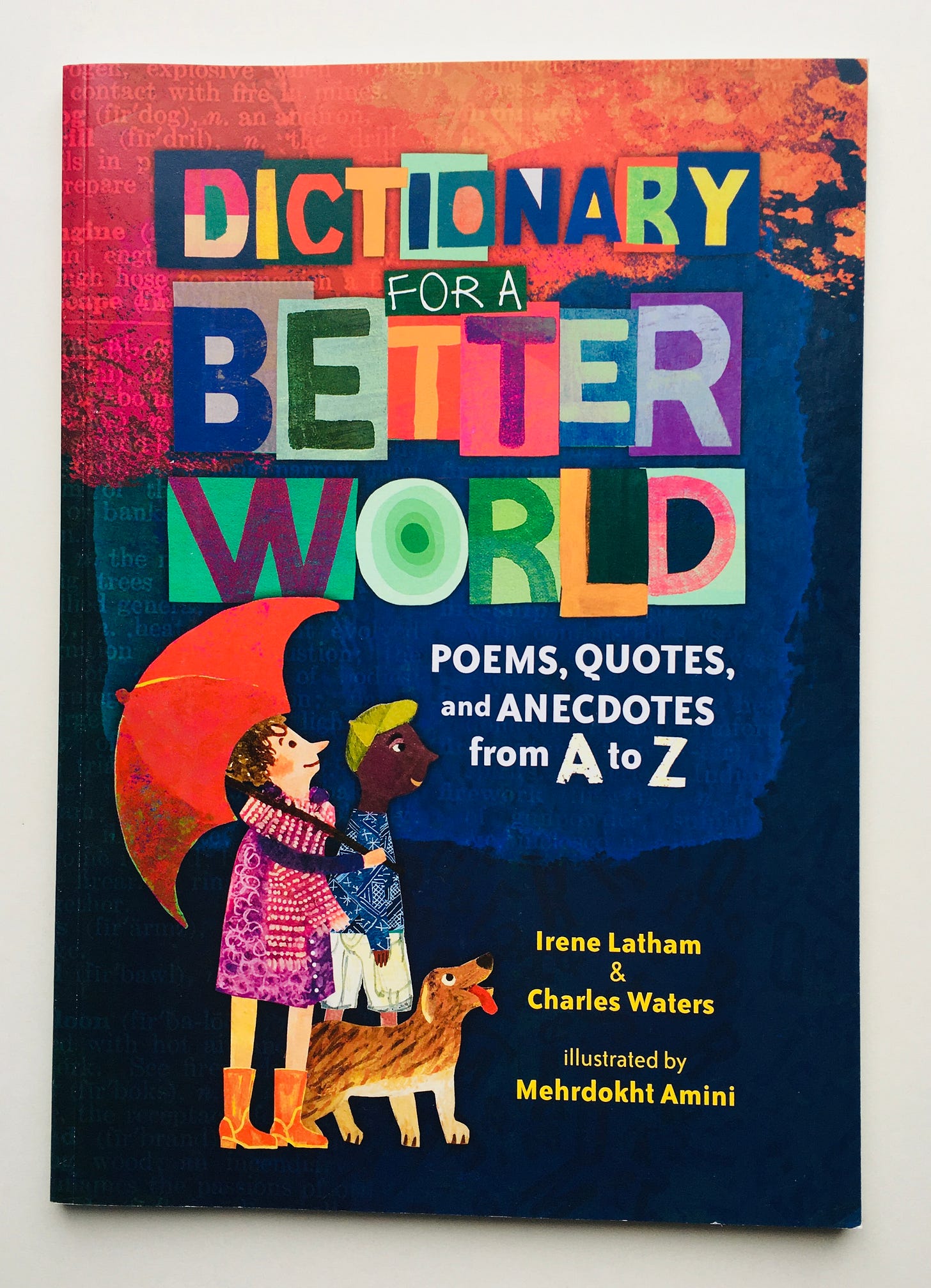

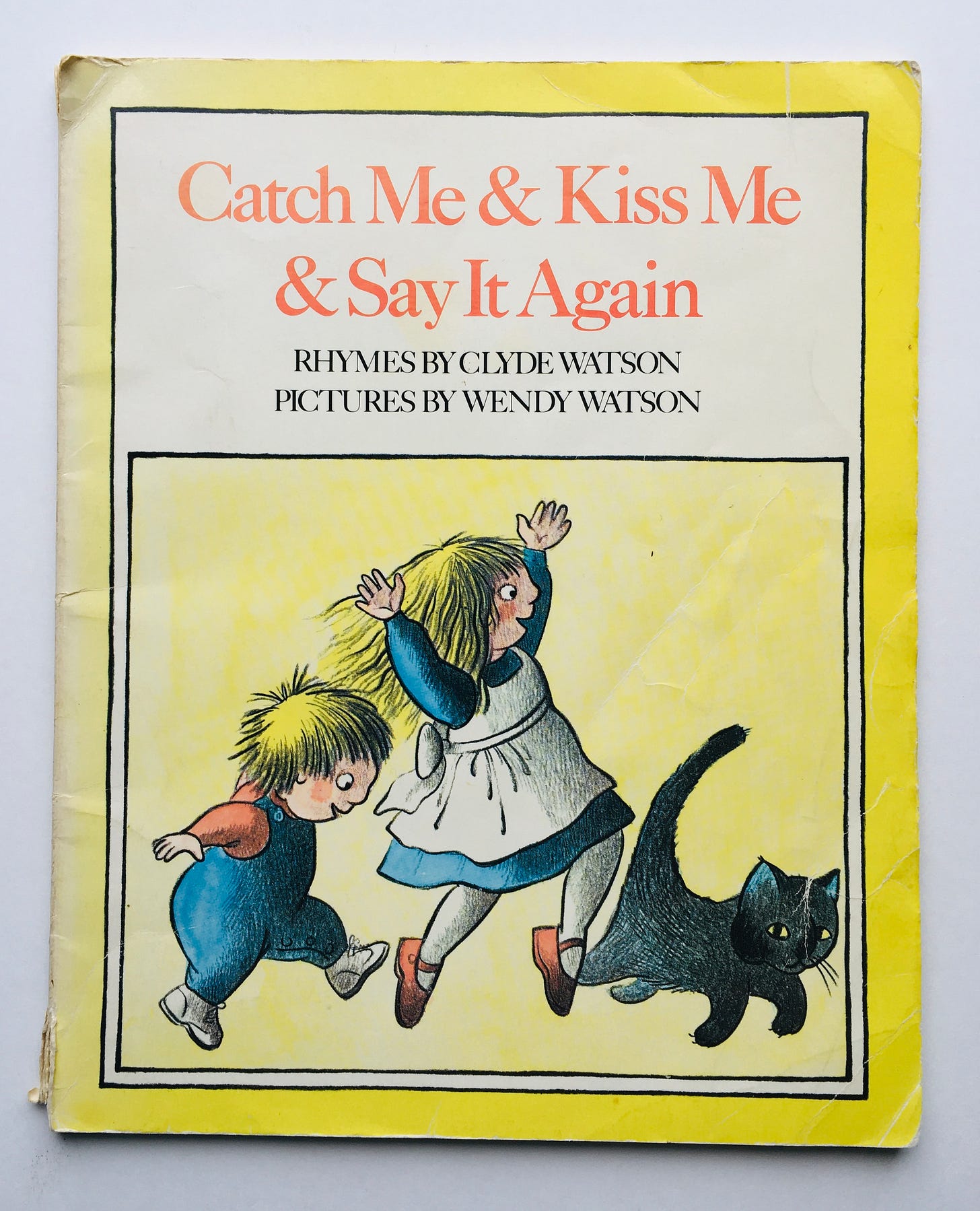

It’s easy to talk about the benefits of poetry when you’ve been a lifelong poetry lover like I have. I don’t even know quite where this love came from, though I am willing to bet that the poetry book my mother read to me regularly — Catch Me & Kiss Me & Say It Again by Clyde Watson, published in 1978 and now long out of print — had something to do with it. We can (and do) recite the title poem to one another in its entirety to this day.

If she hadn’t read to me faithfully every single night, I might have still grown up to be a reader. Maybe. But there is no doubt in my mind that I would not have loved language as much as I do.

One of my all-time favorite poets, Carl Sandburg, wrote this about poetry in the March 1923 issue of The Atlantic (back when it was The Atlantic Monthly):

“Poetry is an art practised with the terribly plastic material of human language.... Poetry is a puppet-show, where riders of skyrockets and divers of sea fathoms gossip about the sixth sense and the fourth dimension... Poetry is the journal of a sea animal living on land, wanting to fly the air... Poetry is a search for syllables to shoot at the barriers of the unknown and the unknowable... Poetry is the cipher key to the five mystic wishes packed in a hollow silver bullet fed to a flying fish.... Poetry is a fresh morning spider-web telling a story of moonlit hours, of weaving and waiting during a night.... Poetry is a pack-sack of invisible keepsakes... Poetry is the capture of a picture, a song, or a flair, in a deliberate prism of words.”

It’s all that and more, and I love sharing that with my kids.

But on a more practical level (or, at least, some people need more proof than Sandberg’s poetic testimony — I am not one of those people, which you may have already guessed), here are some reasons why poetry matters and why it’s important for children:

It helps with language development

It supports literacy skills and scaffolds emerging readers

It exposes kids to all sorts of language and vocabulary and grammar

It enhances memory

It encourages play

It offers an outlet for creative thinking and emotional expression

It’s a comfort during hard times

It’s fun

Let’s break all of these down one by one.

Poetry helps with language development

When I had a tiny baby, I remember reading and hearing a lot about how important it was to talk to her — my favorite baby book, Your Baby and Child: From Birth to Age Five by Penelope Leach, told me to talk, talk, talk to my baby constantly, narrating what I was doing, and I did. (This isn’t hard for me — once I get over my initial reticence with you, I never shut up.)

Most people know that the first three years of life are the most critical in terms of brain growth and development — everything inside that gray matter is exploding in the best possible way, including the acquisition of speech and language skills. It would make sense then that talking to your baby and reading to your baby is vital.

Poetry plays a special role because it’s so well-suited to that tiny, burgeoning brain. Nursery rhymes may only date to the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries (and were likely intended for adults, at least for awhile), but other forms of oral poetry (like Greek lyric) are thousands of years old and likely stemmed from an even more ancient oral storytelling tradition.

Another way of saying this is: humans have been using language to teach language since we first figured out how to make words with our mouths and tongues.

(By all means, continue to pour your time and energy into pureéing organic squash for your baby — no judgment; I sure as hell did — but while you’re doing that, take a minute and read some poetry out loud. It’s actually more important.)

Poetry supports literacy skills and scaffolds emerging readers

Rhyming teaches children to listen to the sounds that words are made of — the phonemes and graphemes, to get technical about it. (These are the individual speech sounds and the individual letters or groups of letters that represent the individual speech, respectively. Don’t worry, there isn’t going to be a quiz later.)

Additionally, poetry teaches kids about how to read — volume, pitch, inflection, patterns, pronunciation, all those things a reader does out loud with their voice, which eventually translates into what they hear in their head. These speech patterns help because they offer cues about what’s on the page. I have noticed this with my emerging reader, as we practice the “two voices” poems from the book, You Read to Me, I’ll Read to You: Very Short Stories to Read Together by Mary Ann Hoberman — she might not be able to decode the word at the end of the line, but because it rhymes with the one that came two lines above it, she’s better able to guess (and is more often than not correct).

In her outstanding and practical book, Reading Magic: Why Reading Aloud to Our Children Will Change Their Lives Forever (which I reviewed in issue No. 47), Mem Fox writes, “Rhymers will be readers; it’s that simple.” And it really is. She goes on to say:

Experts in literacy and child development have discovered that if children know eight nursery rhymes by heart by the time they’re four years old, they’re usually among the best readers by the time they’re eight.

Is exposing your kids to poetry automatically going to help them read? No. There are no shortcuts (trust me, I’ve looked). But it seems like an incredibly easy, low-stakes tool to ease the way.

Poetry exposes kids to all sorts of language, vocabulary, and grammar

A blog post on the Reading Partners website says it clearly:

Like any form of reading, poetry can introduce children to new words. Poetry is unique in that it typically follows a rhythm. When children read sentences and phrases that have a cadence, it introduces them to new words in new contexts.

Even though it may not seem like it, a poem that rhymes is the result of certain restrictions a poet followed during the writing process. If they want every other line of a poem to rhyme, there are a limited number of rhyming word pairs that could contextually fit in the first and third lines. For the poet, this results in surprising new connections between words. For the reader, these new connections translate to a larger vocabulary.

Time and again we have come across words in books of poetry we’re reading that have caused my children to interrupt and say, “What does that mean?” and all of a sudden we’re talking about a word that would rarely, if ever, come up in daily conversation. That’s why reading aloud (and not just poetry) is so important for kids — the number of vocabulary words kids encounter on a page, whether it’s with their ears or their eyes, is exponentially higher than the number they encounter verbally.

Moreover, poetry introduces readers to figurative language — synonyms, antonyms, metaphors, similes, analogies, puns, wordplay, colloquial expressions, and made-up words. All of these things are important parts of learning to read and being culturally literate, not to mention stimulating imagination and creativity through rich imagery and ideas.

Poetry enhances memory

I feel like this point needs zero support — in our age of distraction, who needs to be convinced that memory and retention is an important skill to strengthen?

Memorization does a couple of important things inside the brain (I’m keeping this simple because I’m neither a brain scientist nor a medical journalist): it increases the size and improves the function of memory-related brain structures and stimulates neural plasticity, which alters the brain’s neural pathways and allows for functional brain development in young children (and functional brain changes in adults — something anyone interested in preventing cognitive decline due to age should take note of).

There is another, finer point here, one I’ll admit I didn’t think of until I discovered it in an article about the benefits of memorizing poetry from Edutopia:

Students are not asked to memorize much anymore, yet many of them take pleasure in the act of repetition and remembering. They like testing themselves and realizing that they can in fact recall lines. For English language learners, many students with IEPs, autistic students, and other exceptional learners, reciting poetry is an especially powerful way to understand language and build confidence. For our kids who need small victories, mastering one poem is a welcome vindication and relief.

Poetry encourages play

Perhaps more than any other form of writing out there, poetry encourages children to play with language. Is there a more flexible container for silliness, creativity, imagination or make-believe? If there is, I don’t know it.

That begins with listening — with realizing that kind of playfulness is not only possible, but encouraged in poetry.

But then it goes further when kids are old enough to write poems of their own. Most go through their K-20 education up to their foreheads in academic writing — handwriting practice, spelling and dictation tests, five-paragraph essays, speeches, papers of all kinds. (We also do all we can to kill their love of reading, which means many of them leave their formal schooling experience without ever enjoying, or realizing the potential for enjoyment, that playing with words holds.)

If children are exposed to the idea of language as play at a young age, they are much more likely to be able to tap into that as they get older. Yes, some of them will forget, and lose it, but some won’t.

Poetry offers an outlet for creative thinking and emotional expression

Kids have a lot to say. Just ask any 6yo (six being the age when, in my experience, you simply cannot get a word in edgewise at the dinner table and must give yourself over to being impressed that one person can hold up an entire conversation, by themselves, for 20 straight minutes). Unfortunately, we don’t, as a culture, give children much room to share.

Enter poetry.

Poetry holds out a hand to children — if I am reading a poem about something, depending on the topic, it can offer an opportunity for emotional connection. Has this ever happened to you? Have you ever felt this way? How does this poem make you feel?

It can also help children reflect on their own emotions, or bring back deeply felt moments, good or bad.

(This doesn’t just apply to little kids, of course. Between the ages of 12-18 my output of — mostly horrible — poetry was colossal. Poetry is the perfect container for the volcanic emotional eruptions of teenagers.)

Poetry is a comfort during hard times

If you’ve never picked up a book of poetry when you’re heartsore or grieving, you’re missing one of literature’s great balms. If this wasn’t true, there wouldn’t be titles written for this sole purpose — books like, Bright Poems for Dark Days: An Anthology for Hope by Julie Sutherland or The Hell with Love: Poems to Mend a Broken Heart by Mary D. Esselman and Elizabeth Ash Vélez or Staying Alive: Real Poems for Unreal Times by Neil Astley (the last one has been with me for nearly 20 years).

This is why Rupi Kaur’s books are bestsellers; why people quote, or even type out entirely, Wendell Berry’s famous poem, “The Peace of Wild Things” on their social media accounts (I’ve done it myself); or, arguably, why Mary Oliver is so beloved by so many people — her poetry is both a celebration of and antidote to being a person alive in the world: comfort during hard times.

I’m not the only one who believes in this idea. In her searing memoir about her difficult childhood and its lasting effects on her life, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, Jeanette Winterson wrote a testament to the power of poetry during hard times:

So when people say that poetry is a luxury, or an option, or for the educated middle classes, or that it shouldn’t be read in school because it is irrelevant, or any of the strange and stupid things that are said about poetry and its place in our lives, I suspect that the people doing the saying have had things pretty easy. A tough life needs a tough language — and that is what poetry is. That is what literature offers — a language powerful enough to to say how it is. It isn’t a hiding place. It is a finding place.

It’s a finding place, indeed.

Poetry is fun

When I am constantly yammering on that poetry is important for children, I mean it for all of the reasons I’ve already outlined, but I mostly mean it for the reason that poetry is immensely fun.

If no other reason matters to you, read it because it’s fun.

If after all of this you’re still skeptical, still unwilling to believe you can find poetry you and your children enjoy and even relish, my recommendation is to start with poetry that you find fun.

(If you don’t want to take my word for it, okay: just see the lifetime sales figures of poets Shel Silverstein and Jack Prelutsky. I have no idea what these figures actually are but trust that they are enormous, no doubt because they both wrote poetry books chock-full of whimsy and humor.)

Ideas for your home

💡 Post a poem

Post a poem in a spot where your people have to take a second — the bathroom mirror (to read while brushing teeth), inside the door of a closet or cubby (while hanging up a coat or taking off shoes). For a little while I taped the following poem, from The Ice Cream Store by Dennis Lee (which I reviewed in issue No. 63), to a small section of wall near the tub and recited it when it was bathtime:

Chillybones, chillybones—

Who’s got the chillybones?Rub them, and scrub then,

And warm up their sillybones!

For a long time I had a Waldorf verse written on a 3x5 card tucked into the corner of a painting in my kids’ bedroom: every night, after reading books but before lights out, we’d recite this short fingerplay — whatever it was escapes me now — which they just loved. It was one final Hail Mary pass at getting the wiggles out before lying (or trying to lie) quietly and close tiny eyes. I’m not sure it did that, but it was a super simple way to end the day with poetry, which was reason enough for me.

💡 Create found poetry together

This one is as simple as it sounds, and if it comes out looking a bit like a ransom note, well, so what? Channel your inner collage-making teenager (my inner collage-making teenager lives right on the surface and comes out at the slightest provocation) and cut out words from magazines, newspapers, catalogs, junk mail (we all at least still receive junk mail) and use it like magnetic poetry to create your own poems.

I’ve found it’s easier with very young littles and pre-readers if I am the one actively seeking out verbs and adjectives, and my kiddos just cut out anything they can identify as words. (Identifying print as words is a wonderful pre-reading activity. If all they can do is snip letters, that’s just fine!) Remember the importance of playing with language? You could write a whole silly poem from a few words and a bunch of letters. The point is not to create great literature here, the point is to goof around and have fun.

💡 Poetry teatime, or poetry café

Poetry teatime (or poetry café if teatime isn’t your thing) is something I stole from the homeschool world years ago. I first heard about it from the creator of a wonderful writing and language arts program and author Julie Bogart, but it’s not rocket science. You sit down with your kids (at the kitchen table, in front of the fireplace, on a picnic blanket outside), a pot of tea (or any other beverage you want) and some treats (baked from scratch, out of a box, or store bought) and a stack of poetry books, and you read them out loud. That’s it.

If it sounds really simple, that’s because it is.

If you wonder how it can be special: try it and see.

(I first mentioned poetry teatime and how we do it, including photos, in the February 2021 issue of (How) Can we read?, which was all about our reading routines, if you want more where this came from.)

💡 Go outside

Use whatever you normally do outdoors as an opportunity to inject some poetry. What do you think jump-rope rhymes are? Get out a jump rope or jump on the trampoline. Play hopscotch and move to the beat of a poem. See who can shout out a nursery rhyme while rolling down a hill at the same time. I often recite poems while pushing my children on their spiderweb swing — we have great fun trying to time the swing to match the end rhyme.

💡 Use technology

Use a voice recording app to read poems into your phone (ones from a book, or ones you make up!) and then play them back — or let your children be the ones who do this. Kids love hearing their own voices. (This is also a good bribe when you have a reader who needs practice but doesn’t feel like reading — the incentive of hearing themselves read it back can sometimes entice them to begin, and we all know beginning is the hardest part.)

💡 Pair poetry with a picture book

For every poetry book there is a picture book tie-in, some way, some how. Let’s say you’re reading Wynken, Blynken, and Nod by Eugene Field, illustrated by Johanna Westerman — you could pair it with The Weaver by Thacher Hurd, Freefall by David Wiesner, and In The Night Kitchen by Maurice Sendak, which are all, in various ways, about dreaming and flying (or are they? 🤔 )

Especially if you are willing to flexible about what connects a poem/poetry book to a picture book, the possibilities are endless. (And maybe you don’t make this connection explicit to your children but ask them what they think. Their answers may surprise you.)

💡 Write poetry together

In March 2021, writer Jason Basa Nemec penned a beautiful article for The Washington Post, titled, “Why kids needs poetry in their lives, and how to speak their interest in it” that I cannot recommend highly enough. I wish I’d written it. (For an excellent visual walk-through of the “poetry class” he does with his young children, head over to his Instagram and watch his highlight, Poetry Class.)

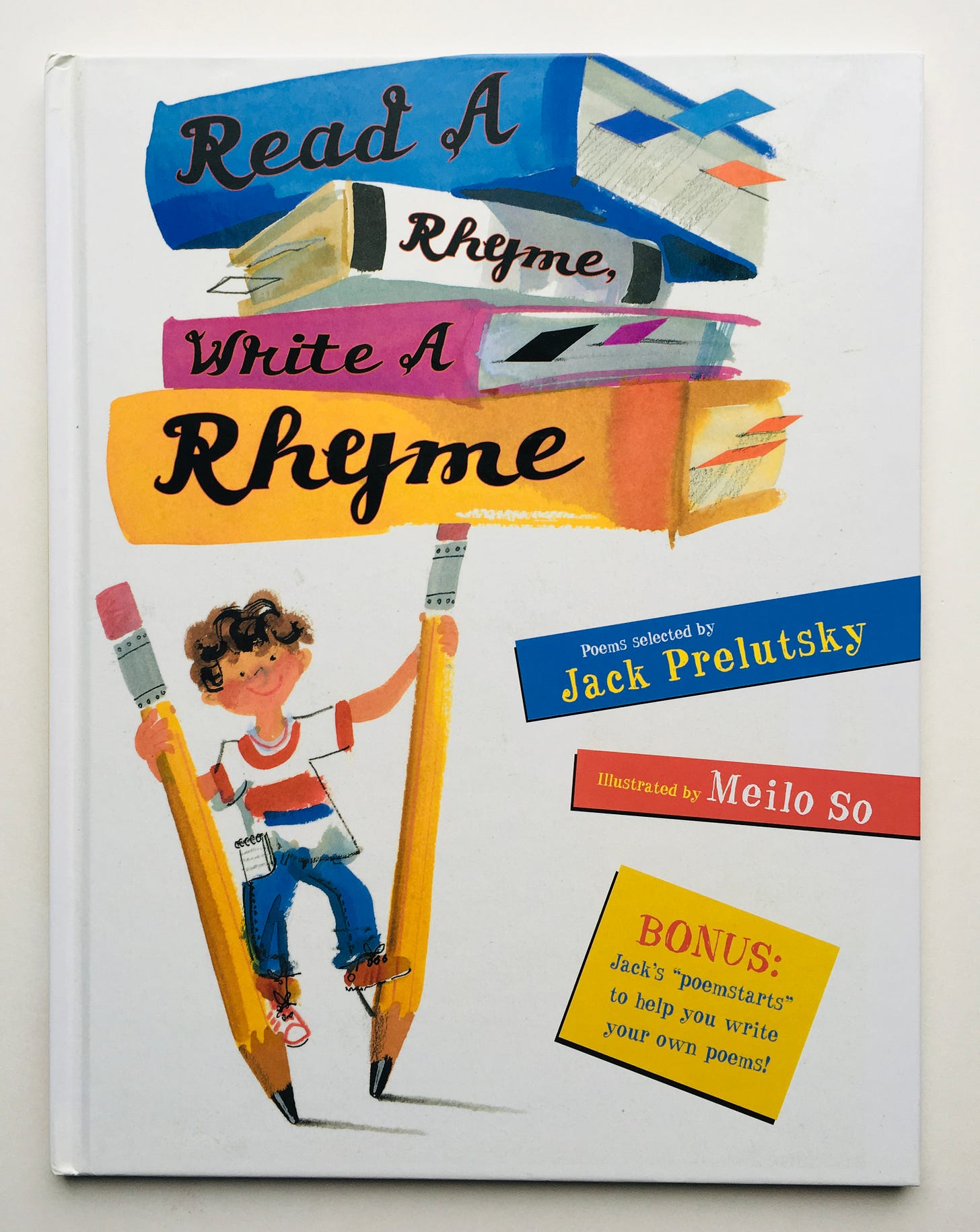

There are also books that may help. I love Jack Prelutsky’s Read A Rhyme, Write A Rhyme for its excellent selection of poems, fun illustrations by Meilo So, and truly helpful (and totally do-able!) “poemstarts” on every page, to spark poetry writing on your own.

If you want to try any of these ideas — or come up with your own — it’s okay (in fact, I encourage it) to start small. Bringing poetry into your life doesn’t have to be big or complicated! A little goes a long way, and the most important thing is to have fun.

Today’s takeaways, or some things to consider:

Are you reading poetry to the children in your life? Why or why not?

Of the reasons why poetry matters and why it’s important for children, which one(s) matter to you the most? Why?

Will you try any of the ideas I offered with your own family? Which ones? (Make a plan now!)

I obviously believe that reading poetry to the children in your life is important for many reasons and I hope you do it. If you’re already reading poetry in your home, keep going! Go, go, go! If you’re not, I hope you’ve found something here that has inspired you to try — just try. You don’t have to love it, you don’t have to start every morning with it like we do, figure out a way to make it yours and just try.

I want to be clear, though — always — that poetry or no, the most important thing remains that you are reading to your kids. If it’s paging through graphic novels together, great! If it’s listening to an audiobook while you drive, great! If it’s playing Wordle together, great! (I mean it!) Don’t overlook the things you are doing, all the gifts of language and literature you’re already giving your kiddos. Every bit of it counts, every bit of it matters.

I believe in you.

Sarah

Submit your ideas!

Once a month I take a deep dive into your questions, wonders, problems. What support do you need, what would you like to hear more about? Let me know! Hit reply on this email, leave a comment, or fill out this form to remain anonymous.

I liked poetry many moons ago, but was put off it in secondary school. Badly taught, and it was a boys' school so poetry was regarded as being for girls. I then rediscovered my love of it at college -- specifically Chaucer and Elizabethan verse romances. A few months ago I signed up for a course and the tutor was brilliant: made every word come alive. I even ended up enjoying Wordsworth. I think the quality of teaching makes such a difference. I think your article is brilliant, and so potentially helpful.

Absolutely love this post Sarah! I've been looking for some poetry collections for my children and really appreciate your recommendations! Thank you!