Good morning!

A big hello and welcome to all my new subscribers 👋 I’m being featured this week on Substack Discover (which just means Can we read? shows up on the front page of Substack, but that’s pretty dang helpful) and it has brought many new eyeballs to my little corner — I’m so glad you’re here.

If you’re wondering who I am — and what you’ll receive from me when — hop on over here for more information.

(Thank you to the Substack team, as well as those of you who have been here for a long time — some for nearly three years! I appreciate every single one of you.)

An important programming note 📝

This newsletter is going on a break for the month of March. (It’s one of my hard-earned secrets of adulthood, a lá Gretchen Rubin: to keep going, sometimes I need to allow myself to stop.)

Because I am still a work in progress as a person and cannot (yet!) step away completely even from this thing that isn’t my real job, even when I really need to, you’ll still receive a few things from me over the next few weeks:

A surprise — a new feature of this newsletter! — that I’m super excited to share with you

Your monthly (How) Can we read? issue, where I take everything I know about raising readers and building a culture of books and literacy in your home and share it with you, bit by bit

My regular weekly schedule will resume on April 4th. Thank you for your ongoing (or brand-new!) support 💗

Today!

Until then, please enjoy this guest post from my wonderful Substack friend, Tania Rabesandratana, who writes the excellent newsletter

:Tania is a science and policy journalist who speaks five-ish languages, grew up in a mixed family, has lived in six countries, and is raising multicultural, plurilingual kids with her beloved. Home Mixed Home is an online nook that celebrates and (tries to) untangle the joyful mess of living in a multicultural family — exploring questions big and small that come up in mixed relationships and parenting and gathering other thoughtful people to figure it out together.

I am incredibly happy to share Tania’s post with you today, as some of you have been asking me about multilingual reading for years, and I’ve never been able to provide much in the way of suggestions or advice.

You’re in good hands.

Multilingual family reading

This post is for you if you want to juggle reading in multiple languages at home with ease and intention. I speak from my experience as a mum in a family that speaks three (sometimes four) languages at home. And because I’m winging it a lot of the time, I have also asked actual pros for insights and practical tips that you can tailor to your tastes and situation.

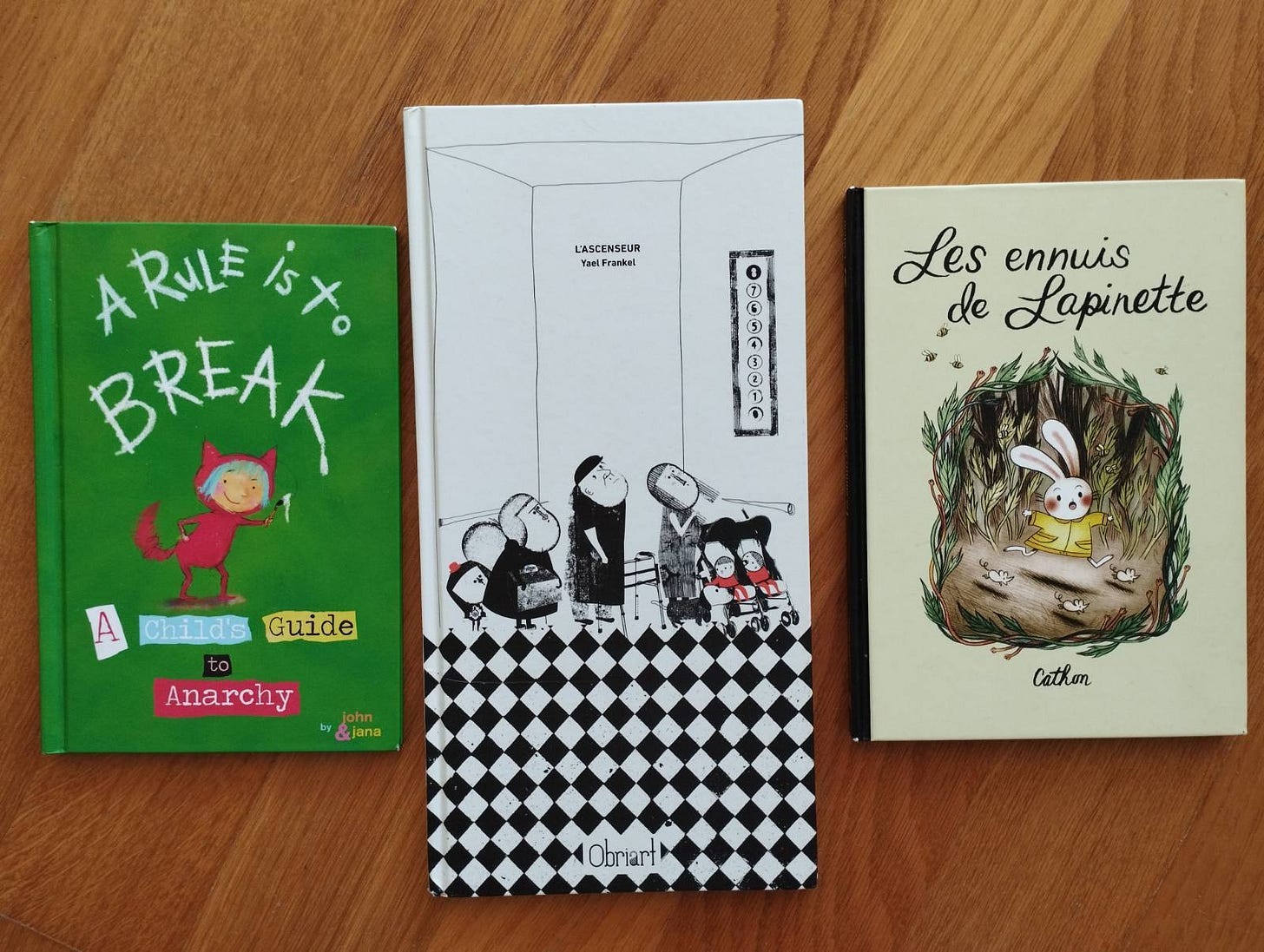

A few books I enjoy reading with my kids, from left to right:

A Rule is to Break: A Child’s Guide to Anarchy by John Seven and Jana Christy (US, in English)

L’Ascenseur by Yael Frankel (Argentina, translated from Spanish into French)

Les Ennuis de Lapinette by Cathon (Québec, French)

Let’s start with your family language setup

What’s the dominant language and the minority one in your family? You might be acutely aware of this if you’re the only speaker of your language in your kids’ life, and have been thrown into a role as de facto guardian of a minority language/culture at home. It takes awareness and effort to maintain multiple languages; that’s true on a macro scale (like a country) and also on a micro scale (like a family).

“Even in bilingual communities, family home reading practices may exacerbate uneven development across children’s two languages,” says researcher Ana María González Barrero in a 2021 study of 66 French–English bilingual families with 5-year-old children in Québec. González Barrero, now an assistant professor in the school of communication sciences and disorders at Dalhousie University in Canada, found that families who are less proficient in one of their two languages tend to have more books, more reading sessions and longer reading sessions in their dominant language. She writes:

Parents need to be aware of the tendency of bilingual families to support the dominant language, as they may wish to consciously allocate more time for reading to children in their non-dominant language and provide access to more books in the family’s non-dominant language.

Of course, we’re busy people with finite resources and energy, and we do not want family reading to be a chore. To make this as easy as possible, I’ve asked my friend Élodie Misrahi for advice. She’s thought deeply about how to handle books and other resources in plurilingual environments—both in her work as a teacher-librarian and trainer in international settings and when raising her bilingual children.

Let’s get practical

What books to get

Obviously, I hope you get books that you and your kids truly enjoy, no matter their language ❤️ Let’s look at specific considerations for multilingual families:

Should we ban translations? I confess I’m an original version snob. For children’s books like for any book, if we can access and read the original, brilliant! But forgoing all translations would mean we’d lose out on so many wonderful stories. For instance, I don’t speak Japanese and am grateful for translations of books by the likes of Akiko Hayashi, Kiyoshi Soya and Tomoko Ohmura:

We also happen to own the same few books in two different languages, and it's fun to compare and contrast them.

Let’s not forget books without text! They’re especially great to gather around and discuss across ages and languages.

Some (almost) text-free books that are well-liked in our home include Pippa Goodhart’s You Choose and the Polo series by French illustrator Régis Faller. (These are fantastical stories that you and the kids can narrate yourselves.)

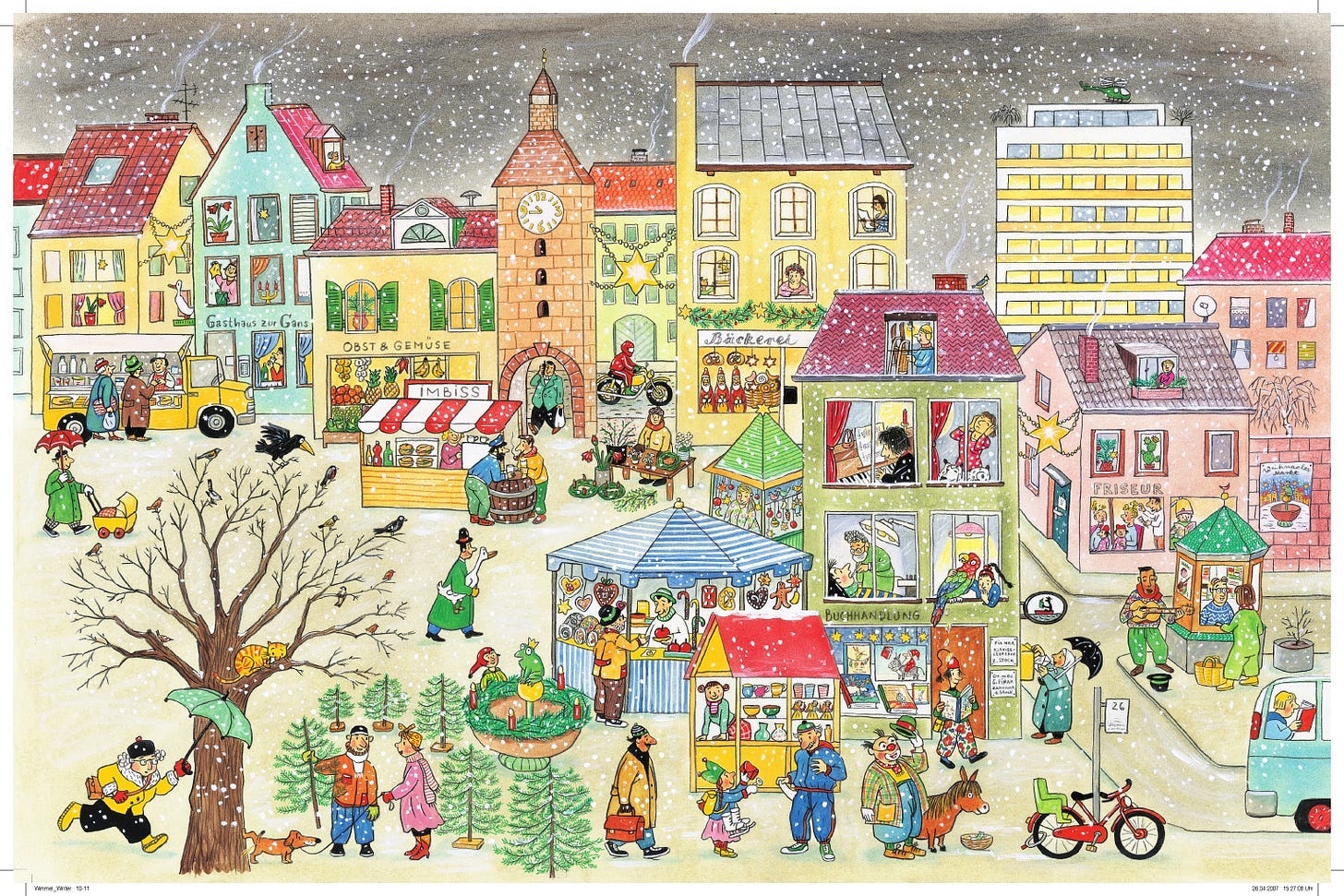

We have also spent hours marvelling at all the details in these library finds: the four seasons books by German illustrator Rotraut Susanne Berner…

… and La Ciutat (the city) and El Camp (the country) by Catalan illustrator Roser Capdevila:

To help build up our kids’ lexicon, shall we favour illustrated vocabulary books [we call them imagiers in French; I don’t know an accurate English word for them] rather than stories? Some are lovely (I like this one we received as a gift!), but let’s be frank, some imagiers feel like tedious flashcards for toddlers. Élodie says she favours “books that give access to [a language’s] culture, stories that stimulate imagination, or rich nonfiction books.”

How to get the books

(Besides the obvious giant online retailers, that is.)

Ask friends and relatives for books in your shared language as hand-me-downs or gifts. If you’re a visiting friend or relative, bring all the books!

Raid your local libraries, for real. (Élodie’s local library in France has a dozen books in Spanish: “That’s not much, and at the same time, if you borrow one per week and rotate them, it’s actually not bad,” she says.) Visit other libraries. Ask your librarians! Explore the depths of the online catalogue. My region’s public libraries are all connected, and I can request books from any of them to be sent to my local branch. Maybe yours have a similar system?

Buy second-hand. Flea markets and garage sales can be frustrating when you look for books in a specific foreign language. I’ve bought used books from online marketplaces like Vinted, which I do realise generates unwanted waste and carbon emissions to ship books across Europe (and is also very convenient when searching for a particular book 😅)

Search for book (or magazine) subscriptions in your language. As a toddler, my eldest received one of the best gifts ever: a book subscription from L’École des Loisirs, i.e. eight carefully selected books throughout the year. It’s just one of many such subscription offerings out there — maybe there’s one in your language, too?

How to store the books you do get

As with toys and foods, book rotation is your BFF. From a high shelf to a low one, from a bedroom to the toilet: rotating books works! It helps you to make the most of your library whatever its size, to keep family reading fresh and entertaining… and to nudge children towards books in a language that you feel needs attention.

One day, I decidedly sorted the kids’ books by language: that system lasted maybe 36 hours. It made zero sense to my eldest, who was four at the time. As Élodie points out, little kids don’t go around looking for a book in a particular language (neither do I, to be fair!): they go browsing for an Astérix album or searching for that Horses and Poneys book. It makes more sense to group books by theme, where they’ll actually look for them, and also stumble upon interesting, related books in the vicinity.

As for the very practical stuff: by size, by colour, in a basket, on a shelf… Choose whatever system works for your family so that your kids do access the books. I also like the sticker system at my son’s multilingual school library: one colour per language, except for books in the school’s dominant language, which bear no sticker.

Let’s read!

Both the quantity and quality of your reading sessions matter to support literacy development in children, González Barrero told me in an email. And if you or your child don’t feel like reading, she suggests looking for “a different way to provide high-quality language interactions such as playing, storytelling, etc.” (Also I reckon it’s okay to say: “I’m really tired right now, shall we cuddle and talk about your day?” or “That book’s in Russian/Arabic/etc., ask grandpa!”🤭)

To switch or not to switch

You’ve probably heard about the “one person, one language” (OPOL) principle, whereby each adult should stick to their native language for consistency. If you’re part of a multilingual family, you also know how it is in practice: y’all end up mixing things up (go read my interview with Max Antony-Newman to set your mind at ease about this!), at least some of the time. Linguists call this codeswitching: alternating between languages in a single conversation (or reading session). “Codeswitching is a natural behaviour in bilinguals, and parents should read books to their children in the language they feel more comfortable with,” says González Barrero.

González Barrero points to these two studies showing that different types of translation or codeswitching strategies can support learning in shared book reading:

A study by Melanie Brouillard et al (2022) showed that children learned new words from monolingual or bilingual books, so book type didn’t affect vocabulary learning.

A study by Kirsten Read et al. (2020) showed that books that included some code-switching supported word learning in 5-year-olds.

Sometimes, I’ll read aloud in my native language when the book is written in another, like a UN interpreter of El Monstre de Colors. This is neither a practice I recommend nor a habit to ban, it’s something I found myself doing—and that González Barrero also observed in her study. As Élodie points out, this will also depend on your own situation: your language/translation skills (and theatrical) abilities, your tastes, the style of the book at hand, your energy levels, etc.

By the way, being flexible and pragmatic about OPOL applies to all caregivers! I remember my eldest at 3-years-old, begging my mum to read a book in Catalan—which she patiently did, although she doesn’t speak the language. I found this both endearing and irritating (“That’s silly, she should be reading in French”). But it can be a cute way to bond, reading Yakari and giggling about granny’s accent together.

I hope you’ve found some ideas and encouragement here. Try things out, take what works for you and your family today, and leave the rest! I hope you have tons of fun sharing books with the children you love ☀️

A huge thank you to Tania for this terrific advice today. If you have questions for her, or would like to share your own experience with multilingual family reading, please leave a comment👇

I’ll see you on the flip side of March. In the meantime, keep reading to the children in your lives — you’re doing a great job!

Sarah

Congrats on being featured and thank you for the intro to Tania's writing. We are a bi-lingual home and so much of what she shared resonated!

Sarah! How fun that you're featured! I'm glad you're taking a break in March (I'm glad for you, not for me) AND I'm also excited to hear about the surprise:).