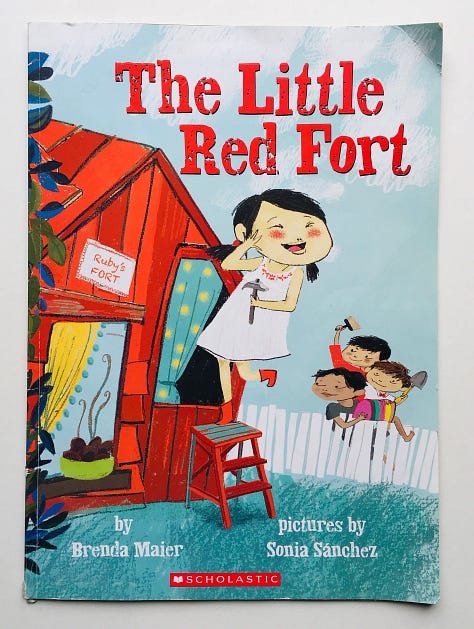

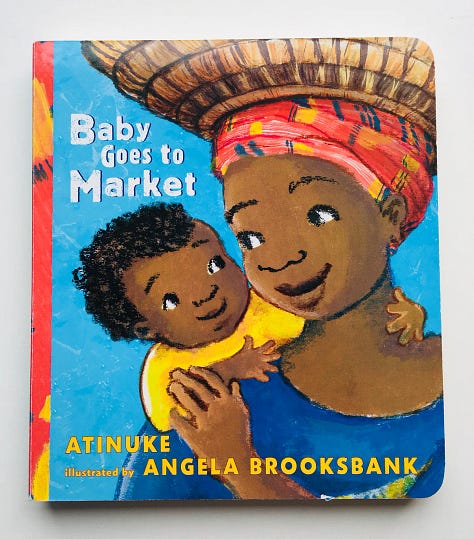

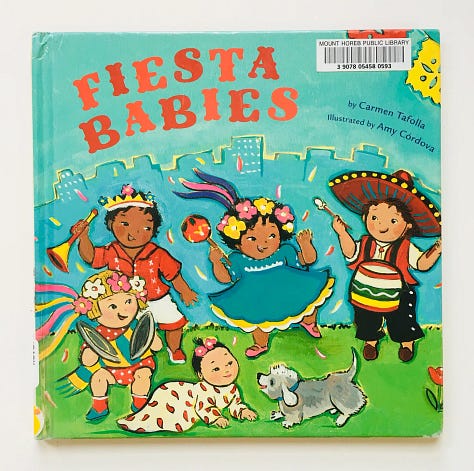

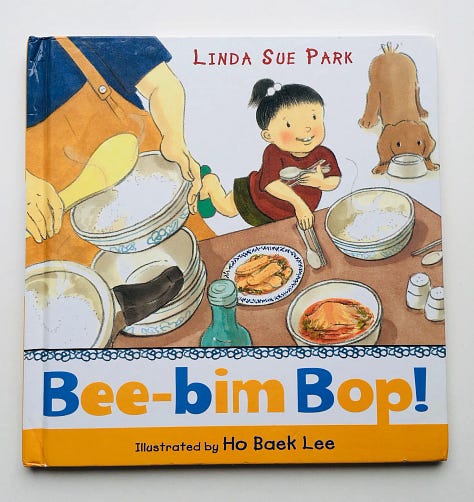

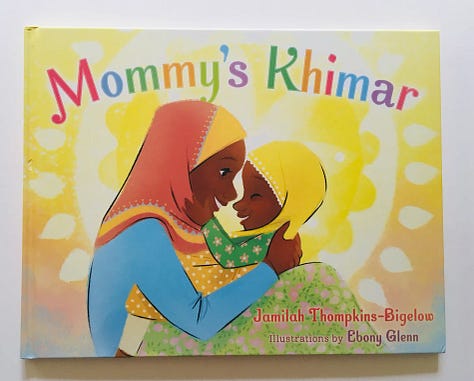

I originally published this post on August 13, 2021. I have edited and updated it since then, though the heart of it remains the same. All of the photos included are of inclusive books I’ve reviewed in the past and highly recommend.

Once upon a time, a subscriber asked me:

What’s your philosophy on diverse reads and how does this inform how you approach books featuring other races/ethnicities/cultures with your kids?

That excellent question was the genesis of this issue. Though I originally wrote this two years ago, my philosophy on diverse reads has been central to Can we read? since the very beginning. If the core of this newsletter is about helping people find great books to read to children, the next layer is about diversifying what is being read.

Today I offer you what I’ve put into words. I want to be clear that I am not a subject matter expert on representation in children’s literature or inclusive books — I do know a lot, and I’m about as passionate as it’s possible to be, but I share my knowledge on this topic with humility. I also share from a place of deep conviction and hope that things can be different, that every child can see themselves in the pages of a book and that in acknowledging and honoring our differences, we can build a better world than this one.

Two notes before we begin:

📝 I have said this before, but it bears repeating: using the word “diverse” to mean “non-white” centers whiteness, so I strive to use the word “inclusive” instead (except when using more specific inclusive language would be a better descriptor of a book, character, author, illustrator, etc). Because the word “diverse” is the one most predominantly used re: the topic of inclusive, representative, and anti-bias children’s books, you will encounter it here, meaning a range of books about all kinds of different people with every sort of identity.

📝 Which is a good segue: I want to emphasize that race and ethnicity are only two areas of diversity. What I’ve written here focuses heavily on those characteristics because I begin with data that reflect them, but obviously, inclusivity also encompasses culture, religion, age, sex and gender, sexual orientation, disability, neurological conditions, socioeconomic background and class, and more. When assessing your choices, bookshelves, or anything else related to representation, keep your lens wide. Your education — and your home library — will be richer because of it.

Every year, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, part of the School of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, compiles data on books by and about Black, Indigenous and People of Color published for children and teens. Every year, I read the data and feel a heady mixture of discouragement, overwhelm, and anger. Why is publishing inclusive books so hard? Why can’t more children see themselves — and others unlike themselves — in more books? Shouldn’t this issue be improving?

The CCBC Diversity Statistics are unparalleled and if you’d like a look at them over time, you can see that here. These are the results from the past five years:

The CCBC librarians and staff have been around since 1965, and gathering this information since 1985, so they are uniquely positioned to share trends over time as well as reflect on what has changed. Indeed, in February 2021, four CCBC librarians offered their Observations on Publishing in 2020. It was the first time I read something about the data that didn’t make me feel like pounding my head against a wall:

[The ellipses represent places where I have removed all the examples of titles that meet these criteria, for easier reading]

“The most welcome thing we noticed in 2020 was the number of outstanding books that speak to the many-faceted lives and experiences of Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC), from those that are directly and intentionally affirming…to those that affirm through the simple yet profound importance of authentic visibility. We were also thrilled to see so many terrific first books by BIPOC authors, with these debuts crossing genres from contemporary realism to memoir to fantasy... We also noted the growing number of books that expressly acknowledge awareness of race and the impact of racism on the lives of children and teens, whether it’s a major theme or revealing moment of the story… and including books addressing what is happening to Latinx immigrant children at our country’s southern border... And in a year in which children and teens were witness to, and sometimes participants in, protests and marches, we were glad to see picture books expressly about activism and resistance…

This is incredibly good news, and while a small part of me knee-jerks to asking, why did it take so long?, a larger part of me is simply glad that it is happening.

This is all to say: diversity in children’s literature has long been a very serious problem (it’s getting better but it’s still a problem), and it’s important for many different reasons. If the issue of diversity in children’s literature — and why representation matters — is new to you, I encourage you to dig into, learn from, and reflect on any of the following resources created by people much more knowledgeable than I am:

What are Mirrors and Windows? via We Are Teachers

More about mirrors and windows (with different attribution as to who first coined the phrase): Why We All Need to Read Diverse Books to Our Kids via MotherMag

My philosophy

My philosophy on inclusive reads is that kids — ALL kids — need to see themselves reflected in the characters and images of the books they read, and in the creators of those books, too.

My philosophy on inclusive reads is that children take their cues from us. If we avoid books about people different from us, this sends a message about who we are, what we think, and what we believe about other people.

My philosophy on inclusive reads is this:

“Literacy is a social act, and I find that my reading of the world is better when done in collaboration with others who do not share my view of the world, my history, or my identity.”

(I borrowed those words because they perfectly capture my feelings — credit goes to Dr. Laura M. Jimenez, a lecturer at Boston University Wheelock College of Education and Human Development, and this post on her blog, Booktoss.)

My philosophy on inclusive reads is that the types of books I choose to bring into our home hold power. It is up to me to use those books wisely, for the betterment of my children, my family, our community, and the world.

Approaching books

The most interesting part of the initial comment that prompted this newsletter issue is the question of how my philosophy informs how I approach books. I thought about this for a long time.

My philosophy informs my approach in a step-by-step kind of way, which assumes:

There is a problem with my home library if there are not enough representative and inclusive books.

It is up to me to solve that problem. It is my responsibility to my children, and to other people’s children.

I will do something about it.

Below are the ways that I have done (and continue to do) something about it.

🔎 Research, and listen

First, education. If you want to make a change or do better, you have to know where you’re starting from and how to move forward.

Social Justice Books has two outstanding, clear resources that taught me how to cull and improve our own home library, as well as the critical criteria by which to assess any/all books we come in contact with. (I strongly encourage you to check both of these out.)

First, Creating an Anti-Bias Library. The guidelines in this post are very helpful:

“An anti-bias library maintains a balance of books that portray:

A variety of ways of life. A range of families are depicted: urban, suburban, rural, with or without financial resources, and with women and men in a wide range of roles

A wide range of family structures in stories that engage young children

Blue-collar workers, farmers, service workers, and artists as well as professionals and white-collar workers

Differently-abled and able-bodied people actively taking initiative and filling a range of jobs and roles in the family

Diversity of looks, work, family, and way of life within all racial and/or ethnic groups

Able and differently-abled children from all racial/ethnic groups, genders, and classes as active participants in the stories

Real people from all kinds of backgrounds—children and adults—engaged in actions for change, reflecting current lives as well as lives from the past. Past lives should include everyday people, not just famous individuals.”

Second, a Guide for Selecting Anti-Bias Children’s Books by Louise Derman-Sparks. This resource teaches you what to look for, and check, point by point:

Check the illustrations.

Check the storyline and the relationships between people

Look at messages about different lifestyles

Consider the effects on children’s self and social identities

Look for books about children and adults engaging in actions for change

Consider the author or illustrator’s background or perspective

Watch for loaded words

Look at the copyright date

Assess the appeal of the story and illustrations to young children

In that guide, Derman-Sparks also writes this, which I think beautifully states the end goal:

“Some early childhood teachers wonder if it is necessary for every book in their collection to show diversity. Every book needs to be accurate, caring, and respectful. However, you will want individual books about specific kinds of people (e.g., a biracial family or a family with adopted children). Diversity becomes essential in the balance of your book collection, where you want to avoid invisibility or tokenism of any group.”

Let’s repeat that because it’s super important:

➡️ Every book needs to be accurate, caring, and respectful.

➡️ Diversity is essential in the balance of your book collection.

Ultimately, this is how I think about and approach children’s books, including inclusive ones: I ask myself, what will kids most likely walk away from this title believing about XYZ people? I look at who is included and who isn’t. I look at what’s said and what’s not. I look at what shows up in the illustrations and images and what doesn’t. What will children learn from reading this book?

I also listen to many people with personal and/or professional experience addressing bias in children’s books, building inclusive libraries, and — because those things usually go hand-in-hand — often both. These are some of my resources:

Brightly: Raise Kids Who Love to Read newsletter

Lessons from Turtle Island: Native Curriculum in Early Childhood Classrooms by Guy W. Jones and Sally Moomaw

@heritagemomblog and her blog, Heritage Mom

Lee & Low Books blog

A Broken Flute: The Native Experience in Books for Children by Doris Seale and Beverly Slapin

We Need Diverse Books website and @weneeddiversebooks

🔎 Assess the books you have

Onto action.

After I learned what to look for (and what to avoid), I audited our bookshelves. I cannot possibly encourage this enough.

This can be as in-depth a process as you want — I have done it the hard, long way, taking every single title off my shelves and dividing them into different piles (using CCBC’s categories, as well as some I made up myself) and seeing where I’m doing well, where I’m doing okay, and where I need to do better, as well as the short, easy way, which is just walking by my shelves and thinking about what we have. The latter is, obviously, a lot more work, but also a lot more fruitful.

Is this a perfect process? Do I have the best and most inclusive home library possible? No, and no. I learn more every day (and as such, I do regular audits, both in-depth and less time-consuming ones). I know — and will readily admit — that I have not yet achieved the balance I want (though I can also say that since I wrote this two years ago, I’ve made a ton of progress). But this self-knowledge gives me a point of reference from which to work — I know where I’m lacking and where to begin.

My hands-down favorite resource for addressing holes in the diversity of my home library is Social Justice Books booklists. Those lists not only help me drill down into categories I might not even have thought of otherwise, they help me see more clearly what’s missing on my shelves.

(It’s worth mentioning that a bookshelf audit doesn’t have to stop at your children’s shelves: what does your bookshelf look like? What about your children’s media — TV shows, audiobooks, apps, and video games?)

🔎 Make different choices in the future

There are certain times of year I know I will be buying books (I mean, other than constantly and all the time): birthdays, holidays, etc. When I figure out what I want to purchase, I strive to make balanced choices.

For example, let’s say I know I want to buy my almost-7yo a couple of early chapter books — I will look for titles that are mirrors for her (ones that reflect her own experience) and ones that are windows (ones that reflect the experience of others).

In short, I look for a variety of options, and I especially look beyond whatever’s popping up at the top of search engines or on Amazon.

If I know I want another version of Little Red Riding Hood, I don’t just buy another white version of Little Red Riding Hood — I follow a recommendation from one of my trusted voices, or I search for, let’s say, “Latinx Little Red Riding Hood.” (I might end up with Federico and the Wolf by Rebecca J. Gomez, Pretty Salma by Niki Daly, or Little Red Riding Hood by Jerry Pinkney, all wonderful.)

If I am looking for a holiday book — let’s use Valentine’s Day — I google “diverse Valentine’s Day books for kids” or some combination thereof (“diverse” still works better than “representative” or “inclusive” in the land of search, fwiw).

In making my choices, I prioritize books written and/or illustrated by people who are a part of the group they have written about — for example, choosing Native authors when the subject matter or characters are Native. (These books are often called “own voices” titles, but the industry is moving away from that terminology toward more specific language, which I applaud and have chosen to do myself.)

If the idea of doing this kind of legwork overwhelms you:

You’re in the right place. I include at least one inclusive title in every single issue of this newsletter, which has hopefully already helped you begin to diversify your library.

Email me for recommendations if you have a specific need or type of book you’re looking for. This is one of the benefits of being a paid subscriber.

Ask your local librarian! Librarians know books better than anyone else on earth, and whatever they don’t know, they will find for you. Use them!

🔎 Acquiring books

If you want to delve into the truly obsessive details of my book-buying life, I’ve written about it — all the gory details.

When I’m not getting dirty and aggressive over used books in some poorly-ventilated library meeting room or placing online orders through Thriftbooks, I support independent booksellers as often as possible when buying new books. When I am buying books to improve the balance of diversity of my home library, I try to support diverse booksellers that are relatively local to me, primarily:

A Room of One’s Own, a feminist bookstore in Madison, WI

Birchbark Books, a Native-owned bookstore in Minneapolis that has the single-best collection of Native-focused children’s books in the U.S. (If you ever get a chance to visit in person, it is a revelatory experience)

Semicolon Bookstore, a Black-woman-owned bookstore in Chicago

I prioritize buying inclusive books new — as opposed to buying them used or borrowing them from the library — because money talks: this is the only real way to send a message to publishers that we want more of these books.

But, of course, buying books is not the only way to acquire books: you can also help your local library and/or library system by making a purchase request for representative and inclusive titles. Some libraries have a form to fill out on their website, some have a form to fill out in person, some don’t have a formal process and you just have to ask whomever’s behind the desk, but hear me when I say this: you can ask. Libraries have funds for acquisition and while they may not honor every request (nor, probably, should they), your requests do matter.

Recommended resources

In addition to the people, websites, and books I mentioned above, here are other resources I highly recommend as you learn more about inclusive reads and work on/develop your own library:

Stories of Color: Find diverse living books for your children (I wrote about this incredible resource in August 2021, and it has only gotten better since)

Where to find diverse books via We Need Diverse Books

1000 Black Girl Books Resource Guide (a searchable database)

Today’s takeaways, or some things to consider:

How much do you know, right now, about the state of diversity in children’s literature? Do you think it matters? Why or why not?

What is your philosophy on diverse reads?

Do you know how to assess books using anti-bias criteria?

Who, if anyone, do you listen to, and what resources do you rely on to educate yourself on this topic? Do you need to find more of them? Different ones?

Have you ever done an audit of your home or classroom library? Is this something you’re willing to undertake? Why or why not?

Do you make different choices or seek out alternatives when selecting books to bring into your home or classroom? If not, could you commit to doing this in the future?

Where do you normally purchase your books, and does that process align with your values? (Your values don’t have to be the same as mine! but reflecting on why we do what we do is worthwhile.)

Have you ever made a purchase request at your library? Do you know how to do it? What do you think about the availability of diverse, representative, and inclusive books at your local library or in your library system?

What is one thing you will take away or do differently from now on after reading this issue? (If it helps you to have an accountability partner, hit reply and let me know what you’re thinking or planning on doing. I love hearing from you.)

You may not feel as passionate about this topic as I do, and that’s okay. (I think it’s worth getting fired up over, but I spend more time in the world of children’s literature than your average bear.) I work daily, literally daily, to shape and balance my home library toward greater and greater diversity. In this newsletter, I committed from the very beginning to covering at least one inclusive title per issue and I have done that — I will continue to do that come hell or high water. These are things I can do, these are ways I can support my children and yours.

The books you share with the children in your life — the titles you read aloud, the ones you bring into your home or classroom — hold weight, hold power. What’s in them (and what’s not) is important. It matters.

I hope this issue has been helpful to you. If there is someone you know who might benefit from it, please pass it on 📤

May we all make good and ever better choices for the benefit of all children — mine, yours, ours.

Sarah

Great article, Sarah!

I would add one more resource for folks who are interested: http://www.westories.org

WeStories was an organization founded in St Louis after Mike Brown’s murder, focused on using children’s literature to help white families talk about race and racism. They recently closed the organization, but have made their (really excellent) curriculum available at the website above.

I recently became a subscriber and have been going through past issues, and putting some of the books in your lists on our hold lists. It’s been loads of fun. Last week we checked out Bathe the Cat. The kids have been laughing a lot when we read it.

Today our childcare provider (who is a loving, engaged POC and makes my life so much easier) let me know she thought Bathe the Cat was too much for a 5 and a 3 year old. Two dads? Why introduce that? Why so many books about being brown? Why do I keep checking out books about differences? It made me profoundly mad and sad to even have to explain representation. It’s been a few hours and I’m still upset about it. Sigh. 😔 Thanks for reading