Can we read? No. 8

Reading to my children as a way of hanging on right now

“So as a mother and as a writer, let me urge you to read to them, read to them, read to them. For if we are careless in the matter of nourishing the imagination, the world will pay for it. The world already has.” (Katherine Paterson, A Sense of Wonder, 1995)

Truth be told I’ve been asking myself lately whether this matters: why, really, is reading to my children important at all right now? What difference does it make? (That voice in my head that whispers in an evil tone: none, none, NONE.)

I don’t really believe that. And I’m thankful that I am still, somewhat, okay enough to recognize when I have left the realm of right-sized thinking and gone off into the big dumb echo chamber, that expanse of murk where I feel lost and totally unmoored, where all the fear lives (and wow, does that fear take up a lot of room these days).

That Katherine Paterson quote is why it matters, that we read to our kids, that we take the time every single day to press our bodies to each other and leave for a bit this earthly place through words and images and the brilliant, unfailing power of our own minds. It makes a difference that we are still here, doing this thing that has remained, blessedly, unchanged (except in the best ways in my house, of picking more advanced stories, and of supporting the slow, steady growth of a new reader). I’m not going to hold up reading on the same level of, say, brushing teeth: but then again, why not? Both keep us healthy. Both remove the bits of gunk that have stuck to us whether we like it or not. Both leave us cleaner, brighter, closer to our realest selves than we were before. Isn’t that rather important? Doesn’t that matter a whole lot?

Let us not be careless in nourishing the imaginations we are so lucky to have in our charge: those of our children and our own. Stories have helped us survive from the moment we sat around in caves and muttered some guttural sounds in one another’s direction. It’s the way we endure, the way we keep our people and places and pieces alive inside of us, so we don’t forget that we aren’t alone, so we don’t live through anything with the mistaken belief that we are the first to do so. (I have been telling myself constantly lately: if my great-great-great-great-great grandmother could, as a single mother, lead her 14 children across the Great Plains from Illinois to Utah, I can damn well handle quarantine, health issues, homeschooling, and basically anything else.)

Let’s keep telling stories, sharing stories, using stories to keep us strong.

It matters.

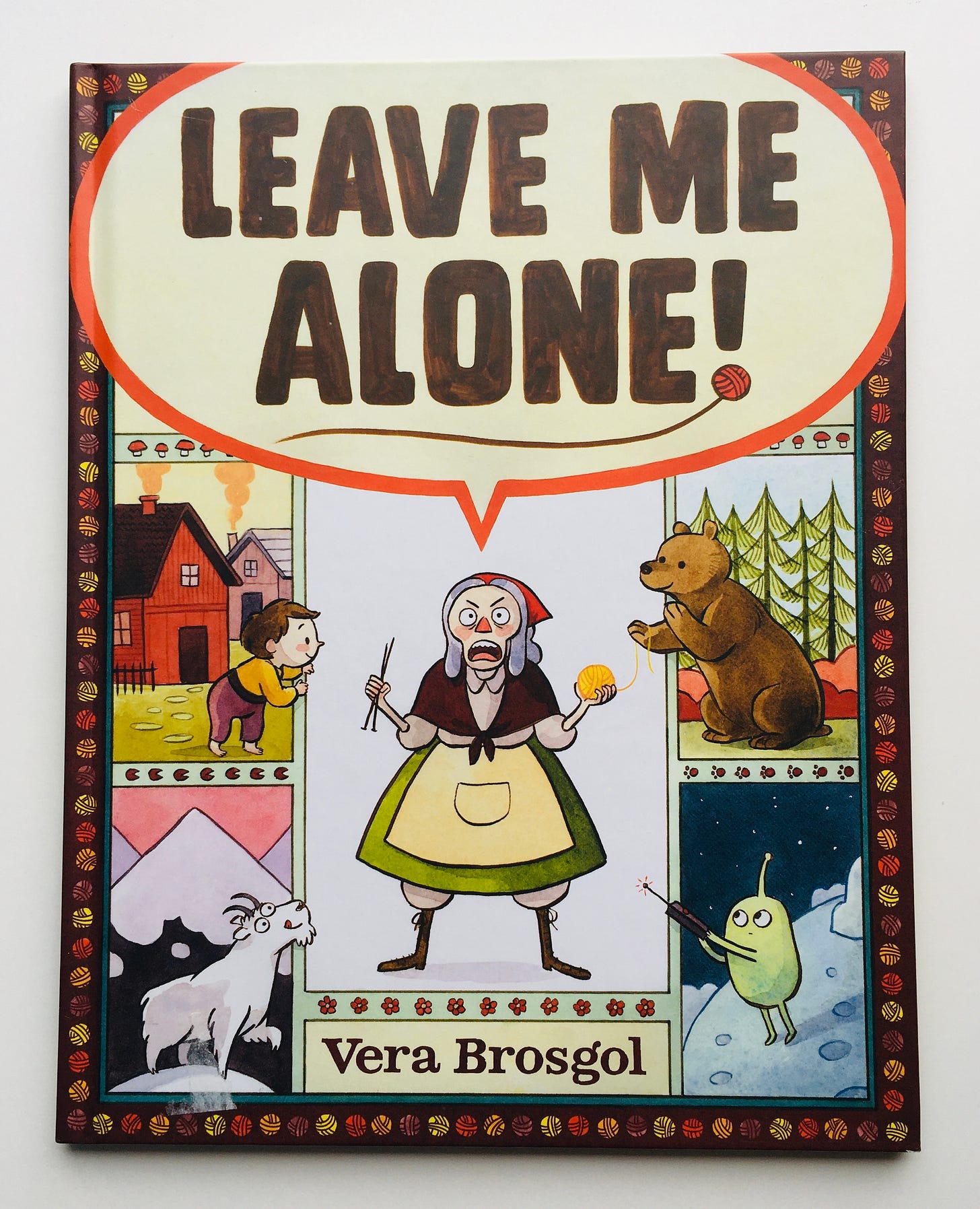

Leave Me Alone! by Vera Brosgal (2016)

My brother took one look at the cover of this book a few weekends ago and said, “Oh, someone made a book about you!” YES, YOU’RE SO FUNNY. (Except he’s right.) So it’s no wonder, really, that I love this book. I can deeply relate to the starring grandmother here, cooped up in a small house with way too many children. She has a lot of work to do — winter is coming and she has an untold number of sweaters to knit, but the knitting just isn’t getting done. “Her grandchildren were very curious about her knitting: were you supposed to hit the ball with a stick? Could you eat it? Could you make your brother eat it? Why did the ball get smaller and smaller as you chased it?” The grandmother has had it (I think understandably) so she tidies up, makes sure the children are taken care of, and hits the road, yelling “LEAVE ME ALONE!” as she goes. She tries to live with some bears, then some goats, then she climbs to the moon, all to no avail, until she finds a rip in the universe. In the peace and quiet there, she finally finishes her 30 little sweaters and gets some much-needed alone time before realizing: without 30 little grandchildren to put into sweaters, she’s alone. Sometimes it’s hard for children to understand why grown-ups might need a little time to themselves to recharge and renew their sanity — this titles does an elegant job of explaining that through uproarious humor and subtle grace — while also making clear that leaving and being alone is followed by good-natured coming home.

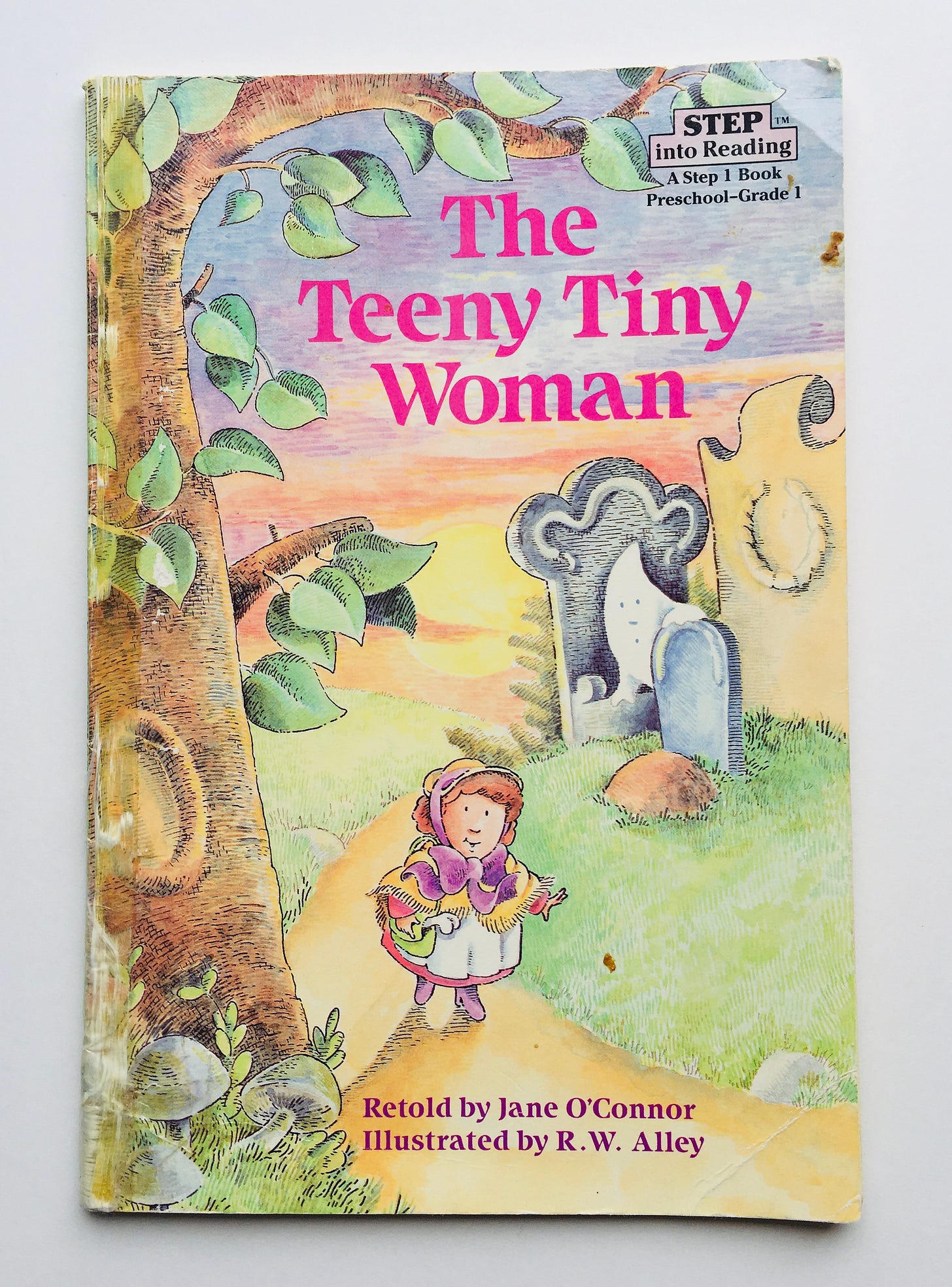

The Teeny-Tiny Woman by Jane O’Connor, illustrated by R.W. Alley (1986)

This is the first book I ever read entirely on my own — I mean literally, this is my childhood copy — but I don’t think I’m biased when it comes to this story. There are many versions of this old folktale (Paul Galdone’s is also quite good) but this is my favorite. A teeny tiny woman goes for a teeny tiny walk, picks up a teeny tiny bone from a graveyard, and decides to bring it home to make teeny tiny soup (don’t think too hard about the origin of the bone — I only noticed this as an adult, and ew). She brings the bone home and, too tired to make the soup, instead lies down for a nap. The original owner of the bone doesn’t like this, and makes it clear, through a serious of increasingly loud entreaties to the woman to “Give me my bone!” This is a timeless story, so don’t let the fact that it’s an early reader turn you off — the writing here is simple but solid, the illustrations adorable and not too scary (for those that may feel scared when the ghost shows up — I do a particularly spooky ghost voice, so at least one of my children is always a bit alarmed). This book is small in stature but not in fun.

We’re Different, We’re the Same by Bobby Jane Kates, illustrated by Joseph Mathieu (1992)

I am not and never have been a fan of character books — I think the vast majority of them are twaddle at best, terribly written, and make me want to scream, though Sesame Street is probably the most tolerable of the lot. This title is a glaring exception. It’s an excellent book about bodies — hair, eyes, noses, skin — which in and of itself is a worthy topic for toddlers and preschoolers, but this title succeeds where others of its kind don’t in its diversity. The representation here is important (I’m just going to keep repeating it over and over) and done very well, especially since there aren’t a huge number of books that directly address how we are different and how we are the same, especially for the little crowd. This book should be handed out at every pediatric appointment, displayed permanently in every library, given at every baby shower. It’s not absolutely perfect but it’s well-written, it’s an important title for a diverse children’s bookshelf, and most importantly, it has a beautiful spirit. It is a beautifully spirited book.

My Friends by Tarō Gomi (1989)

This is another book whose simplicity shouldn’t fool you: as the reader travels along with a little girl as she explains what she has learned from each of her animal friends, we learn something from her. Namely, that everything has wisdom and value, everything has something to teach us if we only pay attention — “I learned to march from my friend the rooster, I learned to nap from my friend the crocodile.” Gomi’s illustrations are, by now, classic and always enjoyable, but what I appreciate most about this title is how it de-centers humans and our experiences (that we tend to take as the most superior form of knowing) and realigns us with the proper order of things. In the end, the little girl comes back to the world we know a bit better — “I learned to read from my friends the books, I learned to study from my friends the teachers, I learned to play from my friends at school.” The repetition will appeal to little ones (and would be great practice for a emerging reader, especially if you or they are burned out on leveled readers, and who wouldn’t be) but I think there’s a deeper lesson here that’s valuable, if readers are willing to take the time to see it.

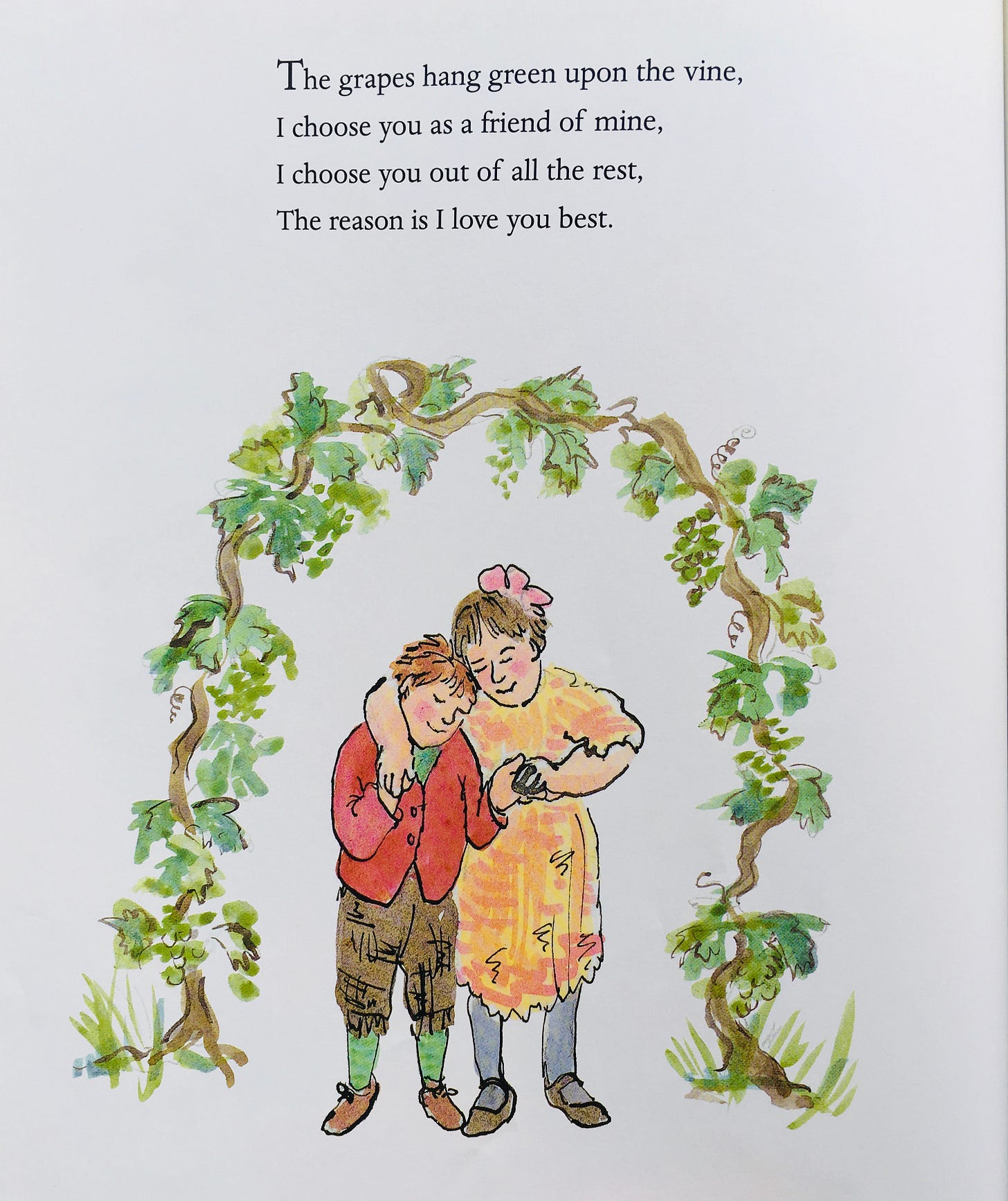

Some From the Moon, Some From the Sun: Poems and Songs for Everyone by Margot Zemach (2001)

“No truth, no poetry,” we said. A string of beautiful words is not poetry. It has to say something, something universal, a truth we all recognize. Robert Frost said a poem ‘begins in delight and ends in wisdom,’ and that’s what we think he meant. And it has to bring out that truth by both painting a picture and composing a song, just with words, and with the most economical number of words. A very, very, very difficult thing to do, which is why poetry is usually considered the highest form of written expression.” (Deconstructing Penguins: Parents, Kids, and the Bond of Reading by Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone)

I feel pretty strongly about poetry — in general, but especially for children. There are a million studies showing that poetry strengthens literacy skills, helps build memory and brain power, and teaches children not only to play with words but have fun with them. (This is anathema to the teach-to-the-test pedagogical culture that has been thrust upon education since No Child Left Behind, which is, in my opinion, exactly the reason to pursue it.) Beyond that, though, I think we need poetry, and I really mean need it, to make sense of our world, ourselves, and each other. Why on earth wouldn’t we share this tool with our children?

I have a decent collection of children’s poetry (much of which I plan to share here over time) but I chose to begin with this title because I am a hardcore fan of Margot Zemach. Her career spanned the 1960s-80s and there isn’t a single title that we don’t love (whether hers alone, or in collaboration with her husband, Harve; several have been published posthumously, which is why this one has a pub date of 2001). She is as gifted a storyteller as an illustrator, focusing often on adapted Yiddish and Eastern European folktales as well as sibling relationships (chiefly sisterhood, as she had four daughters). Some From the Moon, Some From the Sun: Poems and Songs for Everyone is a book of nursery rhymes, but don’t let that disguise its merits: not only are the poems here lesser-known than many classics (like, say, Hickory Dickory Dock or Baa, Baa, Black Sheep) Zemach’s illustrations are characteristically detailed, expressive, and warm. Reading this book is like sitting in the sun on a spring day when the grass has suddenly become green overnight. You know that day — satisfying for all ages, in the most welcome way.

Thanks for reading this week. Thanks for being here on the planet, enduring. As my 99-year-old grandma has told me at least monthly for years and years: this too shall pass.

Keep your head up and your spirit strong, in whatever ways you possibly can.