Rereading Stuart Little 🐭

Can we read? No. 111: From guest writer Dana Gaskin Wenig

Once a month until September, Dana Gaskin Wenig takes my place in your inbox to share her own extensive knowledge of, experience with, insight into, and love of children’s literature.

Below, find Dana’s recommendations for July.

Rereading Stuart Little

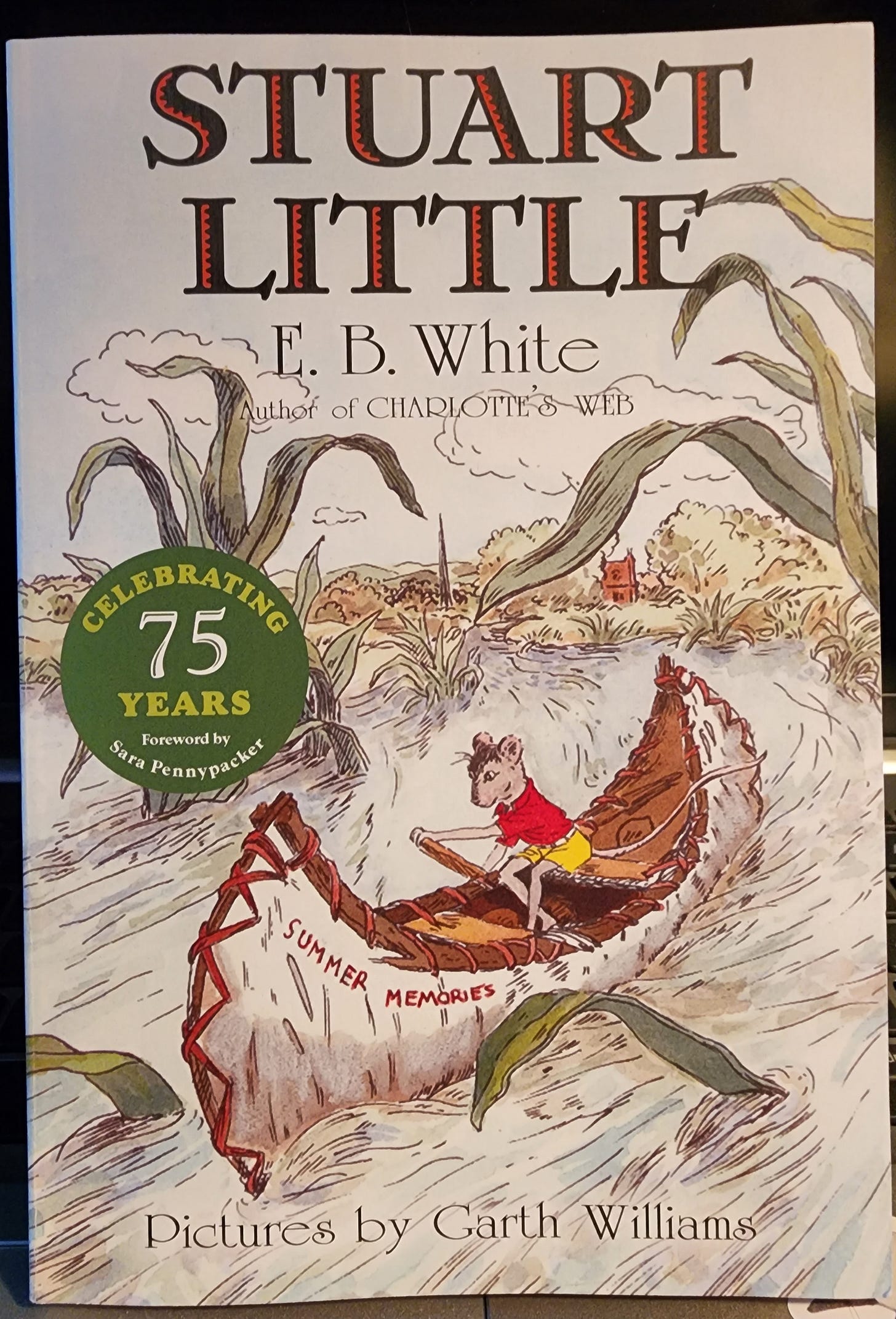

E. B. White’s Stuart Little (1945) is the first of White’s classic books for children, followed by Charlotte’s Web (1952) and The Trumpet of the Swan (1970).

It’s also the first children’s book Garth Williams illustrated (White suggested Garth Williams when he sent the manuscript to his editor). Presumably, it is also the first time a mouse was born into a human family. Williams went on to illustrate eleven books for children written by Margaret Wise Brown, including Wait ‘Til the Moon Is Full (1948), another favorite in this house, he was commissioned to illustrate the new Little House editions in 1947 (by Laura Ingalls Wilder), and his work can be seen in dozens more children’s books. His style is so much a part of White’s, Brown’s, and Wilder’s books that it’s impossible for me to think of any of these titles without seeing his kindly and finely drawn illustrations carrying the stories hand-in-hand with the words.

About the genesis of this story, White wrote to his editor:

“The principal character in the story has somewhat the attributes and appearance of a mouse… At the risk of seeming a very whimsical fellow indeed, I will have to break down and confess to you that Stuart Little appeared to me in dream, all complete, with his hat, his cane, and his brisk manner. Since he was the only fictional character ever to honor and disturb my sleep, I was deeply touched, and felt that I was not free to change him into a grasshopper or a wallaby.”

Thank goodness.

Stuart, born into the human family of Mr. and Mrs. Little and their son George, does not arrive as an infant but “could walk as soon as he was born.” His mother responds by quickly setting aside the baby clothes she had prepared for his arrival and making “him a fine little blue worsted suit with patch pockets in which he could keep his handkerchief, his money, and his keys.” Stuart, being so small, turns out to be very helpful to his family for things like rescuing his mother’s ring when she loses it down the drain, finding lost Ping-pong balls, and working stuck piano keys when his brother is playing (his brother’s idea). And though they “never quite recovered from the shock and surprise of having a mouse in the family,” Mr. and Mrs. Little are very sensitive to their mouse son’s feelings and the family works together to change the words of nursery rhymes and poems to avoid references to mice that could be seen as “belittling.”

White came to writing books for children by way of being a reporter between 1921 and 1924, writing advertising copy, working on a fireboat in Alaska, and writing for both The Seattle Times and The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (I’m writing this from just north of Seattle proper). He published books of poetry, humor, collections of the columns he wrote for Harper’s Magazine, and political editorials, all before Stuart Little came to him in a dream. He is also the “White” of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style (1959), the famous book on grammar originally published by William Strunk, Jr. in 1918.

Stuart Little is one of those rare books that doesn’t fall into the trap of moralizing. It is a story about adventure, about love, and about courage. I suppose one could also argue that it’s a story about being the different one in a family, but I never thought of it that way when I was growing up — it’s only now, looking back, rereading, that I see how that is also part of the story. Funny that I never questioned how a small mouse like Stuart could have been born to a human family when I was a kid, even though that difference and the acceptance of it is addressed in the story.

This book joins two of the books I reviewed last month: Stuart is a small person in a big person’s world (like the Clock family in The Borrowers) and Stuart’s great love is for Margalo, who is either a “wall-eyed vireo” or a “young wren,” depending on whether you ask George or Mr. Little. And like in the Fairy Tales of e. e. cummings in which a house falls in love with a bird and an elephant falls in love with a butterfly, Stuart loves his friend Margalo simply and wholly. He devotes himself to her wellbeing and safety over and over again, which she reciprocates.

Adaptations of Stuart Little include an audiobook, three movies (very loosely based on the book), an animated series that came out in 2003 on HBO, and multiple video games.

For me, the most interesting adaptation is “The World of Stuart Little,” (1966) an episode of NBC’s Children’s Theater with Johnny Carson reading an abridged version of the book. The music is quite warbly by now (it’s available on YouTube in two parts), but the video is charming and provides a sense of New York City in the 1960s that makes it a pleasant addition to the book. It opens on a seagull winging over the Atlantic, gives a bird’s-eye view of the Statue of Liberty, then downtown Manhattan and Central Park, before it homes in on the Little’s home. The episode was nominated for an Emmy and won a Peabody Award.

I have spent little time on the character of Snowbell the cat because I do not like him or his friend, the Angora. You’ll see why. Snowbell is a troublemaker who, no surprise, has it in for Stuart (in a lazy, manipulative way), and for Margalo. Despite that, this story is safe to read to younger or more sensitive listeners. And the adversity Snowbell brings to the mix serves to send Stuart off into the world on his own with the help of his friend the dentist and the kindness of many more people down the road.

In rereading Stuart Little over the past few days, I remembered that as a kid, I often carried a small purse with me that held a (stuffed) mouse and additional items that would be useful to a mouse. One day as I was crossing a river by way of a swinging footbridge with my mother, I fell and lost hold of the strap of my little purse. My companion mouse and their special items fell over the edge into the river and were swept away. I quickly told my mom I’d lost my purse, and we ran downriver to search for it. I still regret that we did not find it. I can only hope that my lost mouse found help and companionship on their way exactly as Stuart Little did in his various adventures. Stuart sailed a model boat on a lake in Central Park, fell into a garbage truck, and floated out to sea on a barge (and was rescued!), was a substitute teacher for a day, and traveled to find his lost friend on his own.

I chose to review this book without thinking about how firmly it is set in New York City or putting that together with the fact that my New York City aunt had passed away a few days ago at 102 years old. It is because of my New York aunt that I know Central Park and remember model sailboats moving across a pond in that park, because of her that I know the dusty smell of the 19th floor of an apartment building at the corner of Central Park West and 84th in the mid-60s, and because of her that the Johnny Carson episode mentioned above fills me with nostalgia.

I know 102 is a long run, but I will miss my New York aunt who loved animals perhaps more than she loved people; I’m here to say that Stuart Little’s 78 years is a long run too, and I recommend you read this beautiful classic book in the original at your earliest convenience.

Dana Gaskin Wenig is a writer, writing teacher, and former bookseller. She lives in the Seattle area.

Stuart Little video games!? Thanks for sharing. I need to revisit this book and check out the 1966 adaptation!

What a beautiful review, and ultimately tribute, to your aunt. I love how you elegantly wove history/elements of the book into your personal journey as a reader, young girl, and now adult.

I loved Stuart Little as a child and re-read it many times for the adventure of it. Funny, I blocked Snowball from my mind. I have a copy on the shelf. Time to pull it down again.