Hi there!

Thank you, thank you, thank you to those of you who took the time to take my survey last week 🙏 I’m already using your feedback to further hone some recent changes I’ve made and share more of my own experience and knowledge, at your request. To those of you who asked questions, look for my replies every few weeks in Notes from the Reading Nook, as well as new topics in my monthly issues of (How) Can we read?

I went back to my office last week, for one day, to try to remind myself what I like about being there, which I am happy to report actually worked (I like the skylight above my desk far more than I remembered — who knew it would be this simple thing?) I am going to return for a handful of days this week and next, an arrangement that is thus far an experiment in learning how to sleep a little less again, how to feed myself a real lunch, how to capture the firestorm of thoughts in my head that occur when I am commuting without putting myself or other drivers in danger (for years and years it has been dictating to Siri into OmniFocus but that system was a casualty of the pandemic and I have not yet found a replacement). In July I’ll be back amongst my fellow human knowledge workers 40 hours a week and, well, it feels weird and wonderful all at once — which is to say, it feels close to normal life, which is nothing if not weird and wonderful and full of constant uncertainties that make me uncomfortable and humble me again and again and also make said life the grand adventure it is.

A few years ago my best friend gave me an art print by Christina Persika that hangs right here in my home office just above my second screen so I can see it (while I am still here) peripherally all the time and focus on it specifically at least daily.

It reads:

We can be warriors. We can be soft and still have the strength to move mountains. We can feel things greatly and yet not be undone. We can be seen and heard and loved. We can be tender with each other and we can show up for one another. We are human and even with all of our broken pieces we are whole.

I have no idea where you’re at in terms of going back to the office, transitioning to whatever your work life looked like in the Before Times — I know some of you have probably never stopped being face-to-face (or mask-to-mask, as it were), some of you have already returned, some of you never will, some of you are doing a mixture of both (and some of you don’t work outside the home at all but are feeling Feelings too). What I wish for all of us as we live through the continuing changes of this once-in-a-lifetime event and the ceaseless change of plain old life is that we remember all of these things contained in this piece of art that I love, given to me by someone who knows me so damn well, but especially this one thing: we can choose to be tender with one another.

We have been through a lot.

Let’s be tender with one another.

Anna's Secret Friend by Yoriko Tsutsui, illustrated by Akiko Hayashi (1989)

If you are looking for a sweet title full of the perfect amount of mystery, look no further than this one: the story begins in media res, when Anna and her family are in the process of moving into a new house. There are boxes everywhere, and though Anna is happy to be living close to the mountains she is missing her old friends. In the midst of unpacking, just when she is beginning to feel bored and tired, she hears “a quiet tip tap sound” coming from the front door. When she goes to investigate, it’s not the postman she expects but rather a small bunch of violets dropped through the door — how did they get there, and who might have left them? The mystery mounts as the tapping happens repeatedly in the days to come and further gifts arrive — a bouquet of yellow flowers, an unsigned letter, a paper doll. Upon receipt of the last present Anna is quick enough to whip open the door, where she finds a little girl with bright red cheeks who wants to know if Anna wants to play (the answer is, of course, yes). This is a tender tale of a very specific kind of grief — the reader can see how difficult the move is for Anna and how the appearance of this little bit of magic in her life makes all the difference to her acceptance of her new life, and hope for the future — and the friendship that ends up being a balm. This is a quiet book, in some ways, but no less irresistible because of it.

(My library system, which usually has almost any out-of-print book I want, does not have this title so yours may not either — you can find it at a decent price on Thriftbooks — around $5 at the time of this writing — and for a little more on Amazon.)

Mole Music by David McPhail (1999)

If I’ve said it once I’ve said it a thousand times: I love, love, love David McPhail. I never tire of his books, it thrills me to find titles in his back catalog that are new to me, and I love sharing his lesser-known oldie-but-goodies, and that’s exactly what Mole Music is.

One day Mole happens to hear a violinist playing a concert on TV and he falls in love with the instrument, ordering one for himself and beginning what turns into years of practice, until eventually his talent surpasses the musician who originally inspired him. He imagines “that his music could reach into people’s hearts and melt away their anger and sadness. Why, maybe his music could even change the world!” but he also laughs at these thoughts of his, believing that no one has ever heard his music. Little does he know that his music has affected the world around him since the very beginning. In McPhail’s watercolor and ink illustrations Mole’s practice always takes place underground, at the bottom of the page, while the years pass above him, on the top half of the page. At first the only beings listening to Mole’s music are a tiny tree and a few birds, whose facial expressions make it clear Mole is a true beginner on the violin — but over time, the tree grows, and various people pass by and under the tree, which now has a line of musical notes running through it while Mole is playing. The reader sees how the people aboveground respond — George Washington and Abraham Lincoln make an understated appearance at one point — until eventually, a war begins and just as abruptly ends in peace when the opposing sides hear Mole’s music, and lay down their arms. No one aboveground ever knows where the music is coming from, and the text never once explains that Mole’s music actually is changing the world, making this a brilliant opportunity for conversation about (shoutout to Brené Brown) the story Mole is telling himself, the assumptions he’s making, the things we don’t see if we don’t look.

I love this book for many reasons — this double-story chief among them, but also for its quietude and the subtle but powerful message that practice for mastery takes a long time and a heart full of dedication, but dreams are real and they can change the world.

I Just Want to Say Goodnight by Rachel Isadora (2017)

I Just Want to Say Goodnight is a bedtime situation any parent can relate to: Lala’s father, just returned from a day of fishing, tells her it’s time for bed, but she insists she needs to say goodnight to all the animals around her before she can go inside.

“I just want to say goodnight to the fish!”

“I just want to say goodnight to the cat!”

“I just want to say goodnight to the bird!”

Toddlers and preschoolers will take especial delight in the repetitive nature of this story, as it speaks so clearly to their lived experience of stalling (or ways they wish they could stall, if tired and impatient parents don’t allow much of it, cough cough). Isadora’s oil paint and ink illustrations here are a departure from her work of the last 15 years, most notably the African-inspired cut-paper collage found in her various fairy tale adaptations, but I like it quite a bit: the rich, saturated images bring the African veld to life, and Isadora is particularly adept at conveying action and emotion through body language and facial expressions. When Lala finally does get into bed she must say goodnight to her book — the classic Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown — and this too feels familiar and relatable to parents and children alike. This is a simple, sweet book for a simple, sweet goodnight.

Roar of a Snore by Marsha Diane Arnold, illustrated by Pierre Pratt (2006)

“The sky was dark. The stars were bright. Each Huffle fast asleep that night.” Except for Jack, lying wide awake, who hears a noise he can’t account for: a roar of a snore. He gets up to investigate: is the snore coming from his hound dog, Old Blue? No. From his mother, Mama Gywn? No. From his sister, Sweet Baby Sue? No. No matter where he searches — adding a family member after ruling out each — the snore still roars. Finally the crew pinpoints the sound in the hayloft in the barn, where they clamber up together to find a teeny tiny kitten as the genesis of the roaring snore. This cumulative tale with truly terrific rollicking rhymes is a blast to read, with the perfect amount of suspense paired with expressive acrylic paint illustrations from Pratt. Along with The Seven Silly Eaters by Mary Ann Hoberman (which I reviewed in issue No. 25) and The Day the Goose Got Loose by Reeve Lindbergh (coming up next week), this is one of my favorite read-alouds to really lean into — the rhythm starts to roll and the whole book just takes off. Who tires of a book like that? Not us. I don’t think you will, either.

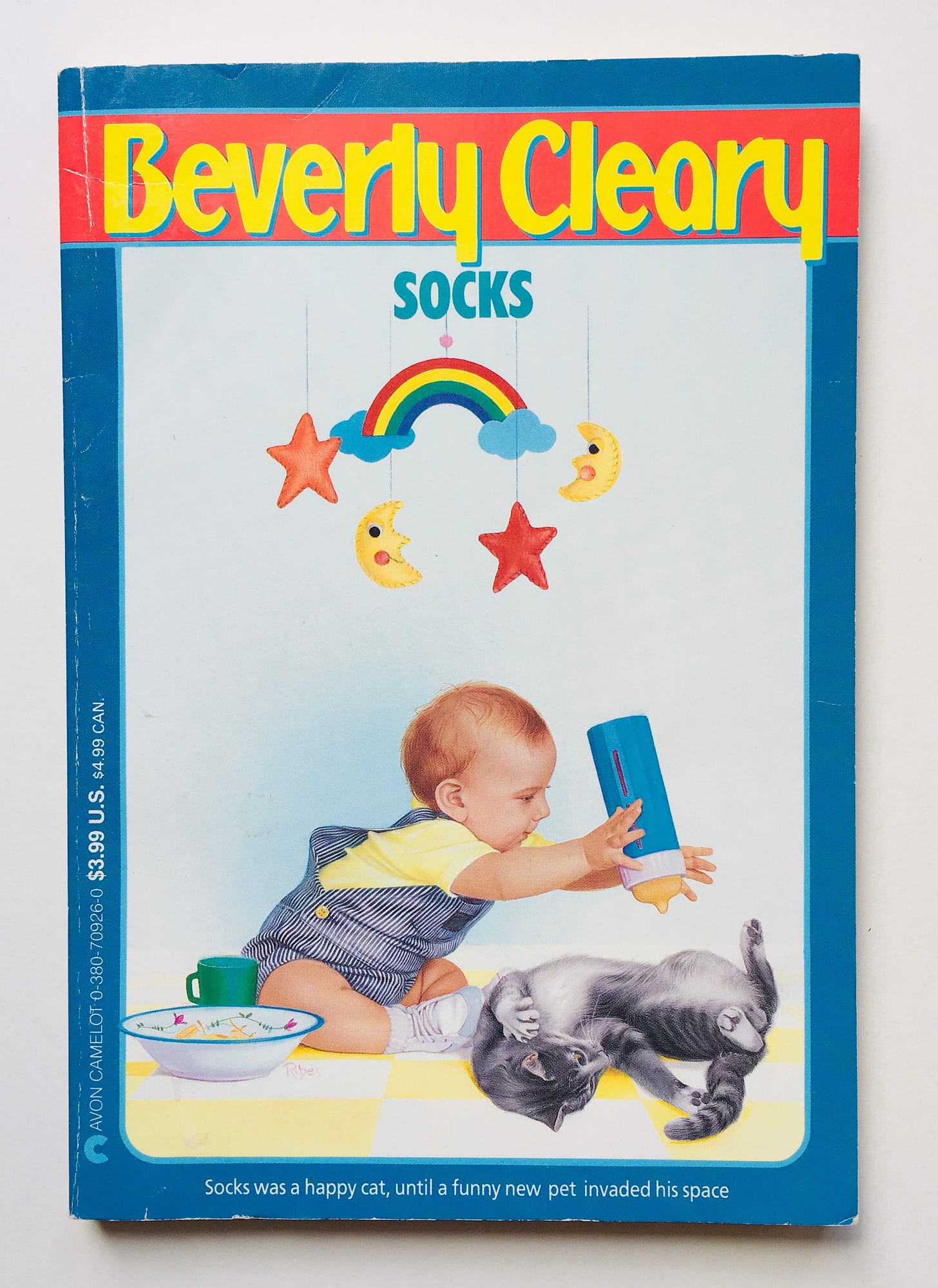

Socks by Beverly Cleary (1973)

I know it’s a little dumb to review a Beverly Cleary book, since she is not only ridiculously well-known but pretty much universally adored, except for the fact that when we listened to Socks on audio in the car as a family earlier this spring, my husband and I couldn’t stop laughing. I read Socks as a kid — I read everything Cleary ever wrote as a kid — and I remember liking it, though all I can truly recall is the tow-headed toddler on the cover of my edition (I had the 80s edition of all her books, which I still think have the best covers because I am and forever will be a child of the 80s):

In any case, what I learned from re-reading Socks is that it’s not only a good book, it’s a hilarious one at that. The story is straightforward: a couple named Mr. and Mrs. Bricker buy a kitten from two kids in the parking lot of a grocery store, bring the kitten home, name him Socks, and make him the happiest feline in the world until they decide to ruin everything — via every cat’s nightmare — by having a baby. The story is told by Socks himself and this is what makes it so brilliant: Cleary captures the essence of being a cat — the spirit of cat-hood, if you will — so astoundingly well it’s impossible to be a cat owner (or, more accurately, the servant and casual acquaintance of a cat that resides in your home) and not relate. When baby Charles William disrupts Socks’ life and chaos ensues chapter by chapter, Socks’ perpetual alarm, outrage, and disgust is dead-on — and so is the final outcome of the contentious relationship between the unassuming baby and the furious feline, which I won’t spoil for you, because you really should get this and read it out loud immediately — and it’s for this reason my husband and I laughed every five minutes while listening, and our kids loved it and have asked to listen again.

(Get this one from the library but if you enjoy it, buy it — your kids will welcome re-reading it when they’re older. I got myself a copy — the one pictured above even though it’s not nearly as awesome as my childhood edition — because 30-some-odd years later, it still totally delights me.)

(If you didn’t have a chance to take my survey last week, it’s not too late! You can do that here. You can also leave feedback and/or questions in the comments, or simply hit reply on this message.)

Thanks for reading today, good people.

Sarah

Wonderful essay, Sarah. And, yes: we can chose to be tender. I forwarded to my nieces, they’re loving your recommendations for their kids. Cheers!