never talked to him since. It was a terrible thing.”

Tashlin was known best for his work in animation and filmmaking but also as a cartoonist who worked for Warner Brothers, Disney, and Columbia Pictures (among others), and never for very long. I noticed he didn’t stay anywhere long, often leaving after arguments with higher ups. My question is: was Frank Tashlin a Bear who kept getting confused for a “silly man who needs a shave and wears a fur coat”? Did Frank Tashlin feel like he didn’t belong in the animation factory? Did Tashlin (or Tish Tash as he was known) need to be free?

He went on to write jokes for people like Lucille Ball and the Marx Brothers and he was a screenwriter for Red Skelton and Bob Hope. He also wrote two other books for children: The Possum That Didn't and The World That Isn't, which I have yet to read. If you decide to buy someone a gift copy, the New York Review of Books published a beautiful copy. Otherwise, I’m sure you can find a less embellished copy (than mine) online perhaps here.

From the first page, and the opening line on it (which are nestled next to the trees, above the mountains, and under the geese), this book is firmly set in nature. What could be more natural than a Bear standing at the edge of a forest watching the geese fly south? There is no doubt that this Bear is a Bear. And “he knew, when the geese few south and the leaves fell from the trees, that winter would soon here and snow would cover the forest. It was time to go into a cave and hibernate.” Bear is a creature at home in the world he has always known, alert to the signs of the seasons and aware of his place.

In “Wild Geese,” perhaps Mary Oliver’s most famous poem, she closes by saying:

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

This bear knows his place “in the family of things.” All is well. Bear takes his winter nap.

The ninth page from the end of the book is a match for the first. The Bear had accepted his lot and worked in the factory alongside the humans, but the factory closes for the winter, all the men leave, and the Bear is left behind. “As he walked along, he happened to gaze up at the sky. Away up high, he saw a flock of geese flying south.” What follows, these last few pages, are scary and tender, sad and heartening, and ultimately just right.

PS: The Bear That Wasn’t is being used to help teachers build lessons that “explore identity, conformity, and authority” via the global organization, Facing History & Ourselves.

Dana Gaskin Wenig is a writer, writing teacher, and former bookseller. She lives in the Seattle area.