Can we read? No. 16

Winning ugly

Real talk: I do not have my sh—stuff together for the Halloween special edition as I planned. I’ve dug the Halloween books out of their box (with glee — it’s my favorite holiday), I’ve sorted and chosen which ones to write about, but I haven’t even made it to taking photos. I am dog-paddling to keep my head above the water of my life at the moment, so today is just a normal issue…

Except that when I sat down to do a final edit and send this out across the light just now, 2/3 of this damn thing hadn’t saved. I HATE YOU, UNSTABLE INTERNET CONNECTION IN THE TIME OF CORONA. I give up.

But I’m here and I’m gonna win ugly and do it anyway today by just hitting send.

Halloween forthcoming. (I think. Hopefully. Maybe.)

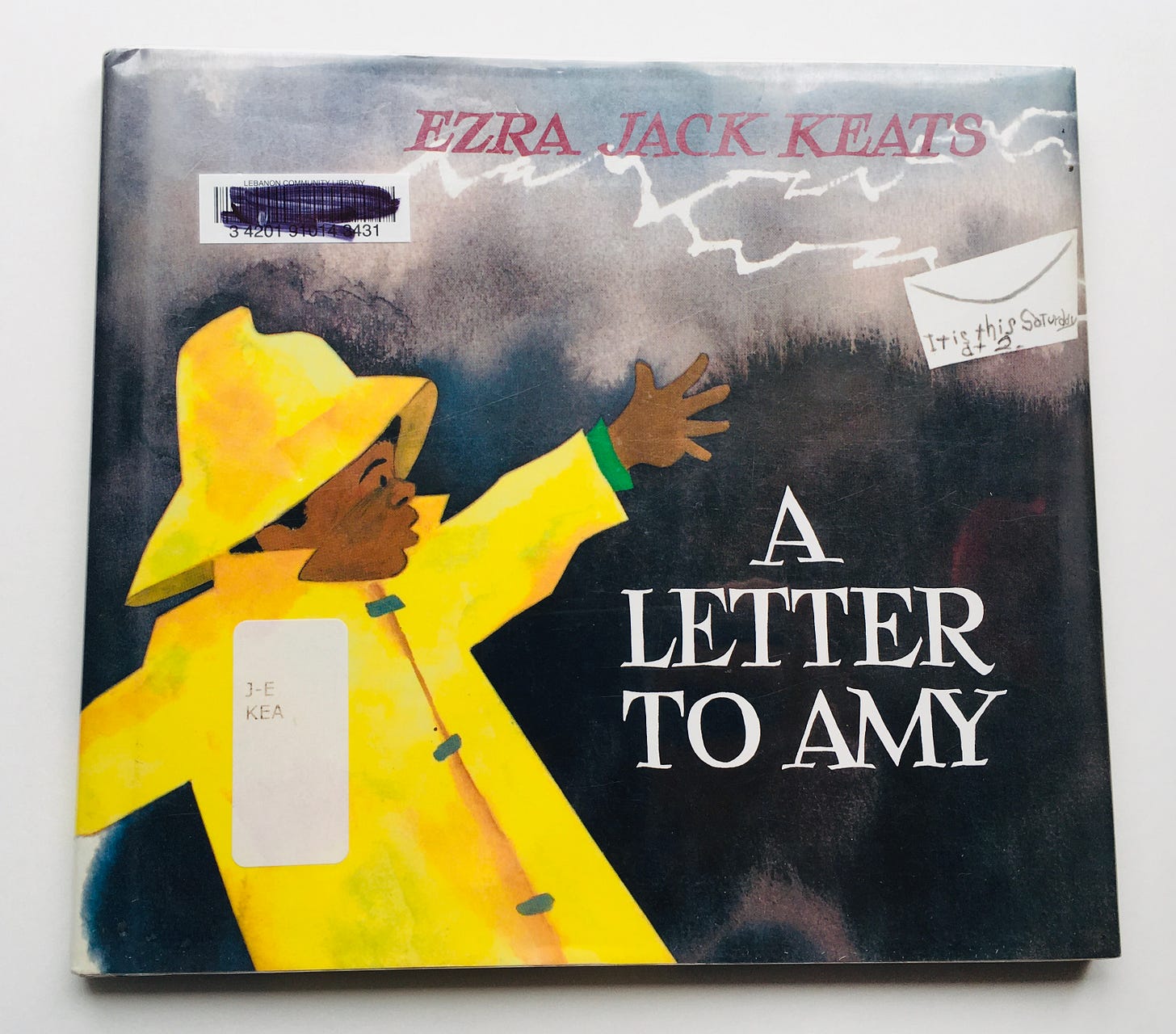

A Letter to Amy by Jack Ezra Keats (1968)

It’s probably unnecessary to feature a title by Keats (does anyone not know about his books?) but maybe you don’t! and in any case, I wanted to share this one because it makes me happy and hey, let’s all try to pay attention to things that make us happy right now, okay? In this title Peter, Keats’ recurring character and star, wants to invite his friend Amy to his birthday party. He prepares the invitation, but on his way to the mailbox, the wind whips the envelope out of his hand and in his haste to catch it, he crashes into none other than Amy herself, who runs away, upset. Peter’s feelings of sadness over hurting his friend (even if only slightly) are touching as he waits to see if she will actually attend his birthday party after their collision. On the special day, all his male friends arrive — but no Amy — until thankfully, there she is, and Peter’s birthday is everything he wanted it to be. Keats’ writing and illustrations are in his trademark style — you’ll never be disappointed by either (though some titles are better than others). The only downside here is that Peter’s friends take issue with his having invited a girl — I almost always change the language in that one section, not only because it feels dated, but because I’d rather have the focus be on the camaraderie of the birthday party and steadfastness of Amy’s friendship than the sexism of the moment. Everything else is upside.

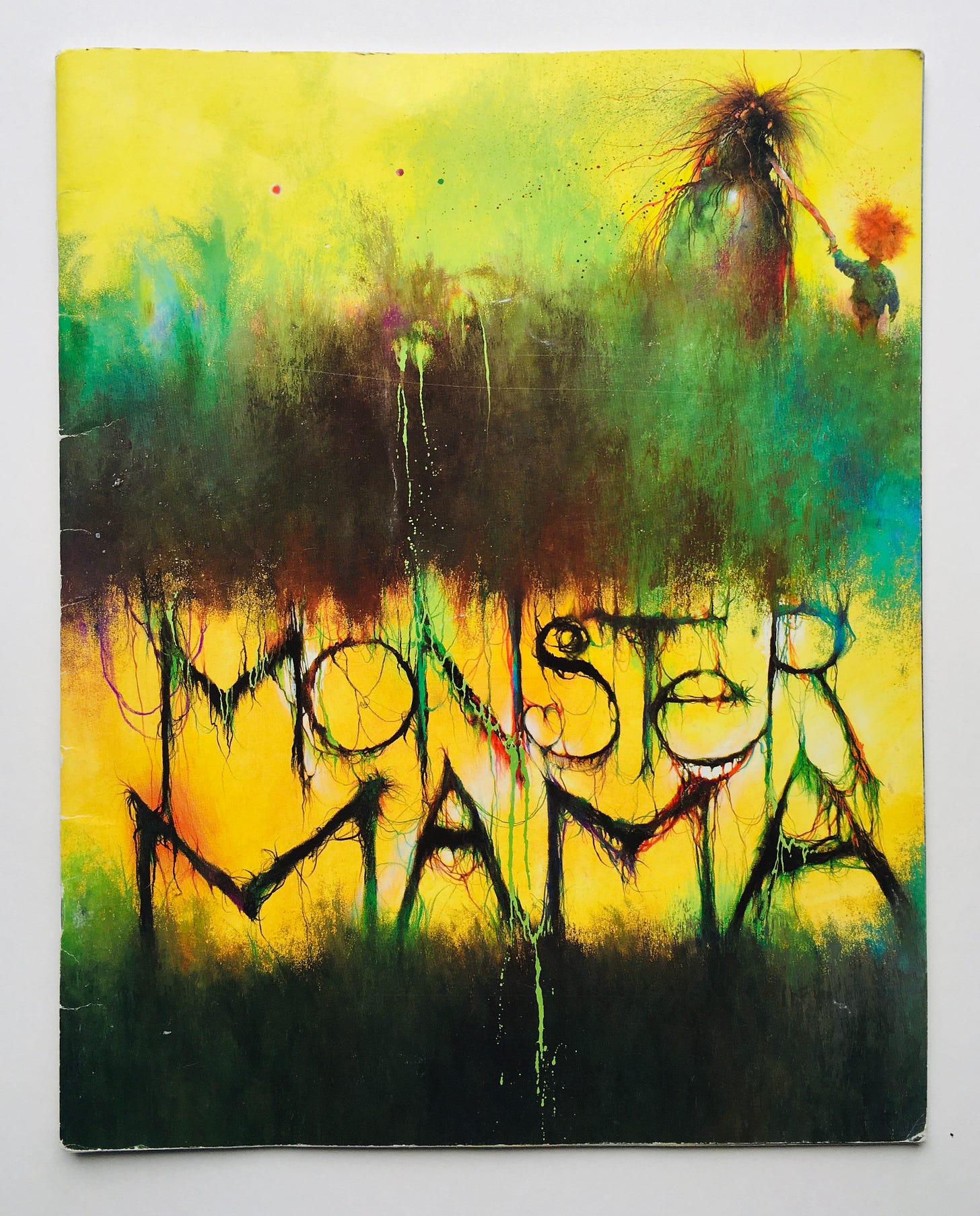

Monster Mama by Liz Rosenberg, illustrated by Stephen Gammell (1993)

I don’t know about you but I definitely feel like a monster mama sometimes, and my children would probably agree at least once in awhile. Maybe that’s why this has such appeal for kids and adults alike: there’s a bit of a monster in us all. In this story, Monster Mama’s insides aren’t nearly as bad as her outside, but nevertheless she shies away from the world — she covers herself with a cloak when she drops her son off at school when it’s raining, she hides when he has friends over. One day she sends him to the market to get strawberries for dessert, and as he is leaving after his purchase, he is teased and bullied and eventually tied to a tree by some other boys. That’s bad enough, but the coup de gráce comes when the bullies commit the cardinal sin of insulting someone: they talk trash about the boy’s mama. He snaps, just totally loses it (here we get to see his inner monster) until his mother comes upon all of them, and sets them straight with such confidence — and grace — that they’re all able to prepare dessert and share it together. What I love about this title is the unconditional love here, the message that not only are none of us perfect, we all have some pretty enormous character flaws — there are monstrous parts of us — and yet we are all still lovable and loved. That’s a message I need frequently. I mean, A LOT. I can imagine children do too.

Something From Nothing by Phoebe Gilman (1992)

While retellings of this Jewish folktale aren’t uncommon, this one is uncommonly good. (See also: Joseph Had a Little Overcoat by Simms Taback, which is slightly different, and absolutely delightful.) The jist of the story is this: a boy, or a man, has an item of clothing — maybe it’s a coat at first — that gets worn out, and so he turns it into something else, like a vest, and then that gets worn out, so he turns it into something else, like a tie, until the scrap of fabric is down to a button, and then finally down to nothing, and all that’s left is the story of the life of the fabric. It’s a cumulative tale (which are always remarkably popular with toddlers and preschoolers; I’m sure there’s some developmental reason for that) in general, but what makes this version stand out are the warm, vivid illustrations, and the fact that instead of the little boy making the fabric into something new each time, it’s his grandfather who does it for him, weaving in just that little extra bit of tenderness and care. There’s a coziness here, and a comfort — a sense that yes, you can always make something from nothing, especially if you have love.

Hickory by Palmer Brown (1978)

If a sweeter, dearer little book exists than Hickory, I haven’t yet found it. The story of a house mouse who lives in an old grandfather clock with his family, the title character ventures bravely out to live in the meadow in an old, half-buried pickle jar — there he meets both foe (a cat) and friend (a grasshopper named Hope, whom Hickory calls Hop for short) and lives a lively, but gentle sort of life. The first half of the book covers Hickory’s journey to the meadow — his family is entertaining — and the last half focuses on the friendship between the unlikely pair, not shying away from what will happen to Hop when the weather turns and the first frost comes. Brown’s illustrations are closer to etchings than anything else, and though this is a chapter book, with images on every page it’s more like a dense picture book and could be introduced to children as young as three and keep their attention (at least, this has been true in my home). Brown shows himself as talented a writer as illustrator — some lines are just breathtaking, his descriptions poetic and vivid, as in “A wedge of geese honked overhead…” — and since I am a person who believes ridiculously strongly in reading beautiful books to my children, this pleases me no end. This title reminds me more than a bit of Charlotte’s Web — though the theme of death is merely hinted at, rather than overtly experienced by the characters — and as such, the messages of acceptance and hope, grief and love exist side by side, together. As friends.

Thanks for reading. Take good care. 💛