How caregivers can support young readers at home

Can we read? No. 79: A guest post from Randee Bergen

Good morning! ☀️ I’ve got an absolutely awesome guest post for you today.

A huge thank you to Randee Bergen, who will tell you more below, for collaborating with me to bring you this super practical and useful information about how caregivers can support young readers at home.

Let’s get right to it!

Hello to the fans and supporters of Sarah Miller! What a pleasure it is to find Can We Read? in our inboxes and take a few quiet moments to just think about and appreciate children’s books.

My name is Randee Bergen and I am the author of Busy Bee Kindergarten.

My Substack newsletter is primarily for teachers — it is chock-full of video footage of teaching and learning in action in my kindergarten classroom as well as information about the science of learning to read — but parents and other caregivers subscribe as well, especially those who are teaching their young children at home and trying to ensure the best start possible to a wonderful literate life.

Today, I am happily doing a guest post for Sarah, as she did for me last month. Sarah asked if I would write about ways parents can support their young readers at home. While you can find endless generic ideas with a simple Google search, today I present my own list of the slightly less conventional.

Don’t Read to Your Child

Say what? Don’t read to your child?! Yes, that’s what I said and, yes, you can and should read to your child; but there is a lot more to it. I’ll tell you a little story about what made me say don’t read to your child for the first time and why it’s important to say it to you now.

Twenty-some years ago when my daughters were toddlers, I had a mom friend who had a daughter of about the same age. She was over at our house once and her two-year-old kept asking to have the same book read to her. The mom would open the book, read every page as fast as she could, close it, and roll her eyes as if it was such a boring and worthless activity. Her child immediately opened the book up again and stood there expectantly. I watched — entertained, perplexed, and, ultimately, horrified.

I was fairly new to parenting myself, but I was a seasoned teacher and had plenty of experience reading to young children. I could see what was happening here. The two-year-old was controlling her mother (no judgment, as I’m sure most of us moms have been controlled by our young children more often than we care to admit). The youngster never looked at the pages; most of her pleasure and desire to continue this activity was based on her budding understanding of cause and effect. I give the book to my mom and she babbles like an idiot. I give the book to my mom and she babbles like an idiot. Does it happen every time? I’m not sure; I will give her this book over and over again to test it. That was the entertaining part.

But I was perplexed, too. Why wasn’t this mom interacting with her child? Looking more closely at the book, I realized she should have been pointing to the illustrations, talking about what she saw, asking her child questions, building vocabulary, helping her child make connections with other books or things in her life, and encouraging wonderment and awe. In other words, she should have been doing so much more than just reading to her child.

And then the horror and this thought hit me. Oh my, is this what parents think it means when they hear that they should read to their child? Do they — like this well-educated mature mother — think that they’re supposed to just open the book and read the words from cover to cover and that is all?

And that is why I sometimes say don’t read to your child. Rather, open a picture book and talk to them about it. And let them talk. Use the illustrations to build up their language skills and their knowledge base because, ultimately, these two things will have the greatest effect on their future reading comprehension.

Of course, you will eventually want to get around to reading the book, some other week or month or year. Or, better yet, you can read and stop on every page to talk about things. Books are amazing and should, of course, eventually be read as the author wrote them.

Before moving on, I must say that you need to be cautious about books that are read to children online. The same thing is happening — someone is reading without doing any talking. They’re not explaining new words; they can’t possibly help your child make connections since they don’t know your child’s life; and, too often the pace is much too fast for youngsters to comprehend, thereby training them to just tune out. Not good.

Introduce Compound Interest

As in math and savings accounts and all that? Once again, no, not really. Here, I am talking about compound words. One of the big skills that preschoolers and kindergartners need to learn is how to hear the smaller and most distinct parts of our language. In kindergarten, we work a lot on phonemic awareness; that is, we listen for, isolate, and manipulate (delete and substitute) the smallest sounds in words. These small sounds are called phonemes. Examples are /m/, /sh/, and /ou/.

But you can’t jump right into phonemic awareness training at home. You have to start with listening to larger chunks of language, such as words and syllables. This is called phonological awareness. To get started, I suggest you introduce interest in compound words.

When eating hotdogs, say, “Hmmm… hot, dog. I wonder why they call these hot dogs. They’re hot, but they’re not dogs.”

If your child has a sleeping bag, “Sleeping. Bag. Yep, that makes sense. It’s a bag and you sleep in it.”

When it rains, “Rain. Storm. Oh I see, it’s called that because it’s raining. If it was snowing, it’d be a snowstorm. If we hear thunder, we can call it a thunderstorm. Did you know that in some places sand can start blowing all around and they call it a sandstorm?”

Really emphasize the two parts of the compound word. This is the beginning of phonological awareness, which will eventually encompass phonemic awareness. It’s also the beginning of really listening to and learning to love language.

Stutter

Really? But why? When I say stutter, I mean bounce the first sound of words (t-t-table) or elongate the first sound (ssssssssandwich). You and your child can have fun with this. “Did anyone feed the c-c-cat?” “Hey Mmmmmmmom, how are you doing?”

Speaking like this draws attention to the first sound — the first phoneme — in words. Your child will eventually need to be able to hear the first sound in words to start learning how to spell. For the first several weeks of kindergarten, we do this activity but in a more structured way. It’s never too early to do this with kids, though. A favorite story of mine involving my now 25-year-old daughter is when she was two and her grandma gave her the (VHS) movie Tarzan. I, of course, would sometimes refer to it as T-T-Tarzan. My daughter, being sassy, would say, “No! It’s C-C-Carzan.” She had heard so many beginning sounds that she was already substituting them (a mid- to late-kindergarten skill). And, boy, was she having fun with it. We have it on video. Such a cute memory.

Use Inappropriate Words

Oh no, now what? Don’t worry, I’m only talking about using developmentally inappropriate words. Never, ever assume that your young child can’t handle big words. Small children love sophisticated words and expressions; in fact, they’ll often pay more attention and remember them more easily than regular, age-level vocabulary. A recent teaching article I read about vocabulary development gave the example of a teacher saying, “Please dispose of that rubbish” rather than “Please throw that away.” This is another example of having fun with language.

I teach the Habits of Mind in my kindergarten classroom and my five-year-olds can articulate and correctly use terms such as managing impulsivity, persisting, striving for accuracy, and communicating with clarity. As soon as I introduce these words and we talk about what they mean, I hear students using them. And parents will say things to me, like, “This weekend my son accidentally popped a balloon and he apologized and told me he was being impulsive.”

Three considerations for using words that may have formerly seemed inappropriate:

Let words arise organically. Throw them into your daily conversations, point them out in books, but do not make a list of words to learn.

Define new words using child-friendly language rather than the true definition. A good example is saying that a liquid is “something that sloshes around” while swirling your favorite beverage.

After talking about a new word, be sure to use it often and find opportunities for your child to use it so that the word and its meaning will stick.

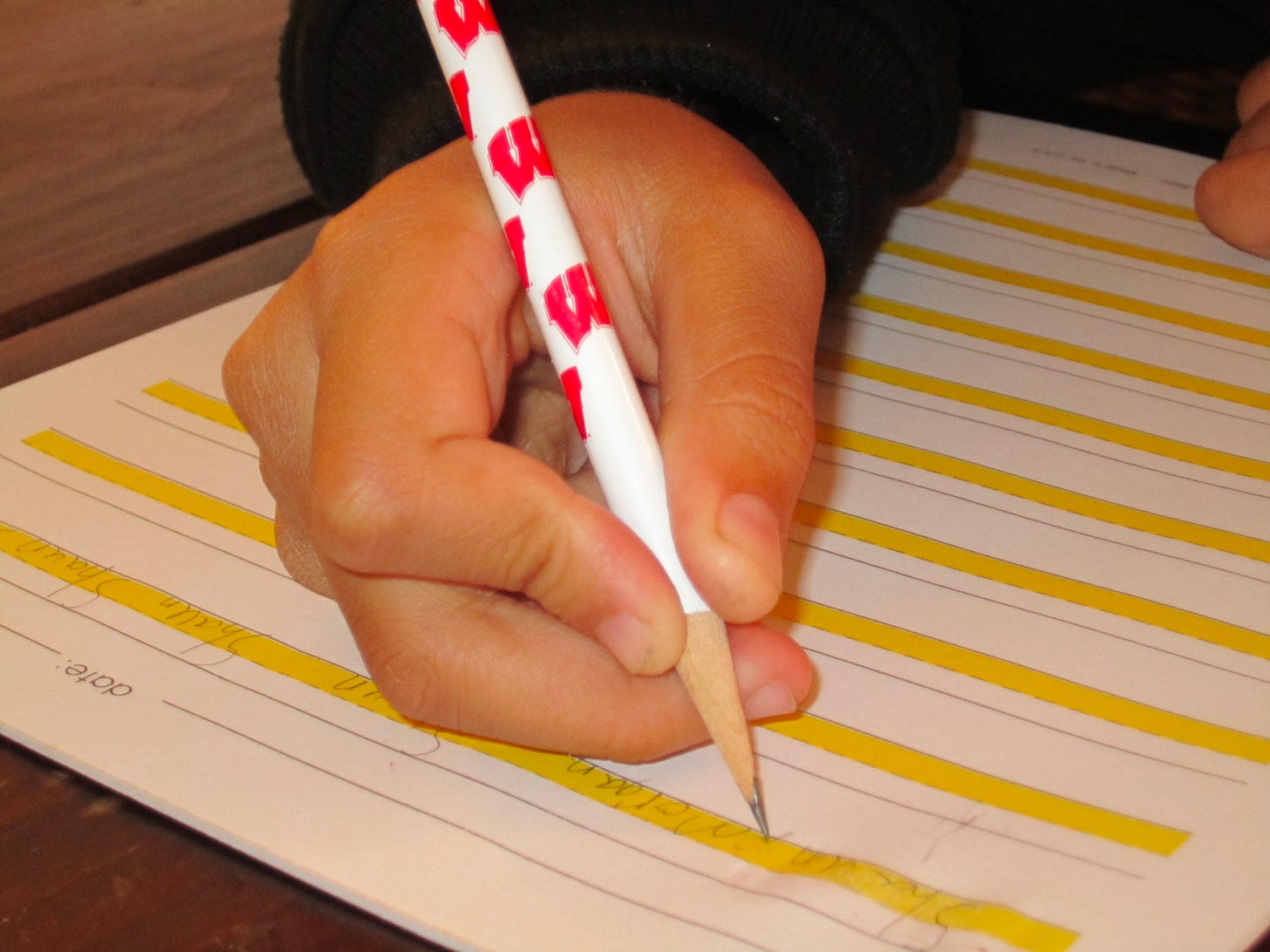

Encourage Pinching

Now we’re getting physical? And it involves hurting others? No, there’s no pain involved. This has to do with grasping writing utensils. Whether you’re giving your child crayons, markers, or a pencil, model the correct grasp — a tripod/three-finger grasp, shown below — and encourage them to always use it.

A fun way to teach this is to lay the writing tool on the table in front of your child with the tip-end closest to the child. Start slowly by saying, “Pinch it!” and have your child pick up the tool and grasp it correctly using three fingers. Model as needed with your own writing tool and move their fingers around if need be. Remind your child to “pinch it” if their fingers are not quite in the right place or if the grasp is weak. Repeat this a few times. When your child can mostly get the grasp without you manipulating their hand, then the fun begins. Now, when the pencil goes down for the next try, you can sit quietly, look around the room, check your fingernails, and, when your child is least expecting it, yell, “Pinch it!” The goal is to startle your child and make them laugh and have them pick up that pencil as quickly as they can.

You might need to analyze your own pencil grasp and be ready to temporarily change it in order to model the most preferred grasp. If children come to school with an already established “wrong” grasp, it can be difficult to change it. The correct pencil grasp facilitates neater handwriting and lessens fatigue. So please keep an eye on how your child is holding those utensils and always encourage the pinch!

Get Bossy

More fun. Many children begin to write letters at home by copying letters they see in print or letters that have been written by parents specifically to be copied. It is important, from the beginning, to model correct letter formation and expect your child to try to write letters correctly. I have tried-and-true letter formation cues that you can use for this purpose. A letter formation cue — such as down, trace it up with a bump, bump to make a lowercase m — is meant to be spoken by the child to their writing tool. They are talking to the pencil and telling it what to do. They say the word down just as they make their pencil go down on the paper; then they say trace it up and their pencil goes back up the same line; when they say bump, bump, the pencil will do as they say and make the two bumps. It’s fun because they get to boss the pencil around.

You will need to keep the letter formation cues handy. You’ll need to model how to make each letter (yes, you’ll become aware of how “wrong” you write). And you’ll probably need to do hand-over-hand with your child to show what it means to make a pencil do exactly what your mouth is saying.

Handwriting is another thing that is challenging to change when a student arrives at school. If you’re going to let your child write letters — and I recommend you do — stay in the general area and encourage the proper letter formation. Start by teaching how to write the letters in their first name, the first letter being a capital and all the others lowercase.

And play up how fun it is to boss around your pencil!

I hope these ideas are helpful and that the silliness will help them stick with you. Just remember not to read to your kids, compound interest, stutter, use inappropriate words, pinch, and get bossy! There is so much fun to be had with children this age; I have a feeling you already know that.

Please let me know if you have any questions. [Ed: leave a comment below, or email Randee at busybeekindergarten@substack.com.]

Sincerely,

Randee Bergen

Two of my favorites collaborating! 🐝 📚