Advice for the school year from two reading teachers

An interview with Meredith McNamara and Courtney Hanna-McNamara

I have zero memory of how I found Courtney Hanna-McNamara, though that’s not all that unusual — the circle of people I “know” to varying degrees online is deep, broad, old, and ever-widening.

When I searched my Gmail archives for Courtney’s name, that trusty digital record tells me I started receiving her lovely TinyLetter newsletter, Did I Miss Anything?, in 2018 — an idea based on a binder she used to keep in the corner of her classroom, where students could find everything they might have missed due to absence. Her notes, poems, word of the week, journal prompts, reading lists, opportunities for extra credit, and more delighted me for a long time (and still would, had she continued writing).

At some point last year, I saw an Instagram post of hers that mentioned her job as a literary interventionist, so — since I much prefer taking advice and gaining wisdom from people I deeply respect — when I came up with the idea of asking an educational professional for reading advice for the school year, Courtney came to mind.

When I asked her if she’d be willing to do an interview for my newsletter, she not only said yes — thrilling, because she has experience at the high school as well as elementary levels — she also mentioned that her sister-in-law, Meredith, is an elementary literacy specialist at a charter school in the Chicago area where they live.

Um, jackpot 🎰 Yes, please tell me — and thus, all of you — everything you know!

Meredith McNamara is an International Baccalaureate Primary Years Programme coordinator, instructional coach, reading specialist, and elementary classroom teacher.

Courtney Hanna-McNamara is a literacy interventionist, instructional coach, Suzuki violin instructor, and secondary classroom teacher.

Courtney explained the differences between their work: “Meredith is focused on helping students who are in the stage of ‘learning to read.’ My work centers on helping students — and the teachers of those students — who are struggling with ‘reading to learn.’”

Read on for more from them both.

What is literacy intervention?

Meredith: Literacy intervention is part of an overall educational approach known as MTSS, or “Multi-Tiered System of Support.” MTSS presumes that all kids learn differently and that targeted intervention specific to the needs of each child is the most responsive way to provide a student with what they need to flourish as a learner. The basic model is to think of a pyramid divided into three parts known as tiers, with Tier 1 as general full-classroom instruction that is intended to meet the needs of most learners. Without getting too into the weeds, literacy interventionists spend most of their time in Tier 2 and Tier 3 instruction, working with small groups of students to provide interventions specific to the literacy needs of those students.

Courtney: Literacy interventionists (or reading teachers, or literacy specialists — lots of different names for this job!) also provide instructional coaching support to classroom teachers so that they can better meet the needs of students within the Tier 1 full-classroom setting, whether teaching sample lessons or team-teaching or providing professional development opportunities for the whole staff. It’s a very collaborative, flexible role that can look different depending on what interventions are used within that school or district.

What are the greatest challenges children face when learning to read? When is it time to seek help?

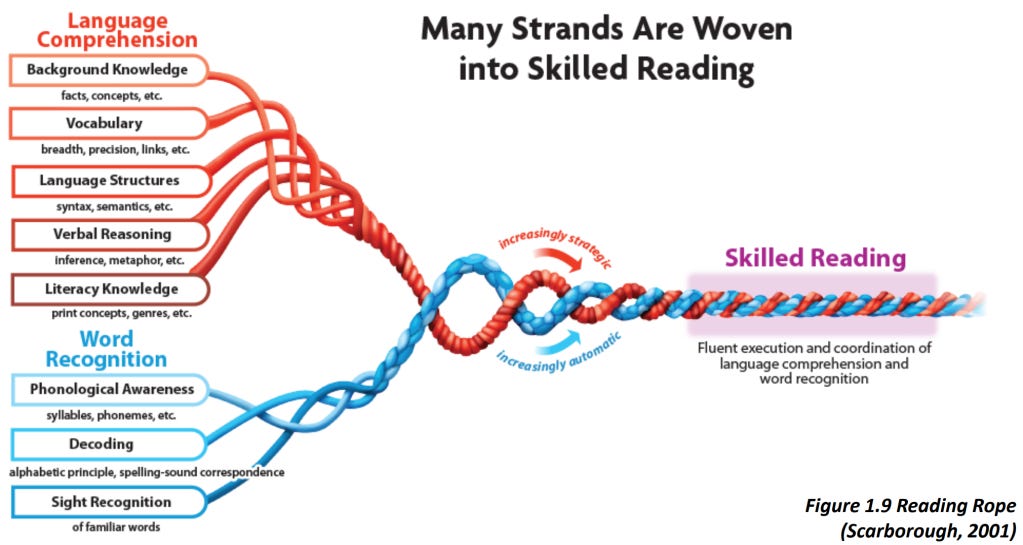

Meredith: Learning to read is unique from learning to walk or speak. It’s not instinctual. Each child will face different challenges depending on his or her learning style, how much support and opportunity for reading there is at home, and other factors. I like to use an illustration that’s called Scarborough’s Reading Rope with teachers I work with when we’re trying to figure out how to better support an individual reader who is struggling.

All of the strands weave together to create what we call skilled reading, including phonologic awareness and decoding (you might know this as phonics instruction), but also word recognition and background knowledge and vocabulary and verbal reasoning and more. A struggle or deficit within any of the strands can prevent the overall process of reading from clicking for that child; being aware of all of them and monitoring for difficulty and providing scaffolded support for the different strands is the best way to foster growth in reading.

Courtney: There’s a big push now to be reading by the end of kindergarten, but it’s actually really normal to still be learning to read later than that. Struggling to decode words and make meaning while reading starts to be more of a problem when it hasn’t all clicked by second grade. Second grade isn’t too late, though! There’s still so much that can be done at that stage that doesn’t require intensive intervention.

Meredith: Seeking help when you see that reading isn’t happening doesn’t necessarily mean looking for a reading tutor for your child.

Paying attention to what’s challenging for them and supporting them through that matters more.

Engage as a family, not by forced reading skill-drills that become a chore for your child, but by framing reading as shared time together. And don’t pull back because your child “doesn’t like reading!” They don’t like it…yet.

Read out loud and let them share the one word they know on the page. Read the same books over and over to practice fluency. Marvel over the illustrations. Talk about books together. Create opportunities to enjoy reading as a family.

What kind of reading materials do you find provide kids the most success?

Meredith: Any reading program or material that is billed as the solution to every kid’s reading challenges should give you pause! There’s no prescriptive answer to this.

What works is lots of practice, over time, with an attentive and caring adult who is noticing the particular struggles of that child and providing support and practice for those struggles.

Rich and varied materials matter the most.

Multiple modalities is really important, as is recognizing all of the strands of reading. Of course, if you suspect dyslexia or dysgraphia, more than this will be needed. I really think the Orton-Gillingham training for parents who are on this particular journey with their child can be life-changing, but it is expensive, though so is paying for individual tutoring.

Courtney: For my low readers at the high school level, they needed more time engaged in reading with some common stumbling blocks removed. I provided high-interest texts that I chose based on their individual preferences. I looked for reading material that had short chapters - some students balked at anything that felt long. Larger font size was a game changer for some. Pictures and illustrations instead of big blocks of text.

And above all, the regular opportunity to read, especially alongside other people they could talk about the book with.

How do you keep kids motivated to learn to read?

Meredith: Read together! When reading is a family activity that promotes togetherness, rather than a task to be accomplished, it’s enjoyable for everyone.

Let your children see you reading in your free time to emphasize how much you value it. They imitate us more than we care to admit, and choosing a book over scrolling social media will have a huge impact.

Read out loud, even for children at ages when you might think read-alouds seem too juvenile.

Choose rich, varied materials that they are personally interested in; visit your library together and make use of all of the resources available to you there.

Make reading an important part of your family’s routine.

What can parents and other caregivers do at home to support their growing readers — for children who are struggling as well as those who are not?

Courtney: Flooding your home with books, and making different books available regularly, is a great way to support your readers. The library is a great way to do this on a budget. Following book-related newsletters (like this one!) is a wonderful way to get ideas about books that might not have caught your eye. I’m always finding new title suggestions and requesting them through interlibrary loan, and I keep a list of special titles folded up in my wallet in case I happen to be at a bookstore or happen upon a great book sale somewhere.

One strategy I often use with my own children, and one that worked well with my struggling high school students, was to make lots of books available but not to directly encourage them to pick up a specific book. Sometimes children or students resist being told what to do even if it’s something they’d really enjoy, so leaving high-interest books around the house (even in the bathroom can work!) without any direct pressure from you can be enough to pique their interest.

My last strategy is not literacy-related but a strategy I use as a teacher and a parent often:

Let your children see you struggle to master something.

When we save our struggles for times when they aren’t around to witness them, our children get the impression that they are the only ones who make mistakes and face difficult obstacles to learning something new.

Be a beginner in front of your children whenever you can, and model a growth mindset for them to see and emulate. “I can’t do this…yet” or “This is hard, but I can do it if I practice” are two phrases that we use often around our house.

Learning to read takes time and patience, and children are more likely to be resilient in the process if they have a great role model!

An enormous thank you to Courtney and Meredith for taking the time to share their experience and expertise with us (and for their incredible patience as it took me, literally, 18 months to make it happen).

And thank you to you, too, for the commitment you’ve made to the children in your life to read to them, to help them become readers themselves, and to build a culture of literacy in your home, classroom, or otherwise.

Your ongoing effort matters.

Sarah

I love thinking about letting our kids see us begin to learn something. Such a great piece of advice!

As a parent whose young child was recently diagnosed with dyslexia, I REALLY hate the advice to just “read to your child” and “fill your house with books.” I am a librarian and my husband is a professor. We’ve been reading to our kid since day one. Yet she still struggles. A little more empathy and acknowledgment for parents trying their best would have been nice in this piece...